The US House of Representatives voted on Tuesday to kill a set of Obama-era privacy regulations for internet service providers created by the Federal Communications Commission last October.

The most notable part of the rules, which has not yet taken effect, would require broadband providers such as Verizon, Comcast, and AT&T to obtain explicit consent before selling their customers’ web-browsing histories, app-usage data, and other personal information to advertisers and other third-parties.

The resolution was adopted in a 215 to 205 vote, with most Republicans in favor of the repeal and most Democrats against.

The House was voting on S.J. Res. 34, a resolution proposed earlier this month by Republican senator Jeff Flake of Arizona and co-sponsored by 24 other Republicans that broadly calls for the FCC’s rules to “have no force or effect.”

The resolution was passed by the Senate in a 50-48 party-line vote last Thursday. The resolution still needs to be signed by President Donald Trump before becoming law, though that appears to be a formality after the White House expressed its support for the repeal on Tuesday.

The resolution was proposed via the Congressional Review Act, a traditionally seldom-used law that Republicans have used more than a half-dozen times this year to repeal regulations passed by federal agencies late in the Obama administration.

Because the resolution was approved using the Congressional Review Act, the FCC will be barred from creating similar privacy regulations for internet providers, provided Trump does not have a change of heart.

What was at stake, and where Republicans and Democrats differ

The FCC's privacy rules were approved in a 3-2 party-line vote last October after months of debate.

They were created as an addendum of sorts to the 2015 Open Internet Order. That order classified the internet as a public utility and implemented the current net-neutrality rules - which legally prevent ISPs from blocking, throttling, or prioritizing websites as they see fit - but also left jurisdiction of ISPs' privacy policies up to the FCC, instead of the Federal Trade Commission, where it had been previously.

The FCC's privacy rules imposed a range of guidelines on internet providers regarding how they treat and protect consumer data. The most notable bit would've required them to obtain opt-in consent from consumers before they were able to sell "sensitive" information.

Much of what the FCC deemed "sensitive" lined up with items noted similarly in the FTC's privacy guidelines, including things like geolocation data, financial information, and health information. Notably, however, the FCC said that web-browsing and app-usage data are sensitive enough to require consumers' explicit permission before being shared with advertisers as well.

That specific provision is not scheduled to take effect until December, though. It's now extremely unlikely that it ever will take effect, but if it does, your internet provider will have to ask for permission before it's allowed to collect and sell your browsing data and other personal info to advertisers.

Even with the FCC's slightly stricter privacy guidelines, internet providers would still be able to collect and sell some types of personal data, such as email addresses, without seeking permission first. Consumers would be able to manually opt-out of such policies.

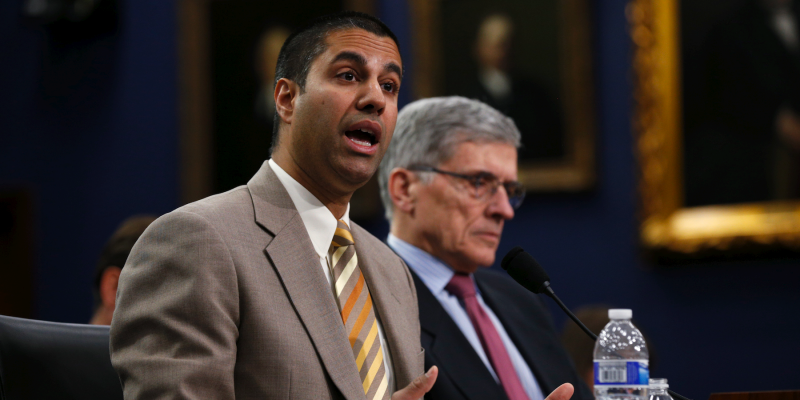

FCC chairman Ajit Pai and other Republicans oppose the agency's privacy rules because they feel the regulations unfairly target internet service providers more than internet companies such as Google and Facebook.

Those kind of companies' privacy policies are regulated under the looser FTC guidelines, which do not recommend opt-in consent for web-browsing and app-usage history. This is part of why you may see ads personalized to your browsing history as you surf the web.

Internet service providers feel this discrepancy gives those companies an unjust leg up in the digital advertising space. Groups representing ISPs previously petitioned the FCC to repeal the privacy rules altogether, and return jurisdiction of their privacy policies to the FTC.

The rollback comes at a time when internet service providers such as Verizon and Comcast are increasingly looking to boost their digital advertising presence. Google and Facebook currently dominate the digital advertising market.

Though the FCC's privacy rules do not apply to them, groups representing those internet companies previously requested Congress to repeal the regulations, mainly because they do not want the rules to set a precedent for how their data collection policies may be governed in the future.

GOP officials say that the FCC overstepped its bounds as a federal agency by creating the privacy rules, and that the regulations are too burdensome for internet providers. Deregulatory-minded Republicans have frequently used this line of attack toward Obama-era FCC policies since the 2015 net-neutrality order.

Democrats and consumer advocacy groups argue that the imbalance in privacy regulation is justified because internet providers are more easily capable of seeing everything a consumer does over their internet connection. (Though it's worth noting that companies like Google and Facebook are capable of tracking customers beyond their own websites to an extent.)

Democrats also argue that it is generally more difficult to switch internet providers than switch websites, particularly in rural or lower-income areas where competition between ISPs is scarce. They also note that websites like Google and Facebook provide largely free services in exchange for their data collection and targeted ads, whereas ISPs charge fees for their core services.

It all comes back to Title II

Pai and other GOP members want to return both broadband providers and internet companies to the FTC's less-stringent privacy rules. Pai, like many Republicans, is a noted critic of how the 2015 net-neutrality order reclassified broadband providers as "common carriers" - that is, companies that deliver a public utility, which the internet is now considered after the 2015 order - and says it has depressed investment in broadband networks. (Though the jury may still be out on that.)

In general, Pai has opposed most of the major FCC policies passed during the Obama administration, many of which have put ISPs under a more critical legal microscope. He has called for a "light-touch" approach to regulation in response. In February, for instance, he stopped an inquiry into the "zero-rating" practices of certain broadband providers, which critics say violate the spirit of the net-neutrality laws.

However, until he or GOP members of Congress are able to undo the net-neutrality order, Pai has expressed a desire to create a privacy framework that is consistent with the FTC's less-stringent guidelines.

Pai echoed this sentiment in a statement applauding the House vote on Tuesday.

"Last year, the Federal Communications Commission pushed through, on a party-line vote, privacy regulations designed to benefit one group of favored companies over another group of disfavored companies," he said. "Appropriately, Congress has passed a resolution to reject this approach of picking winners and losers before it takes effect."

But if Trump signs the resolution, there are currently doubts as to whether or not broadband providers will be legally subject to privacy-related regulation from either the FCC or the FTC.

In the former's case, Pai has said the FCC will still be able to enforce ISPs' privacy policies on a case-by-case basis using Title II, Section 222 of the Communications Act. That grants the FCC authority over ISPs' treatment of consumer data on a broader level, but it was written in 1996 with telephone services in mind, and makes no specific mention of things like web-browsing or app-usage data.

Title II is also the classification that gave the FCC much of its legal authority over ISPs through the 2015 net-neutrality order. It is what Pai and the GOP most strongly oppose about that order. If that jurisdiction is weakened, it could nullify the FCC's ability to use Sec. 222 for privacy regulation of ISPs in the first place.

If the net-neutrality order does stay in place - thus leaving the FCC in charge of ISPs' privacy regulations - it'd be unclear how far the FCC could go in writing new privacy rules in the future if Trump signs the resolution. Because the resolution uses the Congressional Review Act, the FCC would be prevented from writing any privacy rules that are "substantially similar" to the ones that are now close to being abolished. That could take any FCC requirement regarding opt-in consent for web-browsing and app-usage data off the books for good.

Meanwhile, the FTC's ability to regulate broadband providers is currently in doubt thanks to an appeals-court ruling last year that said AT&T was exempt from FTC jurisdiction altogether due to its status as a "common carrier." That, again, is a title that was applied to all broadband providers through the 2015 net-neutrality order.

The GOP could rectify that in part by undoing the net-neutrality rules, but since some ISPs like AT&T and Verizon offer mobile telephone services in addition to broadband, they would still be considered "common carriers," and thus could still be exempt from FTC oversight per the appeals court ruling.

This could make legally requiring certain ISPs to obtain either opt-in or opt-out consent for any sensitive information tricky. (ISPs such Charter and Comcast that do not provide phone services would be more affected.) Further Congressional action would then be needed to return FTC oversight to all ISPs' privacy practices, should it come to that.

Along those lines, Republican representative Bob Latta of Ohio said on Tuesday that he plans to introduce legislation that'd return some jurisdiction of common carriers to the FTC. But it remains to be seen how far that'd go, or, as is likely, if it'd still require the GOP to undo the 2015 net-neutrality order - and thus remove the common carrier label from all internet providers - to let the FTC legally enforce ISPs' privacy policies completely.

Numerous House Democrats excoriated the resolution on Tuesday as taking too much control over personal data out of consumers' hands.

"This resolution is of the swamp, and for the swamp, and no-one else," said Democratic representative Michael Doyle of Pennsylvania, referring to prior requests from broadband and internet company groups to repeal the privacy rules.

In any case, it does not look like broadband providers will need your permission before selling your web-browsing and app-usage histories any time soon. Though it doesn't change much about how you interact with the internet today, the privacy rules' apparent demise is a long-term victory for ISPs, advertisers, and internet companies, a lost opportunity for privacy hawks, and the latest step in an overarching GOP rollback of the internet regulations set by the FCC during the Obama administration.