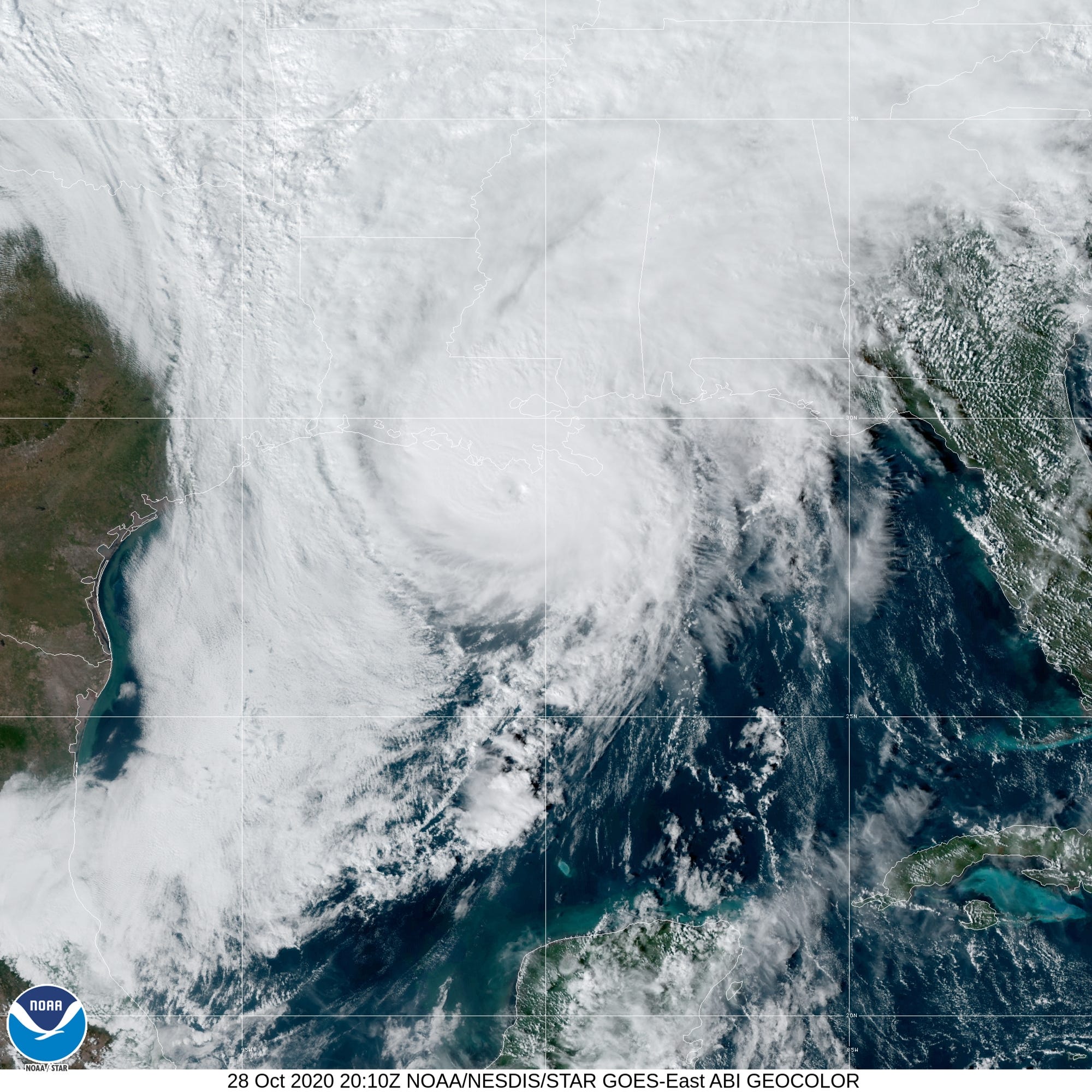

NASA/NOAA

- As of Thursday morning, Tropical Storm Zeta was in northeastern Alabama, approaching the Georgia border, according to the National Hurricane Center.

- The storm is expected to weaken some more on Thursday, while hurricane and storm surge warnings called off for the Mississippi coast and Florida panhandle, Reuters reported.

- Zeta made landfall west of Grand Isle, Louisiana, on Wednesday around 5 p.m. local time with winds of 110 mph — just 1 mph short of being a major Category 3 storm.

- The storm has left at least two people dead, according to NBC News. Parts of the Florida panhandle have also closed voting sites early due to tropical storm warnings.

- Zeta is the 27th named storm in the 2020 Atlantic hurricane season, the second-highest total on record.

- Visit Insider’s homepage for more stories.

Hurricane Zeta weakened to a tropical storm overnight, hours after striking Louisiana as a Category 2 storm and leaving at least two people dead.

As of 5 a.m. EDT, Tropical Storm Zeta was in northeastern Alabama, approaching the Georgia border, according to the US National Hurricane Center.

It was moving northeast at 39 mph, with maximum sustained winds of 60 mph.

According to Reuters, the storm is expected to weaken some more on Thursday, and hurricane and storm surge warnings have been called off for the Mississippi coast and Florida panhandle.

NHC graphics on Thursday morning showed that the storm is likely to head through the Carolinas and Virginia before heading out into the North Atlantic.

The storm has left at least two people dead, according to NBC News. One person was electrocuted after touching a power line in New Orleans, while police in Biloxi, Mississippi have blamed the storm for a man who was found dead in the marina on Wednesday, the outlet said.

Kathleen Flynn/Reuters

Zeta affects early voting

Zeta made landfall west of Grand Isle, Louisiana, around 5 p.m. CDT on Wednesday, with winds of 110 mph — 1 mph short of being a major Category 3 storm.

It was the fifth hurricane to strike Louisiana this year, tying a 15-year-old record, according to Reuters. Louisiana is still reeling from the lingering impacts of Hurricanes Laura and Delta earlier this season.

Zeta hit Mexico's Yucatán Peninsula as a Category 1 hurricane on Monday night, then gained strength as it crossed the Gulf of Mexico.

Louisiana, Alabama, and Mississippi all declared states of emergency in anticipation of Zeta's arrival.

New Orleans officials ordered residents to shelter in place starting Wednesday at 2 p.m. local time — likely impacting the day's voter turnout, as early voting hours typically end at 7 p.m.

Parts of the Florida panhandle also closed voting sites early because of tropical storm warnings.

Approaching a record number of named storms

The Atlantic hurricane season has hit the US Gulf Coast hard this year.

Hurricane Hanna flooded streets and caused nearly 60,000 power failures in Texas in late July.

In August, Hurricane Laura, a Category 4 storm, killed at least 33 people and caused more than $14 billion in damage as it tore through southern Louisiana, according to a report from the insurance company Aon.

And in September, Hurricane Sally killed four people and caused extensive damage in Florida and Alabama.

Hurricane Zeta is the 27th named storm in this year's Atlantic hurricane season — the second-highest number on record. The 2005 season holds the record: It had 28, including a subtropical storm that didn't get an official name.

There is still time for the 2020's record to surpass 2005's: More than a month remains in this year's hurricane season, which officially ends November 30.

Atlantic storms are named in alphabetical order, with a few letters excepted. But because this season has had more named storms than available letters, the last six have taken their names from letters in the Greek alphabet.

Kathleen Flynn/Reuters

Climate change is making hurricanes stronger and more sluggish

Climate change is making storms stronger on average, since hurricanes feed on warm water.

Warmer air also holds more atmospheric water vapor, which helps tropical storms strengthen and unleash more precipitation. On top of that, higher water temperatures lead to sea-level rise, which raises the risk of flooding.

Each new decade over the past 40 years has brought an 8% increase in the chance that a given tropical cyclone will become a major hurricane (defined as Category 3 or above).

A 2013 study found that for each degree the planet warmed over the previous 40 years, the proportion of Category 4 and 5 storms increased by 25% to 30%.

Gerald Herbert/AP Photo

"Almost all of the damage and mortality caused by hurricanes is done by major hurricanes," James Kossin, an atmospheric scientist at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, told CNN in May. "Increasing the likelihood of having a major hurricane will certainly increase this risk."

Storms are also getting more sluggish. Over the past 70 years or so, hurricanes and tropical storms have slowed about 10% on average, according to a 2018 study. That gives a hurricane more time to damage a given area.

"We have a significantly building body of evidence that these storms have already changed in very substantial ways, and all of them are dangerous," Kossin told The Washington Post.