- Scientists recently drilled 3,500 feet deep into the Antarctic ice to the subglacial Lake Mercer -a lake that had been untouched for thousands of years.

- They pulled up samples of water, ice, and lake mud from the depths for further study.

- When analyzing the mud, researchers found the carcasses of tiny crustaceans and a tardigrade.

- The research team has shared additional images and video from their foray into the icy depths. Take a look.

Scientists know more about the surface of Mars than they do about the environment under Antarctica’s ice sheet.

But in December, a group of scientists drilled an extremely deep hole that is revealing secrets from that frozen world.

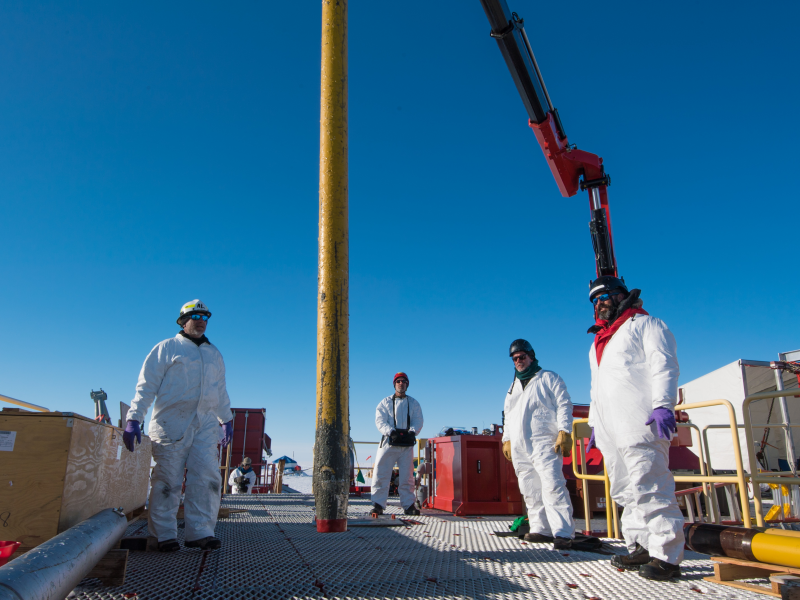

Using a hot-water drill, a roughly 40-person team from the Subglacial Antarctic Lakes Scientific Access (SALSA) project bored a hole more than a kilometer (3,556 feet) into the ice. The goal: to explore an isolated subglacial lake below, called Lake Mercer.

The team succeeded in reaching the lake, and extracted a 5.5-foot-long ice core (the longest ever from a subglacial lake), sediment cores, and water samples. The SALSA scientists expected to find microbes in those samples – similar microbial lifeforms had been dredged up from nearby subglacial Lake Whillans five years earlier.

But the samples also turned out to contain the carcasses of higher lifeforms.

The mud contained dead crustaceans no bigger than a poppy seed along with a dead tardigrade. (Also known as water bears, tardigrades are eight-legged critters that can withstand extreme temperatures and live without water for decades.)

The discovery suggests that these creatures were transported to Lake Mercer from nearby mountains (where such creatures have been found before) by moving water or an advancing glacier, Nature reported.

"We're going to change the way we look at Antarctica because of this research," John Priscu, chief scientist of the SALSA project, told Business Insider.

The SALSA team has since released images and video footage showing how they were able to bore a hole 3,556 feet deep in the ice. Take a look.

Priscu said he's been studying Antarctic lakes for 35 years.

His team's collected data about the salinity, temperature, and depth of the previously unexplored subglacial Lake Mercer.

Priscu and the SALSA team were deployed out of McMurdo Station, a US Antarctic research center, for this project.

But in order to reach the actual borehole site, the team had to travel hundreds of miles northward towards the center of the continent using specialized tractors and aircraft with skis under the wheels.

After the deep hole was drilled into the ice, the team used a gravity corer — essentially a tube that gets screwed into the ice — from the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institute to pull samples of ice and mud back to the surface.

Even though the hole in the ice was no more than 60 centimeters wide, the researchers were able to slide the corer down the nearly 1-kilometer-long chute. After it hit the sediment below, the corer, and the mud it grabbed, were pulled back to the surface.

One of the tools used by the SALSA team is called the multicorer, because it can bring up three sediment cores at a time.

In the case of Lake Mercer, the team sent down two multicorers back to back, which each retrieved three perfect sediment cores of lake mud.

To capture never-before-seen footage of the lake, the SALSA team used a torpedo-shaped robot called SCINI (Submersible Capable of Under Ice Navigation and Imaging).

Most of the images and video of Lake Mercer would not have been possible without the SCINI robot, a remote-operated vehicle (ROV) designed for this mission.

Bob Zook, chief engineer and SCINI Operator for the SALSA team, spoke affectionately of the contraption he designed and built. He calls it "Skinny."

SCINI is operated with a specially programmed PlayStation controller.

Deep SCINI Chief Engineer Bob Zook shows Outreach PI Kathy Kasic how to fly the Deep SCINI ROV during a tank test in McMurdo Station. If you look closely, you can see that they operate SCINI using a specially programmed Playstation controller! #nsfsalsa pic.twitter.com/xqaBWXdT37

— Salsa Antarctica (@SalsaAntarctica) January 24, 2019

SCINI is 7 feet long and 10 inches in diameter to allow it to fit down the hole. It has three cameras and three bright lights - "kind of important when you're traveling to a place that hasn't had light in 50,000 years," Zook said.

"It felt a little bit like we were launching a spacecraft," Zook said.

Zook said SCINI's success in capturing the first-ever footage of the subglacial lake was three years in the making.

"Our elation is palpable," he said on the SALSA project website. "It was a hell of a year."

The following images are blow-by-blows of the journey down, taken from SCINI's footage. Looking down the hole from the icy surface, the first 300 feet or so is all air.

"What you're actually looking down is a black hole of air about half a meter in diameter," Priscu said. "You don't hit water until 100 meters down."

That 300-foot gap of air is called the freeboard - the term for the distance from the surface of the ice shelf to the water level. In this case, the freeboard is about as tall as the Statue of Liberty.

"You don't want to fall in that hole," Priscu said.

The borehole was about 18 inches in diameter, Zook said.

The hole's small diameter meant that all of the tools, and all of the samples they brought up to the surface, had to fit through an opening just a bit bigger than a steering wheel.

Before anything went down the borehole, it had to be sterilized to ensure no foreign contaminants would sully the hole or the subglacial lake below.

Everything that went down, from scientific equipment to the boiling-hot water used to bore the hole, had to be sterilized.

The SALSA team used a combination of hydrogen peroxide and ultraviolet light to ensure everything was clean and sterilized. A collar at the top of the borehole bathed tools, ropes, and the SCINI robot in UV light.

"It really does nail everything," Priscu said. "It fries 'em."

The collar's UV light was so powerful, in fact, that all the SALSA team members had to wear protective goggles.

"Whenever it was on, a red light would flash on deck," Priscu said.

After a 100-meter (328-foot) journey downward, SCINI finally hit water.

Think of the journey down to Lake Mercer like a layer cake. The cake frosting is the unpacked snow that sits on top of the ice sheet. The top layer is the 100-meter-long freeboard of air, followed by almost a kilometer of water, which is separated from the 15-meter-deep subglacial lake by a layer of ice.

More than 900 meters (2,700 feet) of water separate Lake Mercer from the 100-meter-long stretch of air above.

The pressure as you go down the borehole increases, Zook said. "By the time you reach the bottom of the hole, you're looking at 1,500 pounds per square inch."

That's 100 times the atmospheric pressure at sea level.

This is the last layer the camera passed through on its journey to the subglacial lake. "We call this the star field," Priscu said. "It's about 5 meters thick of very, very clear ice with sediment particles frozen in."

Though basal ice can look like water with particles floating in it, the little pieces are actually sediment that's been stirred up from the lake below and tiny pockets of air that sit suspended in the ice.

This is the boundary between the basal ice and the subglacial lake. "On the right is the bottom of that dirty basal ice layer, and to the left is the liquid water of the lake," Priscu said.

"Lakes are reservoirs of history," he added. "The sediments of Lake Mercer are going to tell us the history of the entire subglacial system."

Finally, the camera hit rock bottom — literally.

What's interesting about the freshwater subglacial lake, Priscu said, is that the temperature was measured at minus 65 degrees Celsius (minus 85 degrees Fahrenheit), but the water is still liquid.

He said this is possible because the water in Lake Mercer is under enormous pressure. If you put water or ice under enough pressure, that lowers its freezing point.

Samples of the lake mud revealed some astonishing finds. There were not only live microbes, but also the bodies of dead crustaceans and a tardigrade. "It's the first time anything like that's been seen," Priscu said.

"The first things we did see were bacteria, a full living ecosystem," Priscu said. "Then we saw parts of crustaceans and I was like 'Whoa'."

The team won't yet release any images of the dead critters. "We need to do more work before we release things that we're not 100% about," Priscu said.

Priscu said he doesn't want to circulate images of the carcasses yet because it could compromise the team's eventual publications on their finding.

"I'm the bad guy who won't release them," Priscu laughed. "But we did a full poll and everyone's behind it."

Priscu is hoping to eventually find more carcasses to solidify the team's findings.

"If we brought only one organism back from Mars, I don't think I'd believe it," he said.

But that work will have to wait until next year.

"We're not going in the field again this year," Priscu said. "We have a ton of data already."

He added that the SALSA team's funding runs out this summer, but he plans to request additional funding to keep the team together so they can process samples and document their findings.

You can watch the full video of SCINI's journey down the the 3,556-foot borehole below.