- In 1871, President Ulysses S. Grant worked to acquire the Dominican Republic.

- Grant had concerns over the long-term future of newly-emancipated Black Americans and how they would co-exist with white Southerners.

- Historians told Insider they believe this story can inform the wider conversation around Puerto Rico's statehood.

As calls grow louder to decolonize Puerto Rico, its territorial status serves as a reminder of the United States' not-so-distant colonial past.

Before Puerto Rico was annexed by the United States in 1898 during the Spanish-American War, the US had made attempts to annex other territories in Latin America, including Cuba and the Dominican Republic.

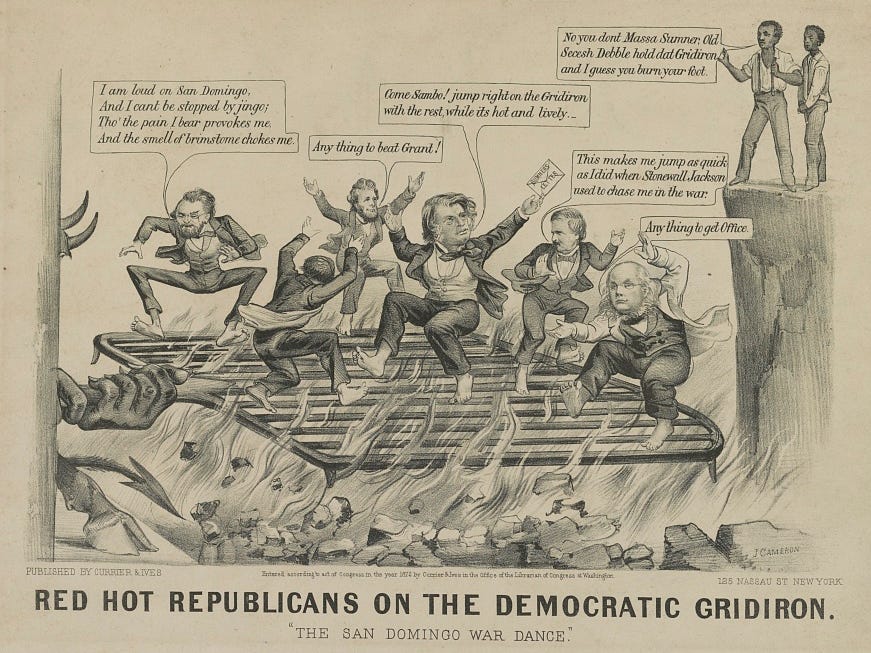

On June 30, 1871, a bill titled the Annexation of Santo Domingo failed in the US Senate by only 8 votes. If passed, the country would have moved to acquire the Dominican Republic and make it a state.

The political climate of the United States beginning in the late 1860s was ripe with questions about what was next for Black Americans. Historians told Insider that in the early 1860s, before the end of the Civil War, politicians in Washington, D.C. were concerned with how white people would treat newly-emancipated Black Americans. One of the ideas that some politicians considered was urging Black Americans to move away from the mainland entirely.

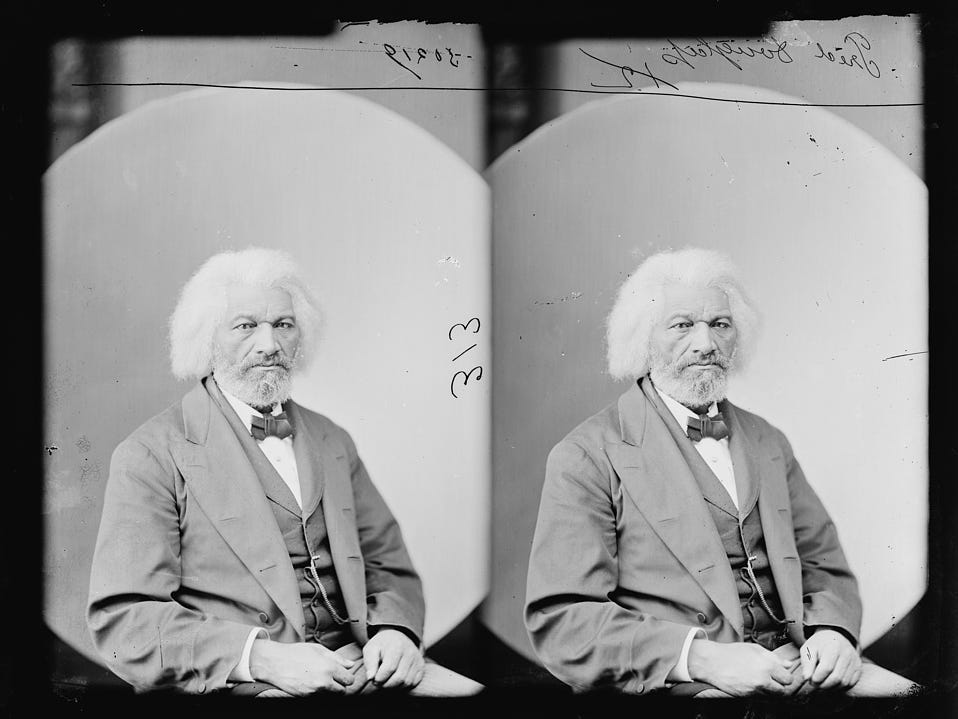

Some politicians and activists, including Frederick Douglass, supported efforts to annex Santo Domingo (now, the Dominican Republic), as they saw it as a place where Black Americans could own property and live freely. Douglass saw it as an opportunity to grow the Black American population. Other politicians also had an expansionist mindset for the US.

Upon hearing about the US' desire to expand, leaders of the Dominican Republic reached out to make a deal.

"I think it's kind of a really telling moment in US history, in terms of how people thought not only about African Americans but also how they thought about Blacks in the diaspora," Dr. Lauren Hammond, Associate Professor of History at Augusta College told Insider. "You could kind of use it almost as a comparative case and raise questions about Puerto Rico's status and statehood."

Ulysses S. Grant said the biggest conflict in the US was a "prejudice to color"

A few years after the Civil War, it was becoming clear to those in Washington that Reconstruction efforts in the former Confederate-controlled Southern states were failing. President Ulysses S. Grant grew worried about the long-term future of Black Americans.

Drawing on prior conversations in Washington, Grant came up with a solution. According to a memo, he wrote that "prejudice to color" was the biggest conflict in the country and a solution to this would be moving Black Americans to the island.

Grant wrote, "Caste has no foothold in Santo Domingo. It is capable of supporting the entire colored population of the United States, should it choose to emigrate … The colored man cannot be spared until his place is supplied, but with a refuge like San Domingo, his worth here would soon be discovered."

Despite being the last known American president to own an enslaved person, Grant grew up in an abolitionist household, and, as a Union general, fought alongside Black soldiers, which may have impacted his views on slavery. Grant was not the first US politician who considered sending freed Black people outside the mainland. Afraid that Black and white Americans could not peacefully co-exist, President Abraham Lincoln had also proposed sending emancipated Black people to Liberia or Central America.

Hammond told Insider that while Grant was concerned with the racism facing Black Americans, he was also an expansionist who believed in the Monroe Doctrine, a policy from 1823 that urged European powers not to interfere in the Western Hemisphere. Grant was initially interested in acquiring Cuba, a Spanish territory, but once that was not realistic without war, he turned his interest to the Dominican Republic.

While historians told Insider that there is evidence that the US also considered annexing Panama or Brazil at the same time to serve the same purpose, Dr. Gerald Horne, a historian who holds the Moores Professorship of History and African American Studies at the University of Houston, told Insider that quickly fell through because those countries were skeptical about why the US would send only their Black population there.

"There was less concern in the Dominican Republic than in other Latin American nations about accepting what was considered to be a 'Trojan horse,'" Horne, the author of "Confronting Black Jacobins," which details the history of the Dominican Republic, told Insider.

Leaders of the Dominican Republic wanted the US to annex the island, historian said

After the War of Restoration against Spain, the Dominican Republic was looking for protection, Hammond said. They were in deep debt and susceptible to being reconquered by Spain, so President Buenaventura Báez reached out to the United States.

Báez was aware that President Grant was looking to acquire territories off the mainland, so he asked if the Dominican Republic could be annexed.

On February 16, 1870, a vote was held in the Dominican Republic; 15,695 residents voted for annexation, and only 11 voted against. With over 99% of the vote, a referendum passed in the Dominican Republic.

Hammond said she doesn't trust the results of that vote.

"There ended up being threats from Buenaventura Báez," Hammond told Insider. "So it's actually very difficult to get a true pulse on what was happening in the Dominican Republic."

In the US Senate, the annexation bill to acquire the DR failed 28-28 on June 30, 1871. It needed ⅔, or 66%, of the vote to pass.

Much of the opposition to the bill was led by Massachusetts Senator Charles Sumner. Grant spent many months trying to get Sumner on board, but Sumner had one main sticking point.

Sumner did not believe that the United States should acquire any territories in the Caribbean or Latin America. Dr. Nicholas Guyatt, professor of North American history at the University of Cambridge, told Insider that's because Sumner believed that warmer climate areas belonged specifically to Black people.

"He gave these speeches about race-blind citizenship, but then he also said specifically on this question that the tropical zone belongs to Black people," Guyatt told Insider. "If you say that then what are you saying about other areas, like the subtropical regions of the US."

Guyatt also said that, given conversations and speeches in DC at the time, he believes that the US would have granted the Dominican Republic statehood had the annexation vote gone through. Many politicians stressed the point that the US couldn't be like other empires with unincorporated colonies. However, a few decades later the country's position had changed.

"Had [annexation] happened, I think it would have created a new dynamic within the federal system, which would have made the conquest of 1898 very difficult to hold onto these territories like Puerto Rico for a long period of time," Guyatt told Insider.

Most white Southerners didn't support annexation, historian said

During this time, white Americans largely fell into three groups concerning the issue of annexation, Dr. Horne told Insider. One group supported removing Black Americans from the mainland to remove any reminders of slavery. Another group supported removing Black Americans because they didn't want the US to become a multiracial republic. And a third group wanted to keep Black people on the mainland because they were a cheap labor supply.

In the South, Hammond said the main sentiment was against annexation because many Southerners were uncomfortable with more non-white people joining the US. There were also whispers that if the US annexed the Dominican Republic then it wouldn't stop there. Some were afraid they would soon take the entire island, including Haiti.

"Once slavery was over, that fear of including additional Black people and those additional Black people perhaps being given rights and treated as equal US citizens was deeply distasteful and disturbing to the vast majority of Southern Democrats," Hammond said.

Overall, Hammond and Horne said the bill failed because it did not have broad support outside Grant's circle.

Frederick Douglass' judgment was "clouded" when it came to annexation, historian said

A complex part of this story is Frederick Douglass' role in the country's desire to acquire the Dominican Republic.

After the bill failed in the Senate, President Grant asked Congress to approve a three-person commission to go to Santo Domingo. The goal of the commission, according to Grant, was to go on a "fact-finding mission," to see if Dominicans supported becoming a part of the US.

Frederick Douglass was one of the three assigned to the commission.

"My selection to visit Santo Domingo with the commission sent thither was another point indicating the difference between the old time and new," Douglass said after his selection.

Douglass' understanding of why the US was annexing Santo Domingo seemed a bit misguided, historians told Insider. According to the Chicago Tribune, during a speech in December 1871, Douglass said that the US was annexing Santo Domingo through "native consent," rather than "intervention."

However, Horne said that historians have long struggled with how to tell this part of Douglass' story.

Douglass was born a slave, became free, and was a key abolitionist who advised former President Abraham Lincoln on the ills of slavery. Douglass also had an understanding of European colonialism in the western hemisphere and supported independence efforts. However, some historians say he failed to understand the nature of conquest and colonialism when it came to the United States. Douglass also didn't understand the US' domestic motivations for acquiring the Dominican Republic, such as sending Black Americans to the island.

"This was not Fredrick Douglass' finest hour," Horne told Insider. "Many were just so grateful, so gratified by being free of slavery. And I think it sort of clouds the thinking. They were willing to go along with any plan Washington came up with."

Hammond said she reads Douglass' statements from that time through a slightly different lens. Hammond believes Douglass was seeing the annexation of the Dominican Republic as a win for Black Americans. They would be able to add voters to the Black electorate and thereby increase the chances of gaining civil rights for Black Americans.

"I think one thing we have to remember is that Frederick Douglass was living in a very complicated time and was a super complicated individual," Hammond told Insider.