- More than 50 years ago, Aberfan, a small coal mining town in Wales, was irreversibly changed in a few minutes when 144 people, mostly school children, were killed by a coal-waste landslide.

- What made it worse was that it was a mistake. An investigative tribunal found Wales’ National Coal Board was entirely at fault for the slip.

- The disaster has come back into focus, because it’s one of the key storylines in season three of “The Crown.”

- Visit Business Insider’s homepage for more stories.

It was one of the United Kingdom’s worst tragedies, and it was a man-made disaster.

In 1966, 300,000 cubic yards of coal sludge buried a Welsh primary school, and 19 houses in Aberfan, Wales. Hundreds of people tried to dig the school children, teachers, and people who lived nearby, from out of the wreckage, but 144 people died.

In an in-depth article titled “Aberfan: The mistake that cost a village its children,” the BBC’s Ceri Jackson, called the disaster and its lingering effects, an “obscenity,” and “an upsetting reminder of perhaps why and how much our society changed so much in little over a generation.”

A year after the disaster, an investigative tribunal ruled that the National Coal Board was entirely to blame, although it wasn’t villainy, but ineptitude.

The disaster has come back into the focus, because it's one of the key storylines in season three of "The Crown." Queen Elizabeth held off visiting for eight days, and when she did, she cried in public, which was highly unusual. Taking as long as she did is meant to be one of her biggest regrets.

Here's how the tragedy happened, in photos.

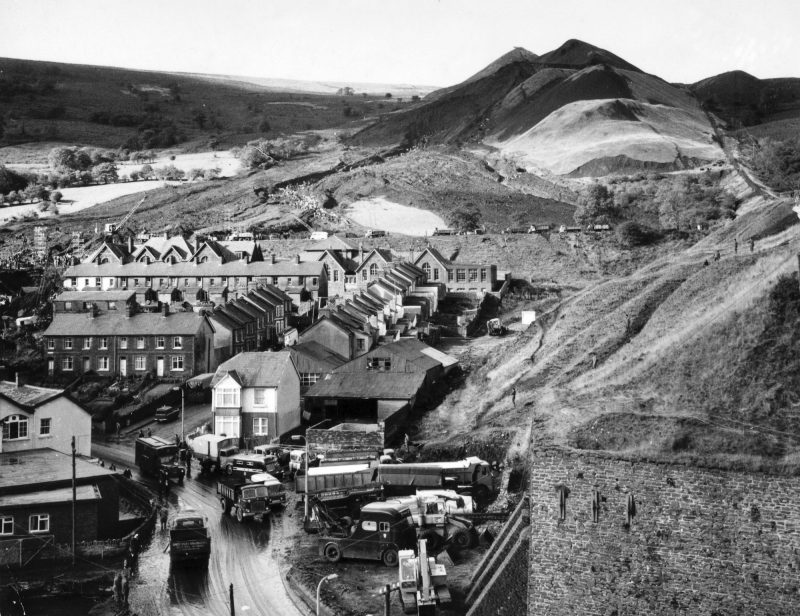

On October 21, 1966, it had been raining heavily for a week in Aberfan, a small mining town in south Wales, which sat in the shadow of the Merthyr Vale coal mine.

Source: Wales Online, BBC

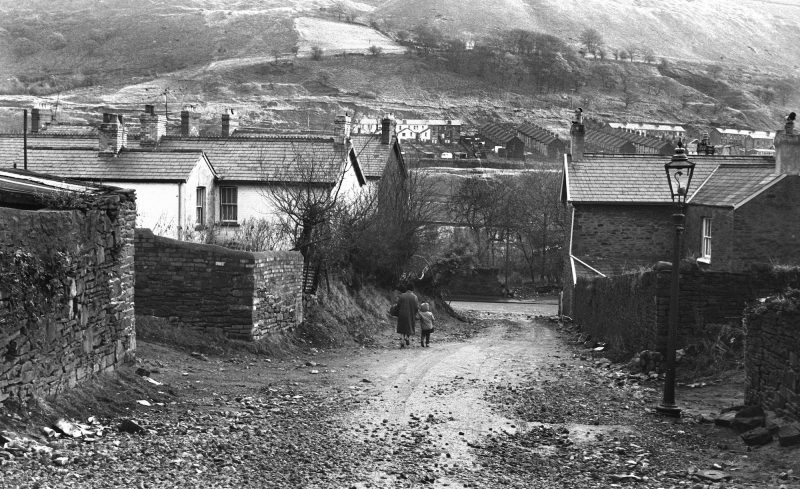

It was a drizzly morning, with low clouds. Students walked to school, for the last half-day of term. Yvonne Price, a 21-year-old police officer at the time, told Wales Online the weather was "nasty," while Reverend Irving Penberthy, who was driving that morning, said it was so misty he could barely see across the valley.

Source: Wales Online

At the edge of the Merthyr Vale coal mine were seven massive sludge piles, or spoil tips, made of coal waste. Complaints had been made to the National Coal Board (NCB) multiple times. Three years earlier, in 1963, Pantglas school wrote a petition asking for it to be looked into. The tip that particularly raised concerns was 111 feet high, and a quarter of a mile above the school. All that separated them was a steep slope.

Source: BBC

But there was an uneven power dynamic, because mining was an important part of the town's economy. Coal mines provided a steady income for about 800 miners in the area. So complaints about the spoil tips, which were not solid, and sat precariously on sandstone and a natural spring, could be ignored. There was an implicit threat that if the complaints continued the mines would close.

Sources: BBC, Smithsonian

Despite being ignored, the complaints were well-founded. Aberfan had already had two coal-waste slides — in 1944 and 1963. But the NCB was well-liked, and was seen as one of the main reasons why the coal industry was still alive. Some who had concerns didn't speak out because unemployment was a bigger concern.

At 9 a.m. school began. Ros Bastow, who was seven at the time, told Wales Online she could remember she and her peers were damp, sitting inside. Jeff Edwards, who was eight at the time, remembered the lights in the classrooms, hanging on long wires, beginning to shake.

Source: Wales Online

Everyone heard the sound. It was a deep rumble. One teacher told his class not to worry, that it was only thunder, while Brian Williams, who was seven at the time, told Wales Online the sound of the sludge was like an airplane about to land.

Source: Wales Online

At 9.15 a.m., 300,000 cubic yards of coal sludge came sliding down the hill at more than 80 mph, and engulfed Pantglas Junior School, and 19 houses. Alun Davies, who was 16 at the time, told Wales Online, it was like a black cloak had enveloped the mountain.

Sources: Wales Online, Smithsonian

The damage was instant and terrifying. Four classrooms were breached by the waste.

Sources: BBC, Smithsonian

People stood in the streets dazed, unable to comprehend what had happened. Cyril Vaughan, a teacher at the neighboring school, told BBC seconds after it hit it was quiet. "As if nature had realized that a tremendous mistake had been made and nature was speechless."

Source: Wales Online, BBC, Smithsonian

News reports said the scene looked like a bomb had gone off, or an earthquake had ripped through the town.

Source: BBC

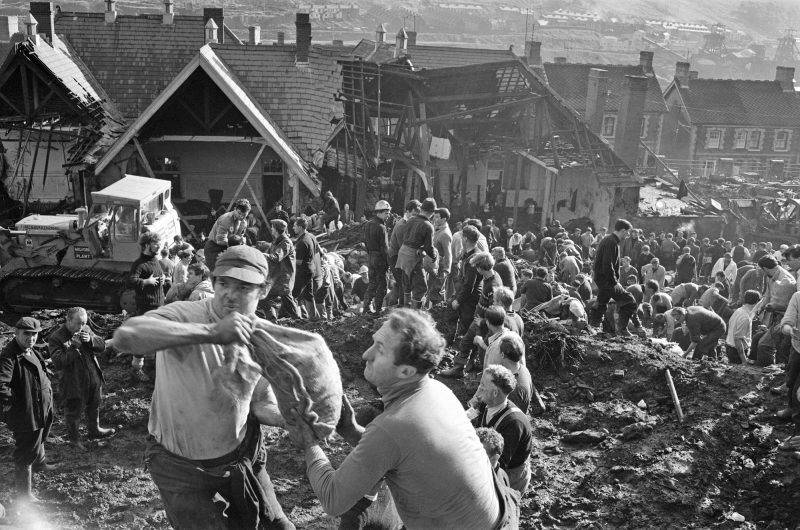

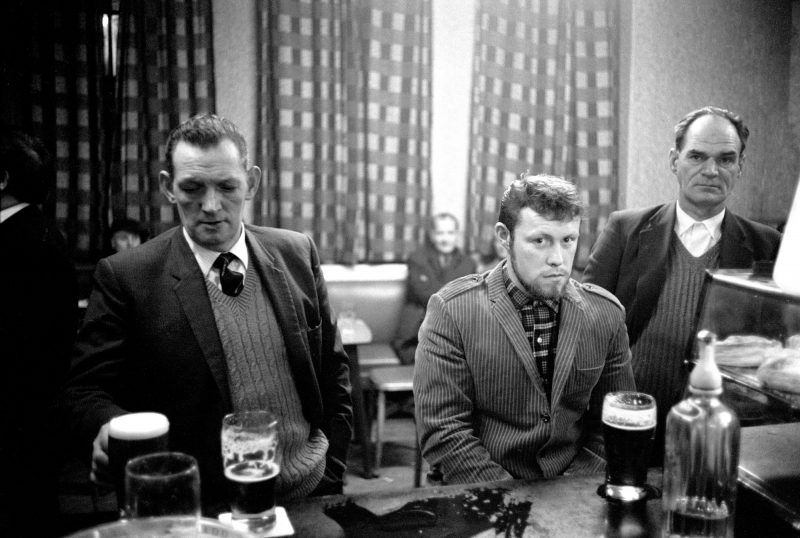

Hundreds of people began to dig. Miners still had their headlamps on.

Source: BBC

Locals and arriving emergency services worked as quickly as they could, digging through the coal-waste for survivors. They formed lines to move buckets of the sludge. In the photo below, two men are using sand bags full of mud to make a wall in case of further landslides.

Source: Wales Online, BBC, Smithsonian

Every time someone was found in the rubble, a whistle would go out, and workers went silent as they listened for any sign of life. When someone was found, they were passed through windows on stretchers.

Sources: Wales Online, BBC

Here, a policeman named Victor Jones carries a little girl named Susan Maybank from the wreckage while a woman looks to see if she recognizes her.

The last person found alive was a boy named Jeff Edwards at 11 a.m. but no one knew that, and no one stopped. The work would continue without rest, except for a quick bewildered cigarette.

Source: Smithsonian

Work went on late into the night. Life Magazine's London bureau chief told the BBC: "No one who endured this night would ever forget it – the phantasmagoria of coal dust and smoke."

Source: BBC

Despite the hard work of miners, emergency workers, and civilians, 116 children, mostly aged between seven and 11, died. The majority died from asphyxiation, and others died from the impact. The police designated the local chapel for the mortuary.

Sources: BBC, Wales Online

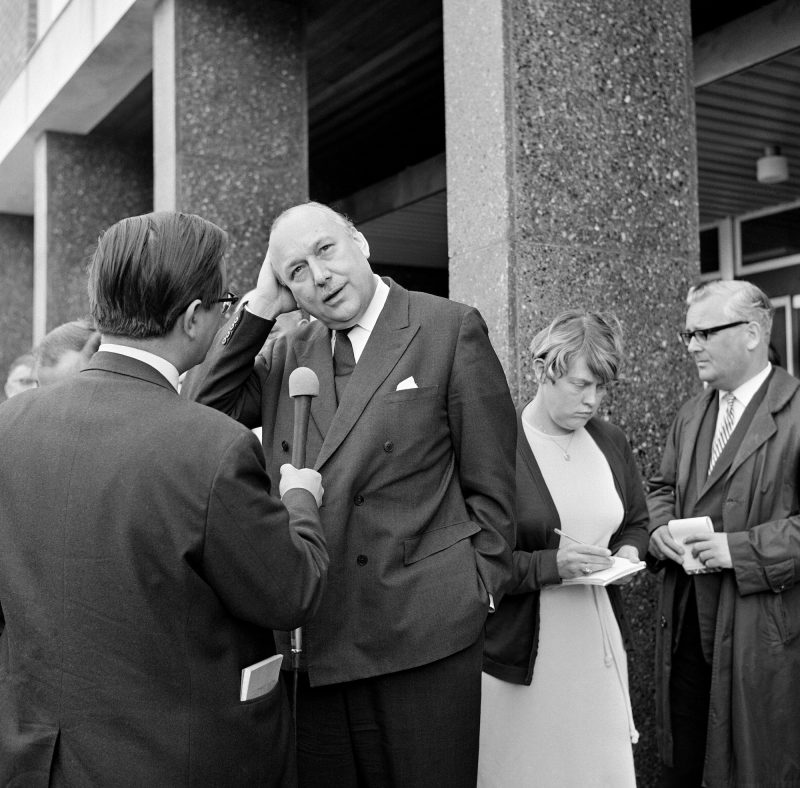

Cliff Michelmore was one of the television reporters at the scene. In his first report, he said: "Never in my life have I seen anything like this. I hope I shall never see anything like it again. For years of course the miners have been used to … disaster. Today for the first time in history the roll call was called in the street. It was the miners' children."

Source: BBC

It was a horrifying process to identify the children. The blanketed bodies were taken into Bethania chapel, and it was mostly fathers came to check who they were, lifting the blanket and returning it, until they found their child. Because the chapel was so cramped, only two families could take a look at one time. It took up to six days for some families to find the bodies of their children.

Sources: Wales Online, BBC

It wasn't a total loss. Thanks to the relentless hard work, 28 children were dug out of the rubble and survived.

Source: Esquire

Eight days after the disaster, Queen Elizabeth II visited. She cried in public, which was rare. She later said she regretted not going right away, but she'd chosen not to on purpose, so that the attention would continue to be on recovery, and not on her. Instead, she sent her husband Prince Phillip before her.

Sources: Smithsonian, Town and Country Magazine

She's visited another three times over the years. Here she lays a wreath in 1973 to commemorate the disaster.

Source: Town and Country Magazine

Along with her visit, the disaster got a lot of attention — it was the first time such a disaster had been televised. 90,000 donations came pouring in from around the world, worth more than $25 million at current exchange rates. The only time it was eclipsed was by Princess Diana's memorial fund. Despite the generosity, this fund became known as Aberfan's "second disaster."

Funerals took place for those who had died. But families had to fight for money from the fund for their children's gravestones.

In regards to compensation, Wales' charity commission considered asking parents "exactly how close were you to your child?" It was looking to refuse compensation for those who weren't deemed close enough to their children. But the question was never asked. The commission ended up providing about $645 to each family, because it was advised anymore would ruin the lives of the working class people, who wouldn't be used to large sums of money.

There was also a struggle to get rid of the rest of the coal-waste tips. Locals argued it was a psychological burden to have the remaining tips looming over their town. But it took protesters dumping coal waste in the Welsh Office for the government to agree to get rid of them. But the NCB wouldn't do it, so the government had to, and it took about $165,000 from the disaster fund for the clean up.

In 1967, an investigative tribunal, looking at who was at fault, ran for 76 days — then the longest ever in Britain. The NCB said the disaster had been an act of god, while families said the opposite, and called for death certificates to say the cause was "buried alive by the coal board." The tribunal found it wasn't "villainy," but "bungling ineptitude." It found the NCB was entirely at fault.

Sources: BBC, Smithsonian

One of the key figures was NCB chairman Lord Robens, who had argued it was impossible to predict, but then later admitted to being at fault. He made things worse for the families by making the tribunal go for several weeks longer than was necessary. He had already been criticized for not going straight to the disaster, and instead attending a ceremony establishing him as University of Surrey's chancellor.

Sources: BBC, Telegraph, Esquire

In the end, no one faced criminal sentencing, nor was anyone fired, or fined. Robens continued to have a political career, and ending up reviewing public health and safety for the British government.

Sources: BBC, Telegraph, Esquire

And while the NCB faced no lasting repercussions, Aberfan couldn't move on. Dr Arthur Jones, a local doctor, told BBC the grieving town was consumed by things like guilt and alcoholism. He called it "a village of excessive sickness."

Source: BBC

Jones said the disaster caused a rift in the town. There was a "strange bitterness between families who lost children and those who hadn't; people just could not help it," he said. It was also a time before people spoke about their feelings, and kept their thoughts to themselves. Many experienced post-traumatic stress disorder.

Source: BBC

For those who had survived, it was a long-lasting psychological burden. Jones told the BBC that children had their childhoods taken from them. "Play is an important part of a child's development but that stopped. Most of the kids we played with were gone and play was frowned upon by some parents who lost children."

Source: BBC

On the 50th anniversary, Wales remembered the tragedy with a minute of silence. Queen Elizabeth II also had Prince Charles read out a speech that said she was "deeply impressed by the remarkable fortitude, dignity and indomitable spirit that characterizes the people of this village and the surrounding valleys."

Source: Town and Country Magazine

Now, to remember the tragedy, people can walk through Aberfan's well-tended cemetery and gardens of remembrance, which is shaped in classroom-sized rectangles. And, as journalist Huw Edwards wrote, no one can leave unmoved.

Source: Telegraph