On May 5, 2000, the computer worm ILOVEYOU began spreading around the world.

Originating in the Philippines, the virus tricked its victims into opening an email attachment with the filename “LOVE-LETTER-FOR-YOU.txt.vbs.” Once infected, the victim spammed their email contacts -a chain reaction that led to tens of millions of infected computers around the world. It caused a staggering $15 billion (£12 billion) in damage.

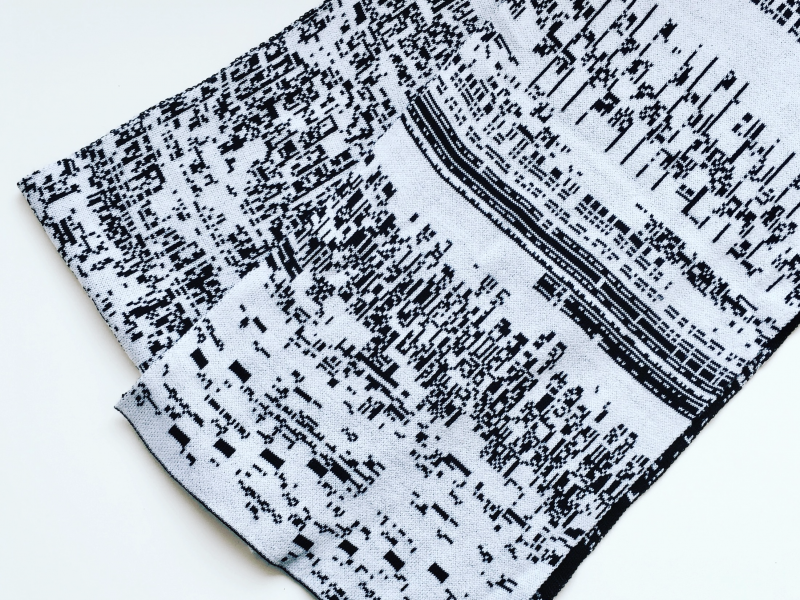

Today, you can buy ILOVEYOU as a scarf.

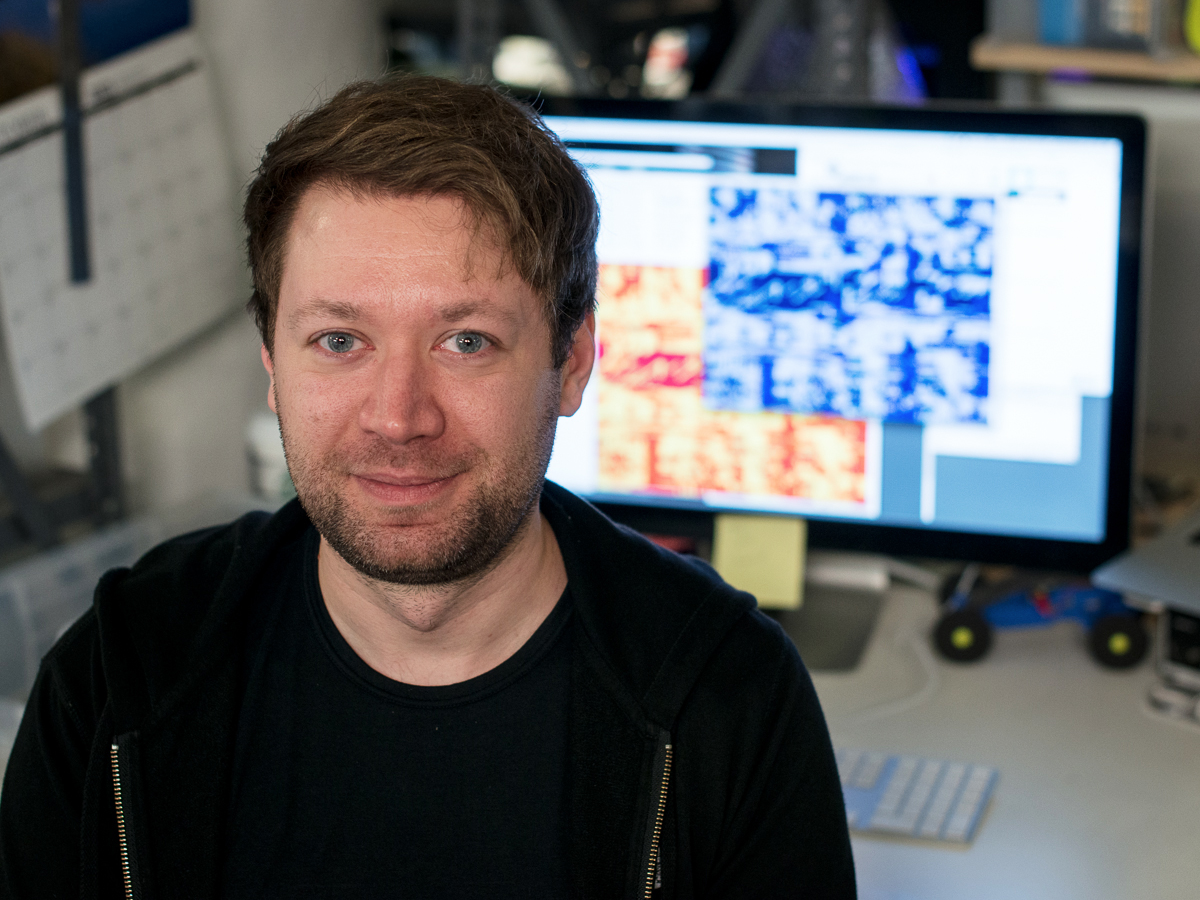

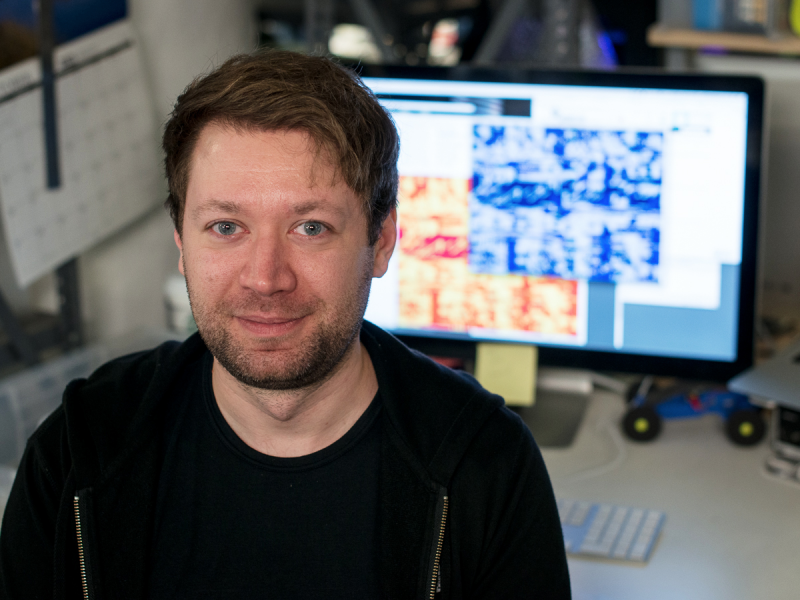

Jeff Donaldson – better known by his pseudonym “Glitchaus” – is a textile designer and artist who creates “glitch art.” It’s a genre of futuristic artwork that draws inspiration from glitches and malfunctions in computer software – working primarily in textiles.

This interest in the aberrant side of computing led Donaldson to begin studying the code of computer viruses, which sparked a realisation. “What I noticed was these viruses are so tiny … so they can be viral … they fit perfectly within a knit scarf. Which I thought was just too good not to do.”

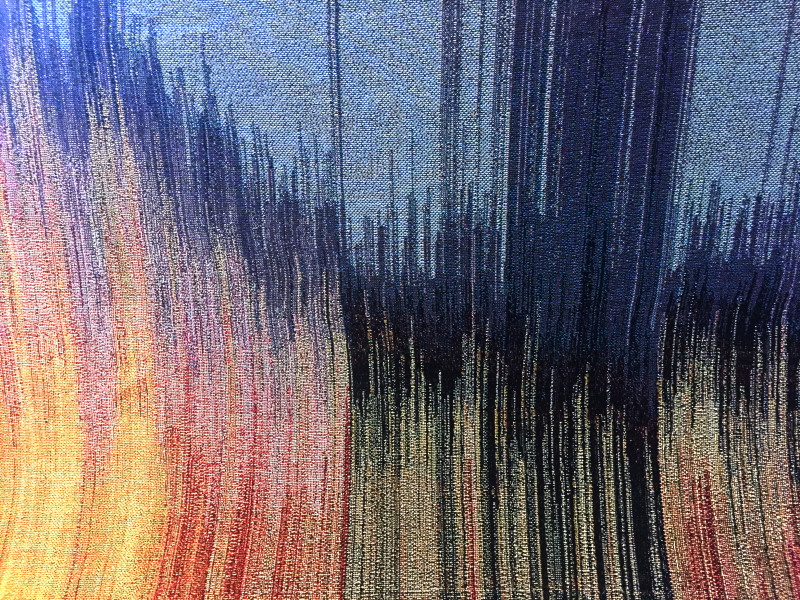

That epiphany led to his current series "Malwear." With the help of specialised software, the 40-year-old artist converts the code that underpins some of the most notorious pieces of malware of all time into fabric stitches, which can then be kitted into scarfs and throws.

If you wanted to, you could even reverse-engineer them - recreating the original virus' source code from nothing but the knitwear.

There are three in the series so far. First, there's ILOVEYOU.

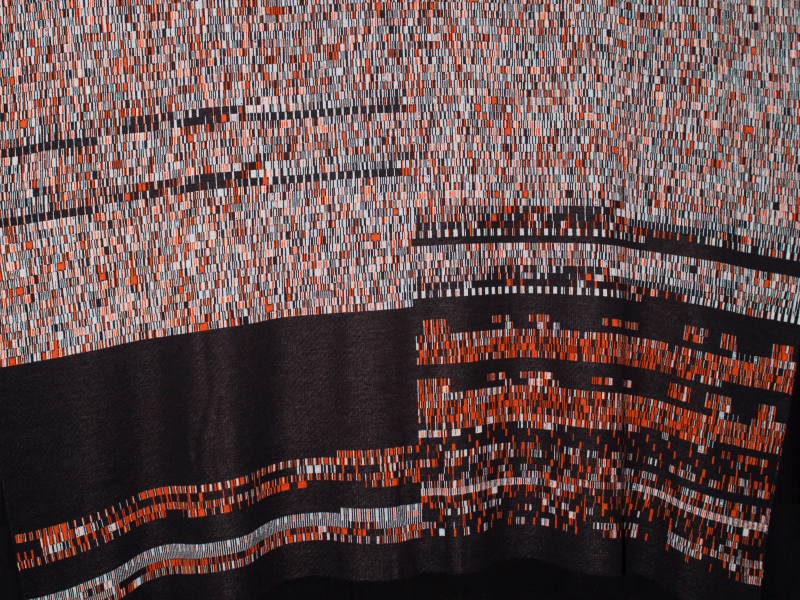

There's also Melissa, a notorious virus from 1999 that spread via email.

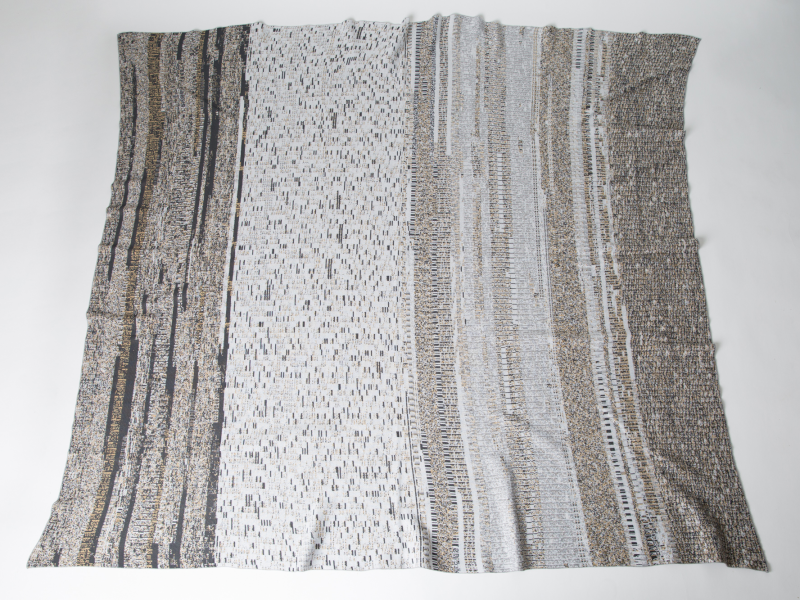

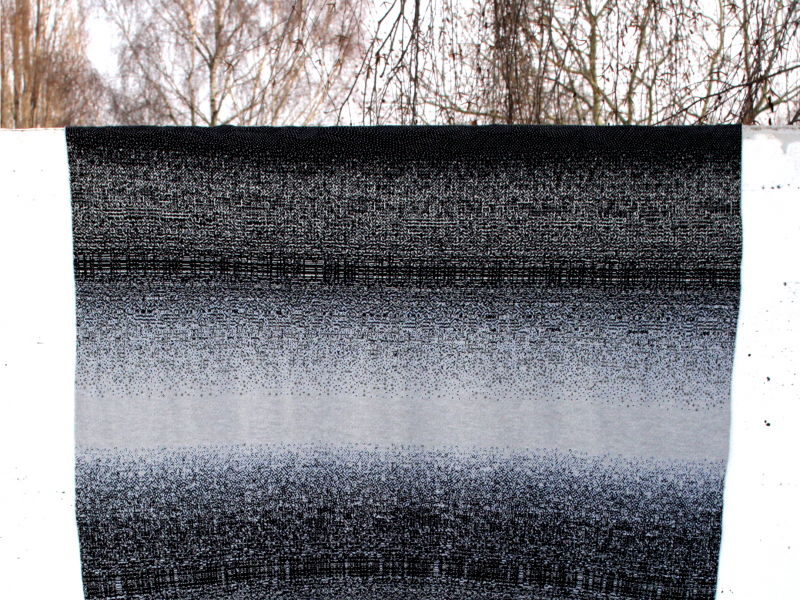

And lastly, there is Stuxnet — a devastating cyber-weapon developed by US and Israeli spies to covertly destroy Iran's nuclear centrifuges. Because of its awesome complexity, it wouldn't fit on a scarf. Instead, its code makes up an entire throw.

Some of Donaldson's earliest glitch art work modded and manipulated old video games consoles to create looping patterns. Ironically, given the imagery's source, "the results reminded me of traditional textile motifs."

Donaldson takes a different approach to glitch art to many other practitioners, he says — in part due to his background studying music. Many artists are drawn in by the technical aspects of it, but "I see it as an extension of Eastern philosophy ... appreciating the imperfections in things."

So why textiles? Why scarfs? He is "interested in extending the traditions of textile designs" into the modern age.

Textiles, historically, were "instruments of communication," Donaldson explains. Ghanese Kente cloth colours have symbolic meanings; Fair Isle knits have symbols reflecting their origins.

Donaldson "hope[s] to extend this vocabulary into the digital now, by taking binaries of one of the most encoded human constructions and using that as a source of motif creation as well as embedded information."

Some of his work is displayed in galleries, but if you're looking to buy a Malwear piece for yourself — it doesn't come cheap. An ILOVEYOU scarf is $110 (£89); the Stuxnet Data Knit blanket is $365 (£296).

So what's next for Glitchaus?

Donaldson is interested in "expanding beyond throws and scarfs into more things like wearable apparel."

And he's considering Klez, MyDoom, and Mirai — the open source software powering an internet-of-things botnet that took down much of America's internet in October — as candidates for the next Malwear project.

The designer is also speaking to institutions about branching out into woven fabrics — allowing him to create far more complex, data-rich projects. If "knits are an 8-bit resolution," he explains, "woven are a HD resolution." Donaldson might have started out playing with retro, pixellated games consoles, but now he wants to go 4K.