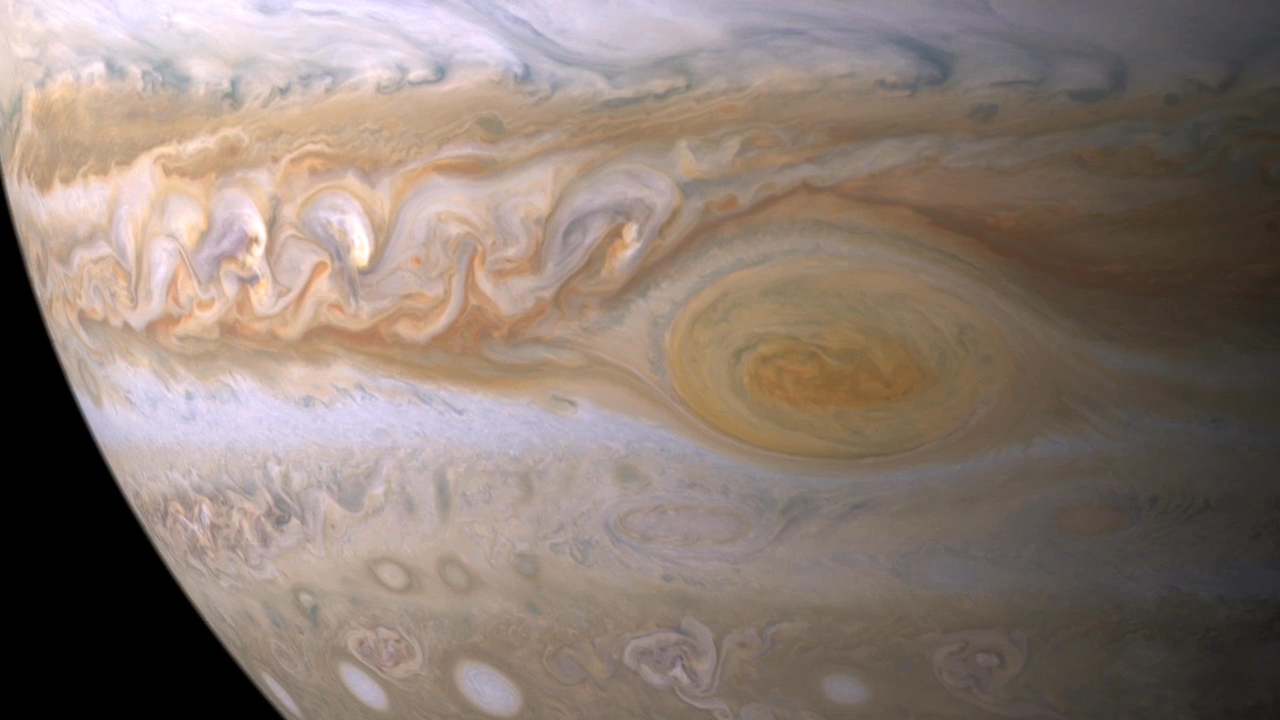

The Great Red Spot of Jupiter is about twice the size of Earth, blows winds at speeds of about 400 mph, and has blemished the planet’s atmosphere for more than 350 years.

But the spot’s grandeur is matched only by its mystery: Jupiter is very far away – about 489 million miles – so few probes have ever visited the planet, let alone flown near its crimson-colored super-storm. In fact, the best views of the Great Red Spot most often come from NASA’s Hubble Space Telescope, which orbits Earth.

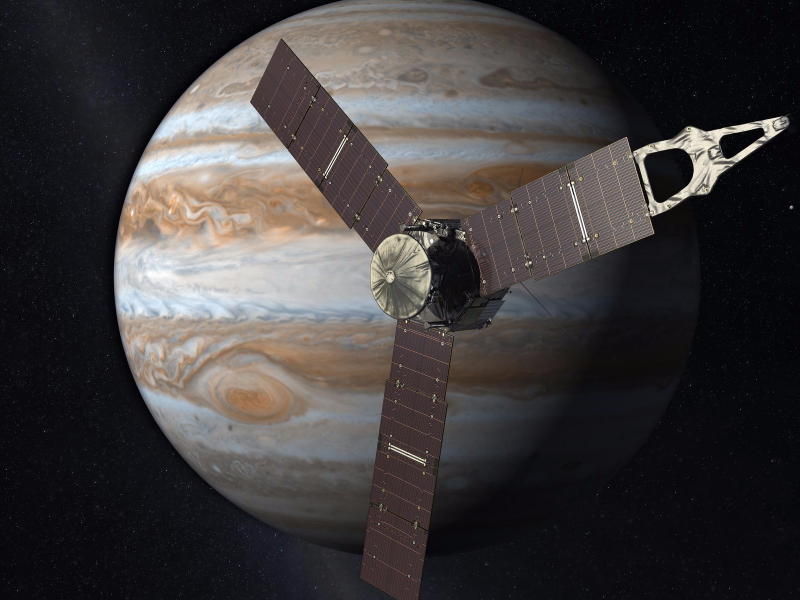

However, NASA’s Juno spacecraft is expected to fly over the Great Red Spot on July 10 and beam back the closest-ever views of biggest, baddest storm in the solar system.

“This monumental storm has raged on the solar system’s biggest planet for centuries,” Scott Bolton, a planetary scientist at the Southwest Research Institute in San Antonio and the Juno mission’s leader, said in a NASA statement. “Now, Juno and her cloud-penetrating science instruments will dive in to see how deep the roots of this storm go, and help us understand how this giant storm works and what makes it so special.”

Juno, a $1 billion robot the size of a basketball court, settled into orbit around Jupiter on July 4, 2016.

The decked-out probe has photographed Jupiter's poles for the first time, discovered atmospheric "rivers" of ammonia, watched 870-mile-wide cyclones swirl, recorded mysterious auroras, and probed deep into the planet's thick cloud tops for evidence of a solid core.

Juno hasn't yet taken close-up images of the Great Red Spot, however, because Jupiter rotates quickly (nearly once every 10 Earth hours) and the probe's visits are fast and infrequent.

Juno's orbit around Jupiter is elliptical, so it only swings by the planet once every 53.5 days. (NASA wanted to increase the frequency of these flybys to every two weeks, but that operation was scrubbed due to some sticky engine valves.) When it does get close, Juno accelerates to speeds of 130,000 mph over the planet's surface. That minimizes the robot's time inside Jupiter's belts of electronics-damaging radiation, yet reduces observing time.

Juno completed its sixth orbit, or "perijove," on May 19 and recorded a fresh batch of images. The next fly-by happens on July 10, after which time we'll finally see the Great Red Spot up-close.

Photos from previous orbits give a sense of the kind of pictures that Juno could return. Below is a shot of Jupiter's "Little Red Spot," which is about as wide as Earth:

But NASA won't fly Juno forever.

The space agency expects to kill its probe in 2018 or 2019 by plunging it into the seemingly bottomless, noxious clouds of Jupiter. The goal is to keep Juno from disrupting any aliens - microbial or otherwise - that might live in hidden oceans of water below the icy shells of Jupiter's moons Europa and Ganymede.