- In 1863, Abraham Lincoln enacted a plan to resettle 453 freed Black Americans to a Haitian island.

- Lincoln viewed colonization as a way to free Black Americans — but keep them apart from white society.

- The experiment ended in disaster, putting an end to plans for colonization.

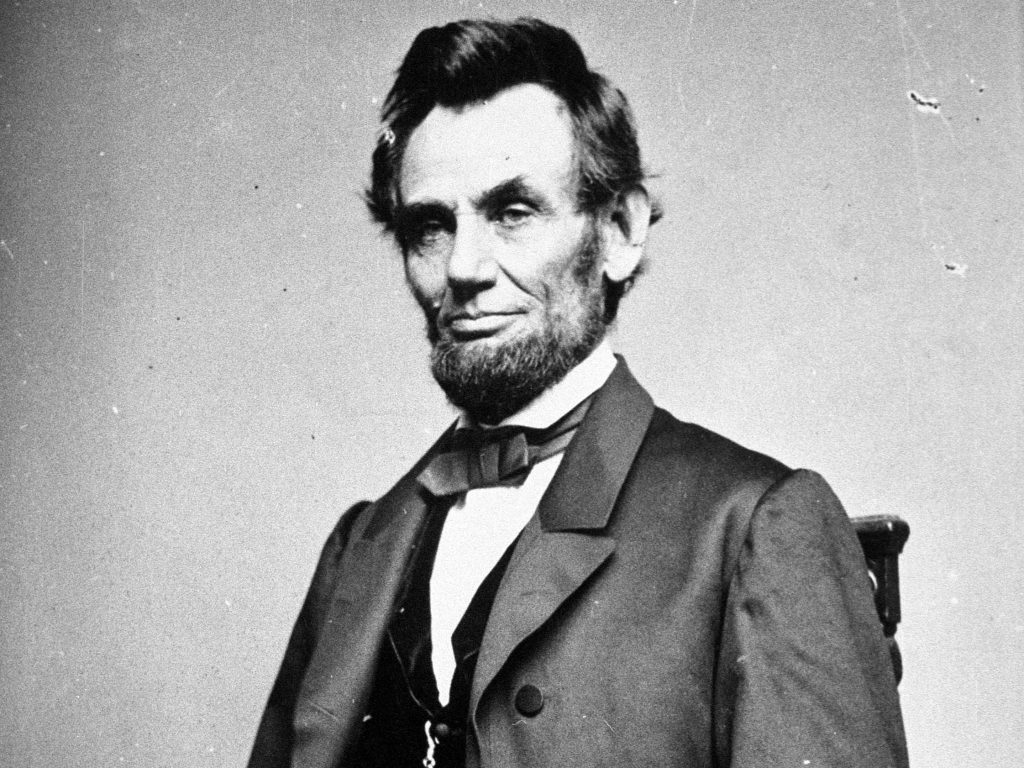

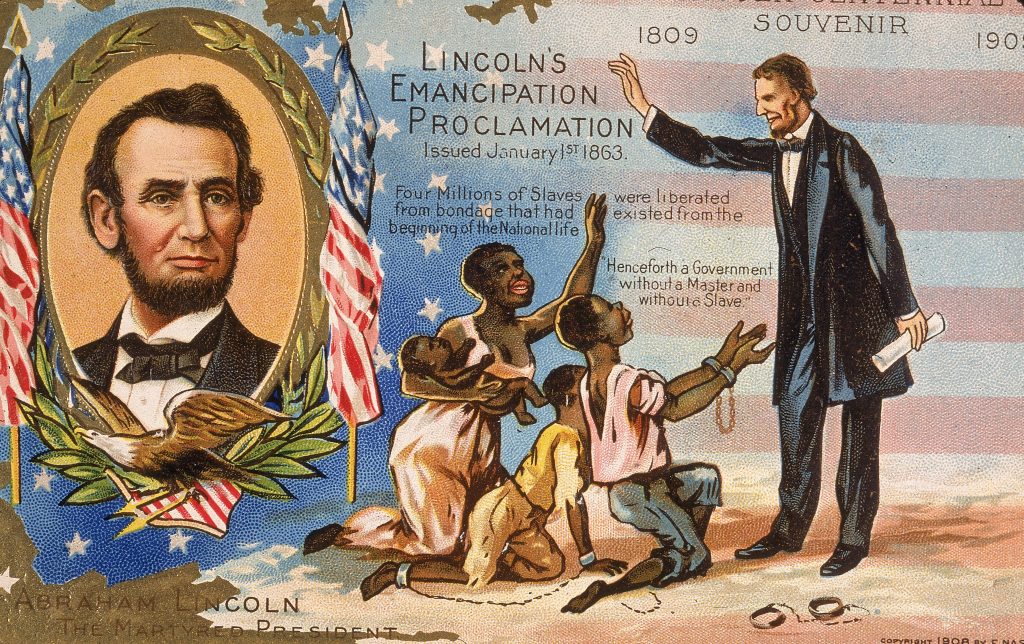

On New Year's Eve 1862, a day before he issued the Emancipation Proclamation to end slavery in America, President Abraham Lincoln signed a contract agreeing to relocate 5,000 free Black Americans to the Caribbean.

Lincoln had long been a staunch supporter of colonization, the state-sponsored emigration and resettlement of freed Black Americans outside America. Colonization was widely supported throughout the antebellum United States for religious, economic, and social reasons. Lincoln saw it as a remedy for emancipated Black Americans, expressing hope that they would find justice "in restoring a captive people to their long-lost father-land, with bright prospects for the future."

Colonization was also seen by some politicians as a pragmatic solution for a country still embroiled in a civil war: It would satisfy those in the Confederate South who opposed emancipation and living alongside freed Black Americans.

In his second annual message to Congress on December 1, 1862, Lincoln summoned the Union to abolish slavery and proposed a constitutional amendment to colonize Black Americans outside the US. He sought plans to realize this vision, and received ones that would establish colonies of emancipated Black people in countries like New Granada and Liberia.

When he heard about a plan for a colony on Île à Vache ("Cow Island"), a small island off the coast of Haiti, Lincoln was intrigued. But he had little idea that the endeavor would not only fail catastrophically — leading to the deaths of more than 100 freed Black Americans — but also snuff out his lifelong dream of colonization.

The Île à Vache plan was the brainchild of a cotton planter

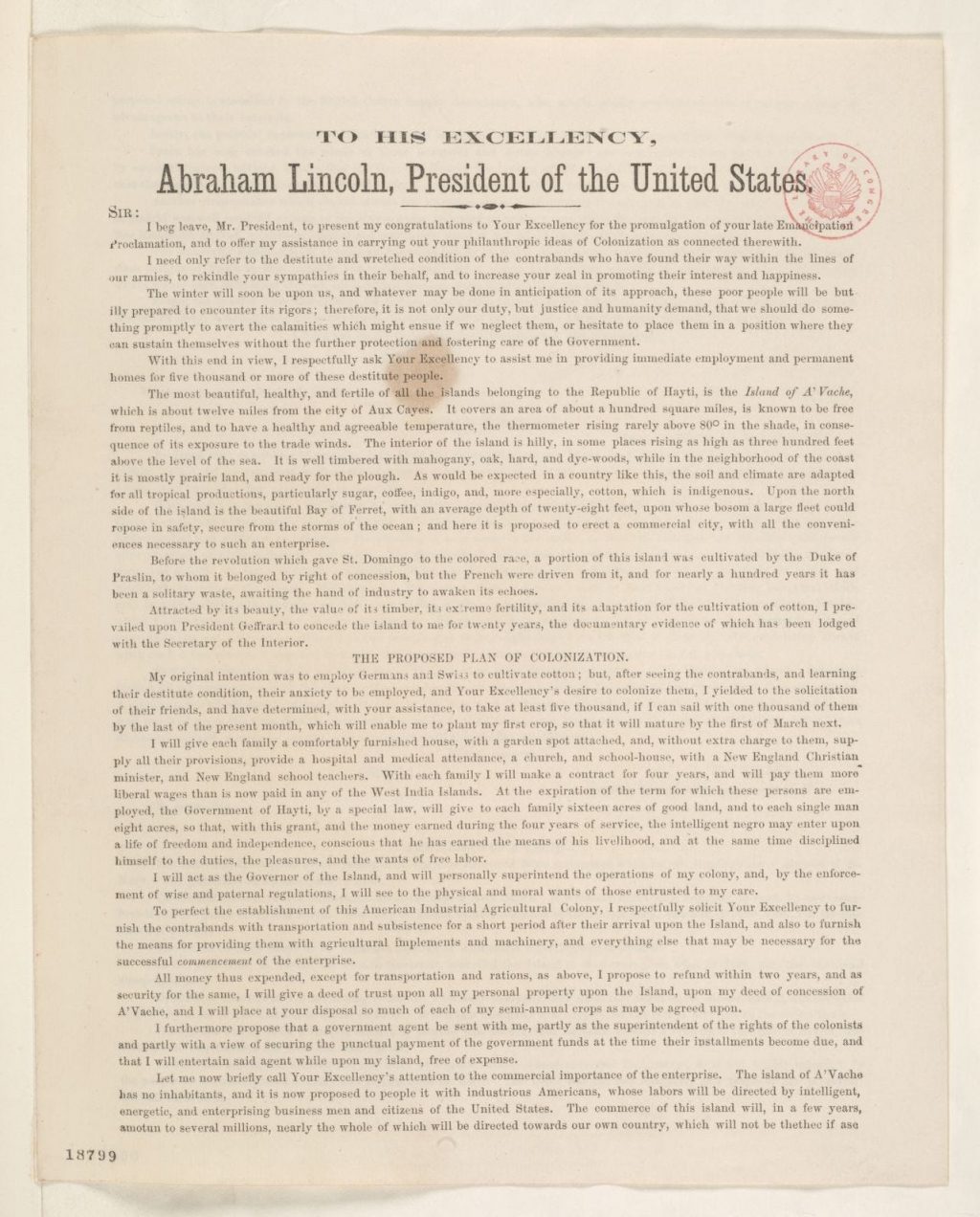

Bernard Kock, an entrepreneur and Florida cotton plantation owner, spied a business opportunity when he visited the 1862 World Fair in London. Impressed by the quality of cotton he saw at the fair, Kock conceived a plan to develop Île à Vache into a cotton farm by sending newly emancipated Black Americans there.

Each family would receive homes, access to hospitals and schools, and be given 16 acres of land and their wages after the completion of four-year work contracts, according to Kock's plan.

One month before he signed the Emancipation Proclamation, Lincoln agreed to terms with Kock, which included $600,000 in funds authorized by Congress. Colonization would ultimately be voluntary for those who resettled, but it was strongly encouraged by Lincoln, Kock, and other supporters. Plans for the first government-run colonization were set in motion.

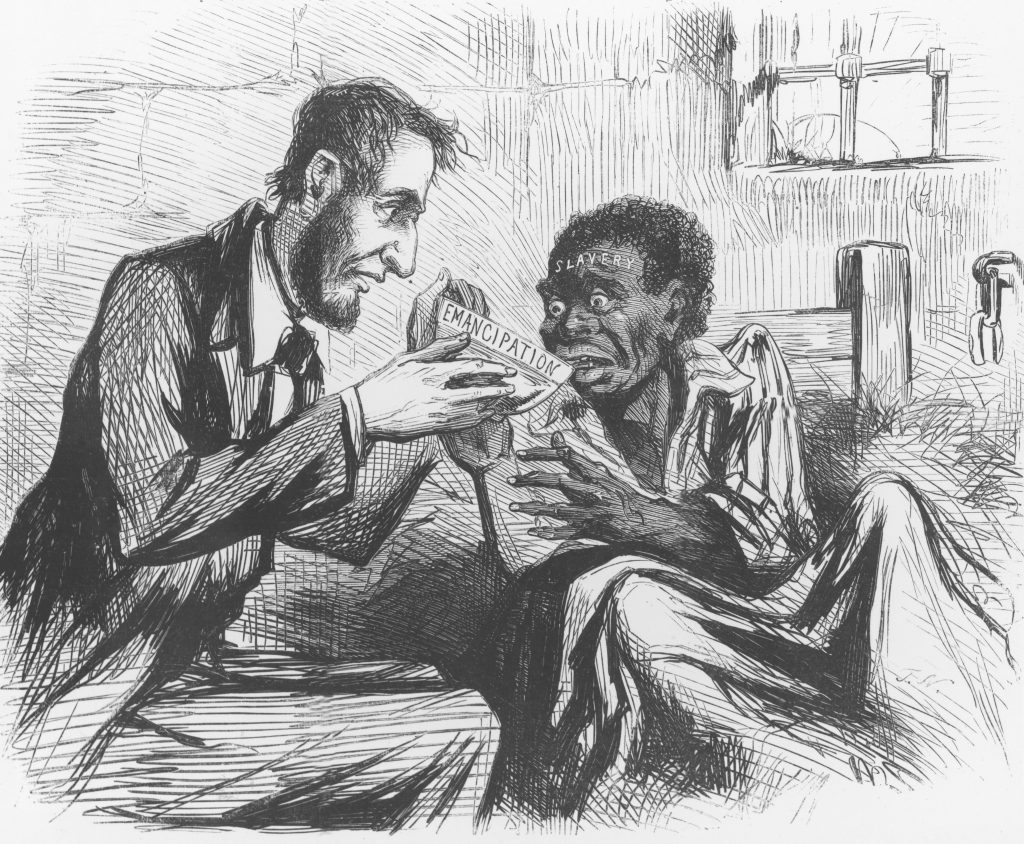

Black and white abolitionists opposed colonization

Lincoln's proposals for colonization faced major opposition from Black and white abolitionist groups.

"Shame upon the guilty wretches that dare propose, and all that countenance such a proposition," Frederick Douglass wrote in his newspaper "The North Star" in 1849. "We live here — have lived here — have a right to live here, and mean to live here."

William Loyd Garrison, a prominent white abolitionist and journalist, denounced the plans as "puerile, absurd, illogical, impertinent, and untimely."

Animosity reached a fever pitch on August 14, 1862, when Lincoln met with a committee of five Black leaders at the White House.

"You and we are different races. We have between us a broader difference than exists between almost any other two races," Lincoln told them, only sparking further outcry and rebuke from opponents.

The Île à Vache experiment quickly proved to be disastrous

There were early red flags with the Île à Vache endeavor. An investigation into Kock in early January suggested he'd used deceptive business practices in prior ventures. The US Commissioner in Haiti also told the Lincoln administration that Kock was an unpopular figure in Port-au-Prince, and that he hadn't heard of any progress in constructing the settlement.

Lincoln formally rescinded Kock's contract on April 16, 1863, but it was too late.

Two days earlier on April 14, more than 450 Black settlers boarded a ship to Île à Vache, excited to leave former Confederate territory for what they had been told would be a better life.

But disaster struck swiftly: A bout of smallpox killed at least 25 settlers at sea. When they arrived on the island, they found no reasonable shelter and had to construct crude huts. Kock, who became the overseer of the island, instituted a strict "no work, no rations" policy that echoed the antebellum era. Disease and starvation quickly followed.

The settlers mutinied three months later, and Kock fled the island while the Haitian government dispatched military to maintain order.

Finally on February 1, 1864, amid escalating media reports that railed against the project, Lincoln ordered for a naval vessel to rescue the settlers. A month later, a ship carried the 350 surviving emigrants back to America.

The failed experiment had lasting effects on America

The disastrous Île à Vache experiment ultimately put an end to Lincoln's strident advocacy of colonization — one of the Great Emancipator's more controversial legacies.

"I am glad the President has sloughed off that idea of colonization. I have always thought it a hideous & barbarous humbug," John Hay, Lincoln's personal secretary, wrote in his diary.

While Île à Vache was a disastrous failure that led to the deaths of more than 100 freed African Americans, some historians see it as a pivotal moment for American history. After the experiment, Lincoln abandoned his quest for colonization and instead embraced policies of Black inclusion and assimilation.

"The incident on Île à Vache, while undeniably a tragic and preventable event, proved a retrievable mistake through the negation of an unfeasible and unpopular solution to racial questions, replaced by subsequent transformation toward a more integrated future," Graham Welch, a historian and attorney, wrote.