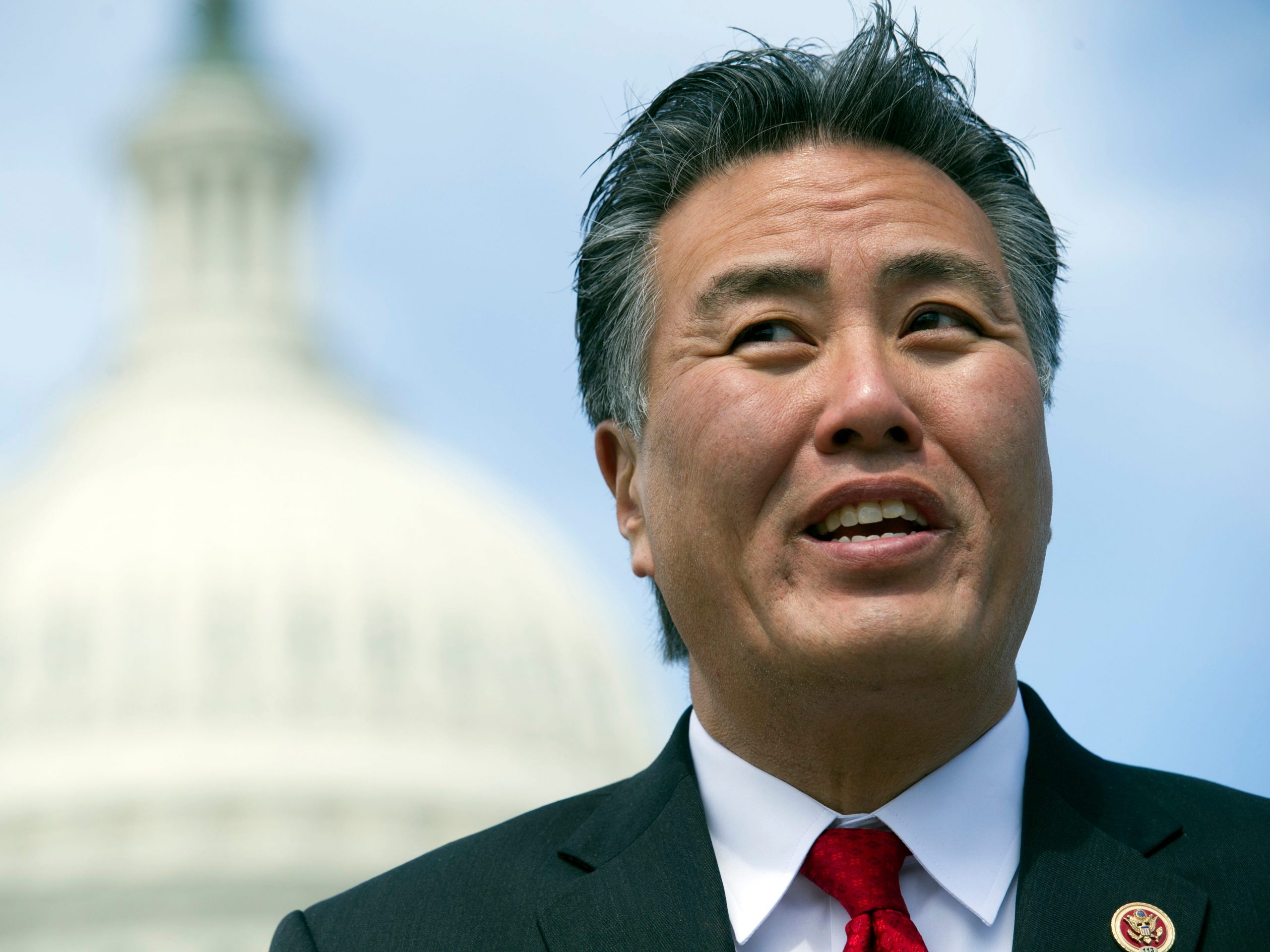

AP Photo/Cliff Owen

- A four-day week is more likely to mean a cut in overall hours, rather than a reduction in days.

- There are many ways it can work, said Rachel Statham, a senior researcher from the IPPR think tank.

- Trials from Iceland and a newly published report from Scotland offer a potential blueprint.

- See more stories on Insider's business page.

When Mark Takano, the democratic representative for California's 41st district, introduced his 32 Hour Work Act to Congress in August 2021, he used Twitter to announce it.

"BIG NEWS: I've just introduced legislation in Congress calling for a four-day work week," his tweet read. "It's well past time that Americans have more time to live their lives, and not just work."

But is Takano's vision for a four-day week likely to become reality?

Often when people like Takano are talking about the concept, they're talking about a more general reduction in working hours, without a general loss of pay.

The general term "four-day week" is a misnomer, as Insider previously reported. In large part, it's a marketing banner.

The proposed legislation aims to cut the standard working week to 32 hours, by reducing the 40-hour threshold at which workers qualify for overtime pay. Takano said this would result in a 10% pay increase.

The vision of enlivened, usually young, wealthy tech workers, clocking off on a Thursday for a long weekend is one narrow version of it. But the reality for many is going to look very different.

Take a couple of well-publicized trials from Iceland. The trials have been widely hailed as an "overwhelming success" for the concept of the four-day week. However, the majority of the reductions seen were to do with working hours, rather than a shift towards reducing days in the office.

In one trial, care staff, local government employees and service-center workers cut their weekly hours from 35 to 40. The other saw civil servants, across a variety of shift patterns, cut their hours.

"A shorter working week isn't always a shift from working a Monday to Friday pattern to full-time Monday to Thursday pattern, it might be a more gradual process," said Rachel Statham, senior research fellow at the think tank Institute for Public Policy Research Scotland.

"You can't increase productivity in social care to the extent that you don't need a carer to come in on a Friday anymore," Statham said.

Scotland became the latest government to announce support for the four-day week. It has set aside £10 million in order to fund trials.

Like Takano's bill, Scotland's experiment is in its early stages. Statham is the lead author of a report published this week calling for the funds to be used on trials investigating the effects on different roles and sectors.

She said it's important to make the distinction because the idea of reduced working hours needs to work for every level of the economy - rather than a shift that happens exclusively among those who already have high levels of job security. These include the tech employees and knowledge workers.

Otherwise, trials could reinforce inequalities that already exist within society. Low-income workers in Scotland for example are often pushed into working excessively long hours due to a lack of job security.

Statham highlights increased annual leave entitlement, offering longer parental leave, even increasing sabbatical rights, as some of the "policy levers" that could lead to a working time reduction, more generally.

While it might not lead to the universal notion of everybody having an extra day off, any type of reduction in working hours is an important step in improving work-life balance.

"For business to get to a point where it's a three-day weekend requires quite a change to the way we structure our society," said Charlotte Lockhart, CEO of 4 Day Week Global, a consultancy and campaign group.

"But with any of these conversations, it's about getting the idea up first, and then having that as being part of the conversation that ultimately leads to change," she added.