- Some Ukrainian surgeons are using cutting-edge medical technology to treat wounded soldiers.

- The medical device is a human acellular vessel and is designed to treat traumatic vascular injuries.

- HAVs combine the simplicity of using artificial vessels with the safety of using a person’s vein.

Last year, a new type of medical device arrived on the battlefield in the war in Ukraine.

It’s a small tube called the human acellular vessel (HAV) designed to treat traumatic vascular injuries mostly due to blasts and shrapnel.

Dr. Oleksandr Sokolov, a vascular surgeon in Ukraine, told Insider that HAVs have been used in simple vascular reconstructions as well as in contaminated and complicated wounds.

So far, HAVs have helped 18 injured military personnel and civilians.

The HAV “really makes sense in civil and military medicine, especially for treatment of blast shrapnel and gunshot injuries, during massive casualties, when every moment is very expensive,” Sokolov said.

Why vascular injuries are so dangerous

Vascular injuries are a leading cause of preventable death in military combat and a leading cause of amputation.

When a blood vessel is damaged it can lead to limb loss if the blood supply is cut off or death if damaged arteries cause too much blood loss.

Between 2009 and 2015 in Afghanistan, nearly 20% of all combat injuries suffered by US soldiers were due to vascular trauma — 70% were caused by fragments from explosions and 30% by gunshot wounds.

How HAVs reached Ukraine

Not long after Russia invaded Ukraine in 2022, surgeons in Ukraine reached out to the biotech company that created the HAV, Humacyte.

Humacyte worked with the FDA’s Office of International Programs and the Ukrainian Ministry of Health to send the still experimental HAVs to the war zone.

“We shipped vessels to five frontline hospitals around June of 2022,” said Laura Niklason, CEO and founder of Humacyte.

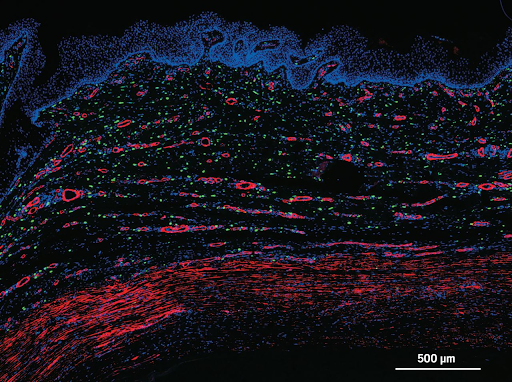

Part of what makes the HAV different and so promising is that it’s actually bioengineered from human cells.

A lab-grown replacement blood vessel

The hope is that HAVs can provide a superior option to current vascular replacement techniques.

They’re lab-grown from human vascular cells in about eight weeks and then sanitized to be ready as an off-the-shelf replacement blood vessel.

Vascular surgeons often treat traumatic vascular injuries with grafts. The preferred method involves taking a vein from one part of a patient’s body and grafting it into the injured area.

But if a vein isn’t available — for example, in a battlefield injury where all limbs sustained damage — a surgeon can use a prosthetic blood vessel made of synthetic material.

Though both of these methods can be effective, they have some drawbacks.

When using a vein from a patient’s body, harvesting the vein can lead to complications, as well as taking more time — which can be a critical factor in treating severe injuries.

Prosthetic vessels, on the other hand, are quickly available, but tend to have a high infection rate and are prone to blood clotting complications.

HAVs avoid both of these drawbacks because they’re immediately available and — since they’re made of human vascular cells — they have low infection rates, according to clinical trials.

They combine the simplicity of using artificial vessels with the safety and confidence of using a person’s own vein, Sokolov said.

Plus, over time “you can see stem cells from the patient start off on the outside of the HAV, and then over time they work their way in and become vascular cells, so this HAV becomes a new artery,” Niklason said.

HAVs don’t contain elastin, a protein that helps blood vessels contract and relax — and elastin doesn’t seem to reform as part of the HAV inside the body. But other than that, “over time it very, very much resembles a native blood vessel,” Niklosan said.

Sokolov said people in Ukraine treated with HAVs have no signs of complications since they were first used about one year ago.

“In my opinion, arterial reconstruction using an HAV is a fairly simple and reproducible technique for operating vascular surgeons,” he said.

HAVs aren’t just for battlefield blast injuries. Clinical trials are ongoing for their treatment of other traumatic injuries, such as from car accidents and workplace accidents involving heavy machinery.

Dr. Miechia Esco, a vascular surgeon experienced in treating traumatic injuries, reviewed reports of the HAV in clinical trials. She told Insider, “A bioengineered vessel universally readily available for complex vascular trauma is remarkable.”

Esco wondered what HAVs will cost if they’re mass-produced — if they are potentially more expensive than current treatment options, but said, “If the reports, Phase III trial results, and other claims of Humacyte remain consistent in what is actually observed in civilian and combat scenarios, it could be the optimal choice in select vascular trauma patients.”

What’s next?

A representative for Humactye wouldn’t share the cost of the HAV. The company is waiting until their device is FDA-approved.

But they expect HAVs will provide overall cost savings for the medical community due to fewer complications, such as infections and amputations compared to the current standard of care.

Humacyte plans to file an application with the FDA later this year for HAVs to treat traumatic vascular injuries. Niklason hopes for approval by the middle of 2024 and said scaling up production shouldn’t be an issue. The company has the capacity to grow 40,000 HAVs per year, Niklason said.