Terrell Ortiz was sitting in the passenger seat of his white Nissan Altima parked in the Bushwick neighborhood of Brooklyn, New York, when a man suspected of being a rival gang member walked up to Ortiz’s window, shot him multiple times, and fled.

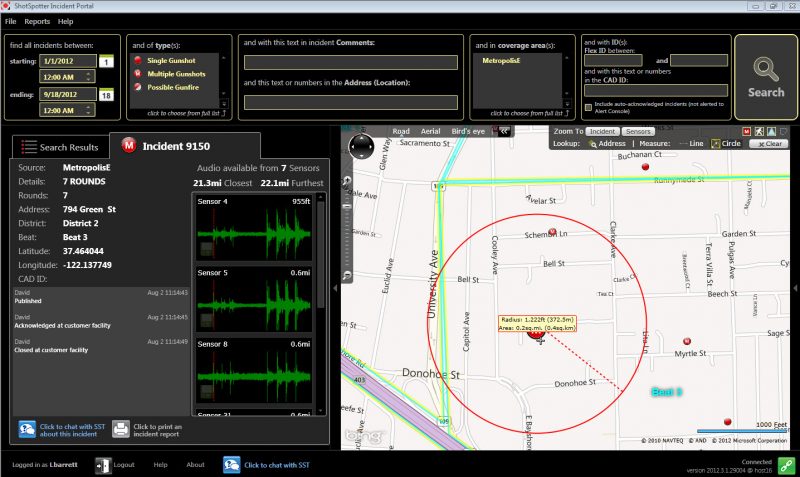

At the same moment, three rooftop microphones picked up the sounds of the shots and sent them to a computer at the New York Police Dept. and to a person in California. Together, they confirmed the noises, figured out their location, and dispatched police within minutes.

Ortiz, 26, was rushed to a nearby hospital and later pronounced dead. The shooter was never found.

11 feet away

The technology responsible for alerting the NYPD to Ortiz’s shooting is known as ShotSpotter, whose 16-year-old parent company went public on June 7. In more than 90 cities across the US, including New York, microphones placed strategically around high-crime areas pick up the sounds of gunfire and alert police to the shooting’s location via dots on a city map.

The technology builds on existing surveillance tools, many of which are aging, grainy-video cameras that don't record sound and produce footage officers review only after a crime has been committed. ShotSpotter also sends alerts to apps on cops' phones.

"We've gone to the dot and found the casings 11 feet from where the dot was, according to the GPS coordinates," Capt. David Salazar of the Milwaukee Police Dept. told Business Insider. "So it's incredibly helpful. We've saved a lot of people's lives."

When three microphones pick up a gunshot, ShotSpotter figures out where the sound comes from. Human analysts in the Newark, California, headquarters confirm the noise came from a gun (not a firecracker or some other source). The police can then locate the gunshot on a map and investigate the scene. The whole process happens "much faster" than dialing 911, Salazar said, though he wouldn't disclose the exact time.

Playing 'Moneyball' with crime

In theory, this allows departments to do a couple things. On the one hand, it lets them respond more quickly to isolated incidents. But it also lets them deploy more resources in areas with "serial shooters," or small clusters of criminals who make up the bulk of a given area's crime, according to ShotSpotter CEO Ralph Clark.

But as Ortiz's death and his assailant's getaway highlight, the company still struggles to sell its value in concrete terms. It's up to individual departments to collect and analyze their own data, and not all agencies take as much initiative as the MPD.

Some data indicate the technology still needs fine-tuning. Last year, Forbes discovered through a data analysis of more than two-dozen cities using the program, in 30% to 70% of cases, police found no evidence of a gunshot when they arrived.

Still, Clark says the program's greatest value comes in its ability to deter people from committing gun violence in the future. In a recent blog post, he compared ShotSpotter to the story of "Moneyball," in which pro baseball teams systematically overvalue certain traits in their players. In Clark's analogy, homicides are home runs (overrated) and crime deterrence is on-base percentage (underrated).

"Our view is that when police show up quickly and precisely to every single gunfire event it sends a powerful signal to those otherwise tormented residents," Clark wrote. "Each time the police show up to a gunfire incident, whether or not they make an arrest, they increase their [on-base percentage]."

Saving lives is worth millions

Clark says this approach has been effective enough for departments to renew their contracts with the company.

"They're getting value out of it," Clark told Business Insider. "It's aiding their investigations. It's enabling them to better serve communities by better showing up."

Salazar has been using ShotSpotter in Milwaukee since 2010. Previously, his department discovered just 16% of gunshot cases led to 911 calls. He knew he needed a better way to determine where shots were coming from.

"You can't do something about something you don't know about," he said. "We found out we didn't know about a lot."

Salazar says ShotSpotter has helped Milwaukee police save lives, but the real benefit is helping the department deploy officers when and where they're needed most. That, he says, is what made the millions in taxpayer dollars worth spending.

"Everybody wants to run up the hill and punch the guy in the nose who's shooting a gun off," Salazar said. "But to go there at nine in the morning, when nothing's going on, and go talk to the people in the neighborhood who have lived there for the last 15 years ... that's where you can really make a difference. That's where you can do some targeting."

'Big Brother'

Salazar says some may view the high costs as a waste of funds for what, to them, amounts to a toy with mere dots on a screen. But to get real value out of it, he said agencies must be willing to use the data, not just collect it. The technology alone can't know how many lives it saves.

Clark of ShotSpotter says that's not how it's designed anyway.

"You'll never, ever hear me say ShotSpotter is solely responsible for reductions in gun violence," Clark said. "We can't make that claim. There are a lot of things that go into a successful gun-violence-abatement strategy."

Residents of the New York neighborhood where Terrell Ortiz was shot expressed mixed feelings that a technology like ShotSpotter would be an effective crime-fighting tool. While Jose Rodriguez, a 46-year-old deli manager, shrugged off the sensors, calling them "a good thing," 60-year-old Felix Pizarro, who called himself the "mayor" of his block, said that neighbors who know one another and are friendly produce a safer environment than microphones on a roof.

"I don't like Big Brother being in all my business," Pizarro said.