- In the United States, Americans don’t directly elect the president.

- Instead, states appoint a number of electors equal to the number of representatives they have in Congress to the electoral college, a system that was devised in the 18th century by the founders of the United States.

- Here’s a step-by-step guide to how the electoral college process works and how the college selects a president.

- Visit Business Insider’s homepage for more stories.

In the United States, Americans don’t directly elect the president. And contrary to popular belief, there is no constitutional right to vote for president.

Instead, states appoint a number of electors equal to the number of representatives they have in Congress to the electoral college, a system that was devised in the 18th century by the founders of the United States.

All states except for Maine and Nebraska use a winner-take-all system in which the candidate who wins the most votes earns all of the state’s electoral college votes.

This system has resulted in some presidential elections - like the ones in 2000 and 2016 - in which the winner of the national popular vote loses the electoral college, sparking criticism that the electoral college is fundamentally undemocratic and disenfranchises voters.

Here's the timeline for how the electoral college will play out in 2020.

November 3, 2020: States appoint their electors

States must appoint their electors to the electoral college on the first Tuesday after the first Monday in November.

Today, all states hold popular elections to determine how their electoral college votes will be allocated, but they aren't required to do so by the constitution or by federal law. For much of America's early history, legislatures directly voted on how to appoint their electors without any input from the voters.

In most previous years, TV networks and outlets like the Associated Press have been able to call the winner on election night based on the available results.

But importantly, the results of any election are never finalized on election night. In most places, it takes officials days or weeks to fully canvass and then certify the results.

And due to the projected increase in the proportion of Americans casting mail ballots, which take longer to process and count than in-person votes, it's very likely that there won't be enough available results to declare a winner on election night.

During the canvassing process, canvassing boards, which are usually composed of county-level election officials, process and tabulate not just the votes of those who voted in person, but absentee and mail-in ballots, provisional ballots, and ballots from overseas and military voters.

The canvassing process immediately after the election is the time in which we're likely to see most of the legal challenges over which ballots should count. The Trump campaign, in particular, has signaled they are likely to challenge mail ballots for late arrival, missing postmarks, and other errors to get them disqualified.

When the canvasses are complete in each county, local election officials certify each county's result and the governor of each state certifies the statewide results. The governor then transmits a copy of the results and the names of the state's slate of electors to the National Archives.

To help visualize post-election counting, I turned @NASSorg 's resource on canvassing into a graphic. For more details, check out https://t.co/lSG3yU1tYT pic.twitter.com/foKa5DUBIL

— Charles Stewart III (@cstewartiii) August 25, 2020

December 8, 2020: Electoral colleges meet before formally voting

Six days before the electoral colleges convene to vote, electoral colleges meet on what is known as the "safe harbor" deadline by which states must certify their results without risking Congress getting involved and resolving a potential dispute over which candidate won a particular state's electoral college votes.

The safe harbor deadline came into play during the court challenges over the disputed 2000 presidential election in Florida. It could be a factor this year too if there's any serious dispute over the 2020 results.

On the day of the 2000 safe harbor deadline, the US Supreme Court ruled that Florida's varying recount policies between counties violated the Equal Protection Clause of the 14th amendment by arbitrarily valuing some votes over others.

The Court still ruled 5-4 to uphold Florida's certification of the state's electoral college votes for George W. Bush. The majority opinion was in line with the wishes of the Florida legislature, which wanted the state to certify the results and avoid leaving the winner of the state's electoral college votes to Congress.

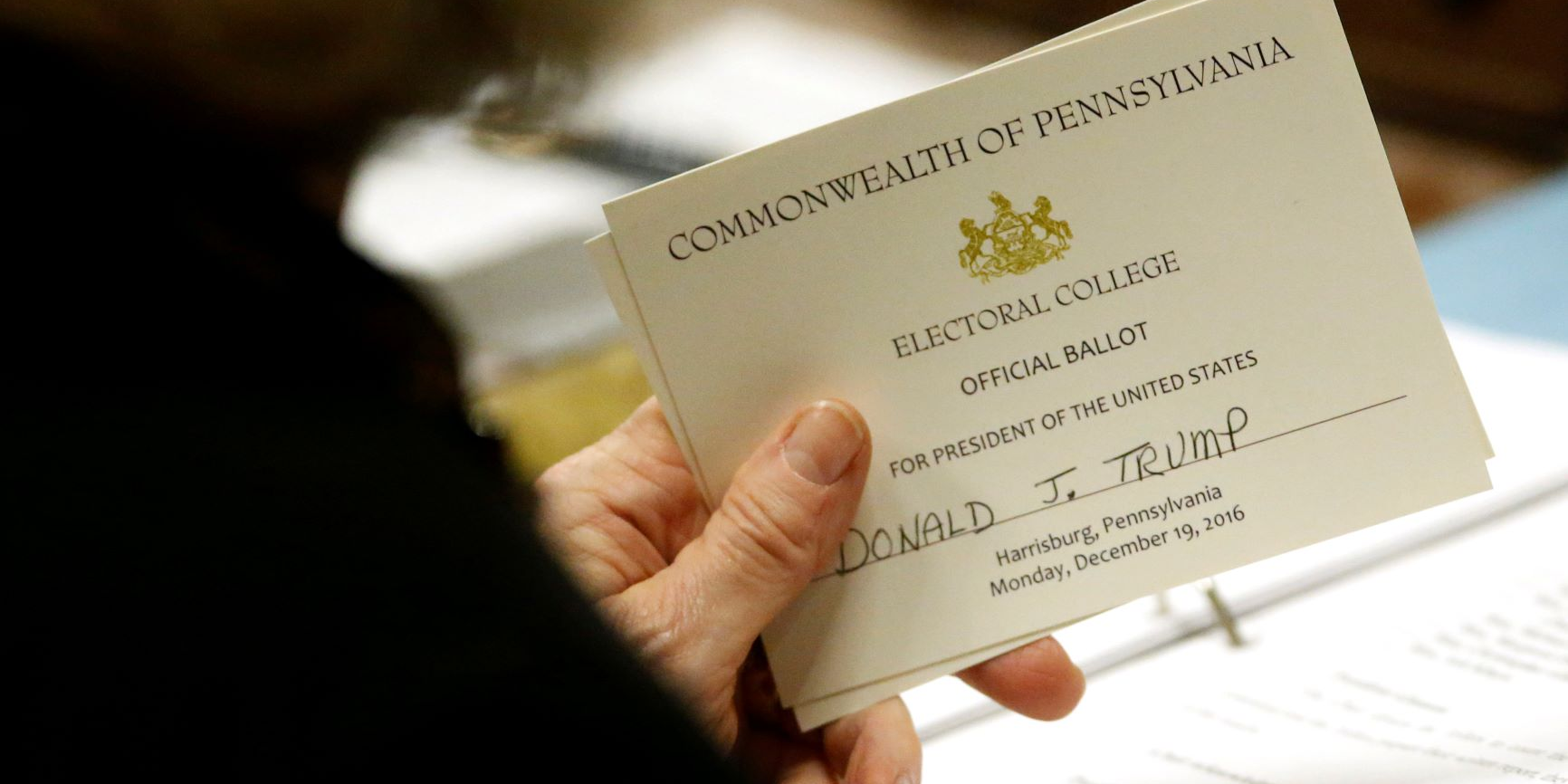

December 14, 2020: Electors vote

On the second Monday after the second Wednesday in December, electors convene in all 50 states and the District of Columbia to formally cast their votes for president and vice president. They then send certificates of their vote to their state's chief election official (in most states, this is the secretary of state), the National Archives, and the President of the US Senate.

January 6, 2021 at 1 p.m.: Vote count is finalized at the results are certified

The sitting Vice President, acting as the Senate president, presides over a joint session of Congress to read aloud the certificates cast by the electors representing all 50 states and D.C. to finalize the vote count. If no members of Congress object to any of the certificates in writing, the Senate president officially certifies the selection of the president-elect and vice president-elect.

January 20, 2021 at noon: The president is inaugurated

The president and vice president are formally inaugurated and sworn into office by the Chief Justice of the United States Supreme Court.