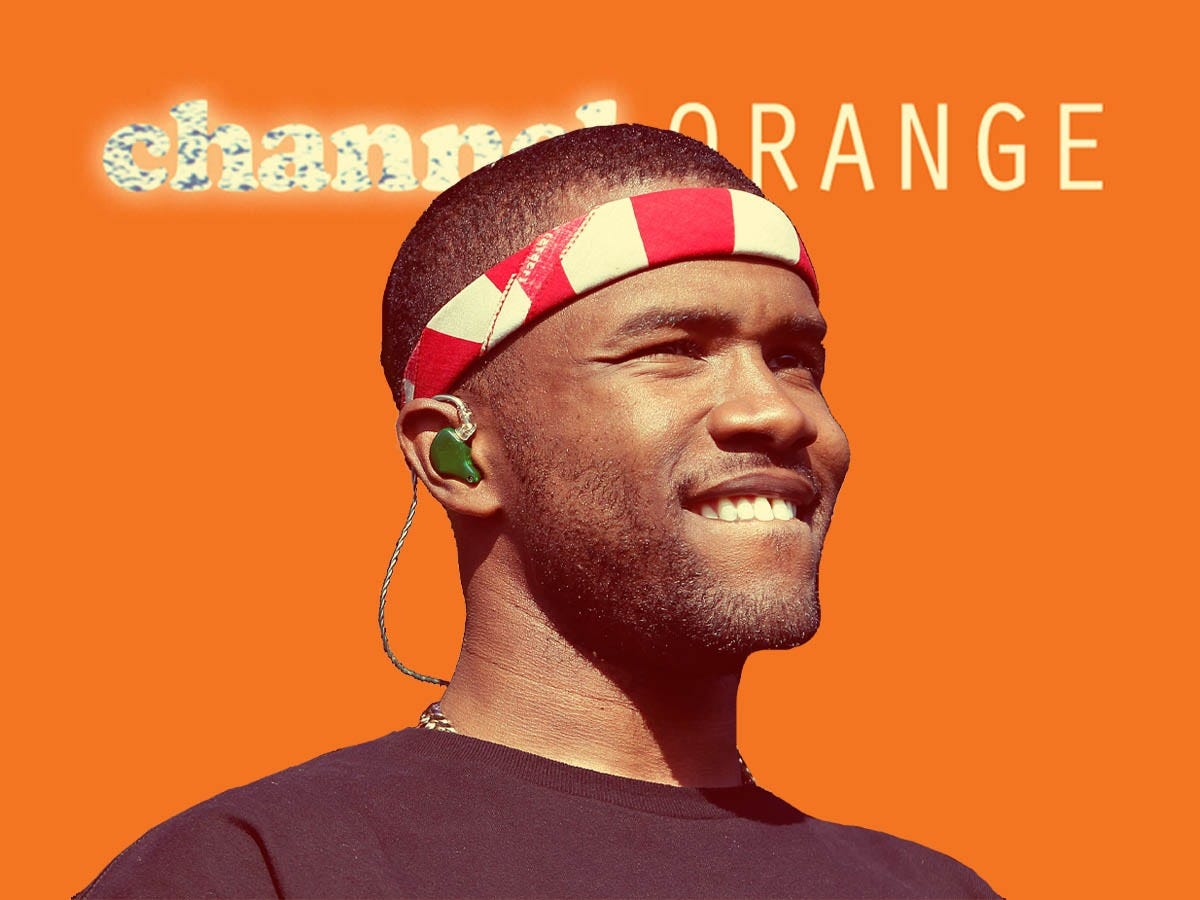

- Frank Ocean’s debut studio album “Channel Orange” was released on July 10, 2012.

- The album was immediately met with acclaim and became an instant classic. It debuted at No. 2 on the Billboard 200 and won the Grammy Award for best urban contemporary album.

- Moreover, it has influenced an entire generation of post-genre artists and changed the landscape of popular music.

- Eight years later, we still haven’t heard anything like “Channel Orange” – but there are shades of Ocean’s seminal work in everything from Lil Nas X’s “Old Town Road” to Billie Eilish’s “When We All Fall Asleep, Where Do We Go?”

- Perhaps most notably, “Channel Orange” created a more open and accepting environment for queer artists, especially in historically Black spaces.

- Visit Insider’s homepage for more stories.

On July 10, 2012, Frank Ocean released his debut studio album.

“Channel Orange” was preceded by a critically acclaimed mixtape (2011’s “Nostalgia, Ultra”) and a fairly buzzy lead single. But on a mainstream level, no one knew quite what to expect from Ocean, who finally had the funds and support from his label to execute a fully fledged vision.

As it turned out, any expectation or prediction probably would’ve been wrong anyway.

“Channel Orange” landed with the crash and curiousness of a meteor, arriving when the forecast only predicted rain. It made Ocean an icon, almost overnight – and we continue to feel its impact today.

'Channel Orange' was the very definition of an instant classic

The album debuted at No. 2 on the Billboard 200 and was nominated for album of the year at the Grammys. Spin praised the production's "loose, emptied-out glamour" and Ocean's wise lyricism; USA Today dubbed it the album of the year; Pitchfork bestowed an astonishingly rare high score of 9.5/10.

The New Yorker's Sasha Frere-Jones wisely noted that "Channel Orange" is not "just another album," and compared its rapturous reception to reading scripture.

Hua Hsa, an associate professor of English at Vassar College and staff writer at the New Yorker, favorably reviewed the album for Slate. He told Insider he remembers feeling "surprised at how universally beloved it was."

"Nowadays, it can seem like a consensus forms within the first half-hour of something being released," Hsa said. "At the time, it was interesting to me how passionately people loved it, and for so many different reasons."

Sonically, the album exists on its own plane

"Channel Orange" is extraordinarily vivid and thematically restless. No two of its 17 songs sound alike - and yet the tracklist is incredibly cohesive, threaded together by its cinematic motif.

The album opens with a 46-second intro titled "Start." You hear the muffled voices of two boys and the original iPhone text tone, filtered and opaque like a grainy home movie.

Then, you hear the sound of an old TV turning on, a PlayStation booting up, and the menu music from "Street Fighter II."

The album is sprinkled with similar sound effects and, as the title suggests, evokes the experience of flipping through channels.

A young couple is thrust into parenthood on "Sierra Leone," an addict struggles with disappointing his family on "Crack Rock," and the three-song stretch of "Sweet Life," "Not Just Money," and "Super Rich Kids" plays like a modern, Los Angeles-based coming-of-age take on "The Great Gatsby."

While Ocean's vivid storytelling captures many varied characters and scenes, each story maintains a sense of emotional intimacy.

Much of Ocean's songwriting feels very personal, and "Channel Orange" explores the intersection of fantasy and reality, of love lost and love still felt; his memories and his imaginative excursions blend together, building his own world in the microscopic in-between spaces.

Indeed, "Channel Orange" wasn't ahead of its time so much as it exists within its own timeline. The album is certainly indebted to Ocean's extensive knowledge of music history - drawing melodies and lyrical inspiration from titans like Prince, Elton John, Marvin Gaye, Mary J, Blige, and George Strait - but it's also firmly anti-traditionalist.

"Pyramids" makes that straddle explicit, drawing a clear line from the Ancient Egyptian Queen Cleopatra to a modern-day stripper.

The song is a sprawling, slow-burning, time-traveling voyage that doubles as a middle finger to his label and to radio gatekeepers. (Upon its release, Ocean tweeted, "Pyramids is a ten minute long single. I trolled the music industry.")

Put simply, "Channel Orange" is not easily described. It's packed with double meanings, contradictions, elaborate narratives, and kaleidoscopic details.

Even on songs with typical songwriting structures, like "Thinkin Bout You" or "Lost," the music itself doesn't conform to easy labels or genres. In terms of both production and lyricism, "Channel Orange" is the child of modernity, fluidity, and impossibly keen perception.

It has proven instructive for artists striving to be innovators, storytellers, and rulebreakers in an industry that rewards simplicity

Naturally, critics at the time took note of Ocean's assorted stylistic feast, nodding to the album's many flavors.

Rolling Stone praised Ocean's "distinctive voice" and cited hints of "Seventies funk, Eighties electro, and moody, downtempo hip-hop." USA Today described a fusion of "neo-soul, hip-hop, electro-pop, jazz-funk and psychedelic."

At the same time, these critics grasped at straws, describing "Channel Orange" as a branch of R&B and comparing Ocean to artists like The Weeknd and Miguel.

Eight years later, in a world that feels more comfortable forgoing definitions and labels, these comparisons feel very weak. We still haven't heard anything quite like "Channel Orange," and it's unlikely that we ever will. It is the truest definition of incomparable; it has no genre, no peer.

But that's not to say it didn't cause lasting, tangible ripples. In fact, there are shades of "Channel Orange" in the vast majority of the albums that we've fawned over in the past few years.

Ocean's imitators don't sound similar; they feel similar, following Ocean's blueprint of interior logic and genre-blending experimentation.

Acclaimed albums like Lorde's "Melodrama," Ariana Grande's "Sweetener," Tyler, the Creator's "Igor," and Billie Eilish's "When We All Fall Asleep, Where Do We Go?" are iconic because they defy convention and expectations. They create worlds unto themselves, and they don't fit quite right in any traditional category.

We've also seen this post-genre approach saturate radio and singles charts, as with Lil Nas X's smash hit "Old Town Road," which confounded music gatekeepers by straddling multiple musical styles with apparent ease.

"In a way, I think the sonic stuff that made 'Channel Orange' so arresting back then has really become a feature of mainstream pop music. Everyone's trying to sound a bit weird, or embody a kind of fluidity of perspective and genre," Hsa told Insider.

"But few have managed to capture Frank's point of view and eye for detail."

Whether these artists have been directly inspired by "Channel Orange" is irrelevant (even though, ahem, they have been). We can clearly see the album's release and success as paradigm-shifting moments in music history. The album's uniqueness, its refusal to be digested easily, flows through the current of popular music today.

"'Channel Orange' makes a listener recoil, for a moment, and think about how pop works, and what it is capable of," Frere-Jones wrote, eight whole years ago.

"Whatever Ocean is paying attention to, we are paying attention to. The album format was supposed to be dead, the market for music was supposed to be dead, and yet here we are now."

'Channel Orange' changed everything for queer artists

Of course, there have been many albums throughout history that influence other artists, affect music trends, and seem to exert their own gravitational pulls. Recent, pre-Ocean examples include Kanye West's "808s & Heartbreak" and Drake's "Take Care."

But the distinctive influence of "Channel Orange" has as much to do with Ocean's biography as it does his talent and ingenuity.

Any examination of this seminal work would be incomplete without acknowledging its queerness, as well as the landscape in which "Channel Orange" arrived.

One week before the album was released, on July 4 - aka Independence Day, perhaps not coincidentally - Ocean posted a thank-you letter on Tumblr. He described the summer when he fell in love for the first time, writing, "I was 19 years old. He was too."

"Back then, my mind would wander to the women I had been with, the ones I cared for and thought I was in love with," he wrote. "I reminisced about the sentimental songs I enjoyed when I was a teenager.. The ones I played when I experienced a girlfriend for the first time. I realized they were written in a language I did not yet speak."

"I don't know what happens now, and that's alrite. I don't have any secrets I need kept anymore."

The letter was originally meant to be included in the album's liner notes, but there had been whispers about Ocean's sexuality. A journalist who attended a "Channel Orange" listening party had taken note of the lyrics in "Forrest Gump" and "Bad Religion," which are both addressed to a male love interest.

So, it seems, Ocean decided to reclaim his own narrative.

"We talk about cultural resets, right? 'Channel Orange' was the cultural reset," Billboard contributor Glendon Francis, who identifies as queer, told Insider.

"I feel as though there's this model, within queer people's minds - we feel as though we have to do the work first and remain veiled or somewhat closeted, and then we can share to the world who we are. Because to do so before would block our blessings," Francis said. "We tend to have a certain fear where if we associate queerness with everything that we create, that there's a negative connotation of queerness, so there's a negative associated with our art."

"What Frank did was the total opposite," he continued. "He was like, "Here's who I am. Now enjoy this project because here's all the fruits of my loin, my labor of love, and I want you to know that when you are ingesting this, I exist, and many people like me exist.'"

The reverent reaction to "Channel Orange" becomes far more profound when you consider this context.

For "Thinkin Bout You" to climb the charts after Ocean clarified its queerness, for "Bad Religion" to receive such critical praise when there were so few Black, male, openly queer artists to speak of - three years before same-sex marriage was even legalized in the U.S. - is nothing short of historic.

Today, we have Lil Nas X, ILoveMakonnen, Kevin Abstract, and Ocean's own friend Tyler, the Creator - not to mention women of color like Kehlani, Janelle Monáe, Syd, Halsey, and Young M.A - who either came out in pivotal moments of their careers or before their careers had taken off, making queerness an essential aspect of their art.

In many ways, Ocean made that possible. As singer-songwriter Iman Jordan told the Los Angeles Times, "Frank Ocean was the beginning of the revolution."

To have his coming-out letter baked into the foundation of "Channel Orange," Ocean guaranteed that anyone who enjoyed his music would need to see him as a whole, complex person. He ensured that any fan who felt uncomfortable with his disclosure would need to confront that homophobia, and he cultivated a more spacious and accepting environment for other artists.

Hsa told Insider that he believes "Channel Orange" played a major role in how queerness in music has become more visible and accepted, particularly in spaces related to hip-hop and R&B.

"I definitely think Frank is someone who's been enormously influential and inspirational to a few different generations, and a lot of that has to do how comfortable he seems in his own skin, or his comfort with discomfort," Hsa said.

"He seems like someone who's always learning and taking in new information, and as a result, he's one of the few stars who also feels like they are growing and evolving on their own terms."

Francis agreed, and said that "Channel Orange" is to queer artists and music critics as a foundational, educational text is to activists.

"I have been writing about a lot of queer artists who are climbing their way towards mainstream success, and many have been very intentional with their personal stories," he said.

"A lot of them, if not all, are babies of Frank Ocean."