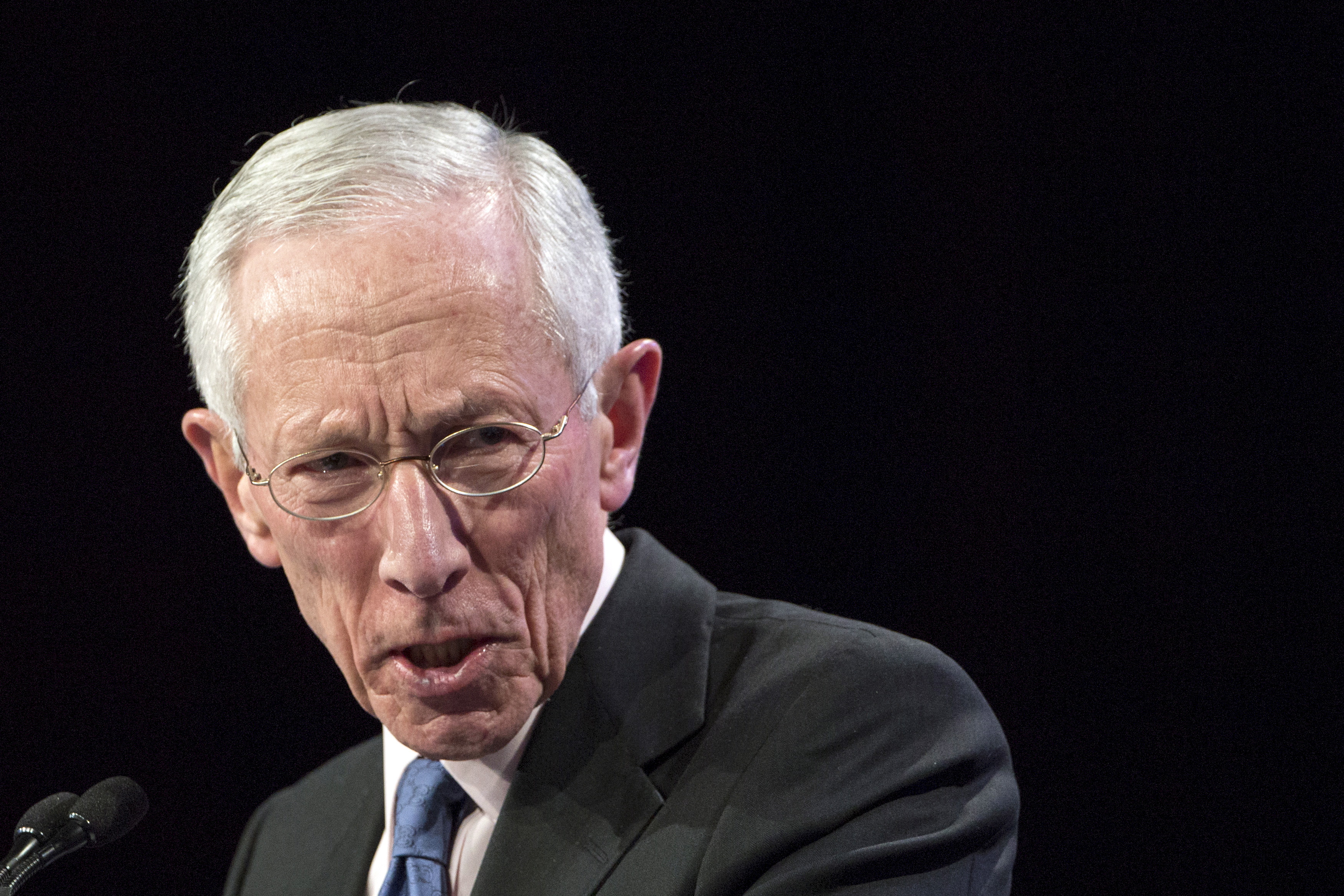

On March 23, Federal Reserve Vice Chair Stanley Fischer was the keynote speaker at a Brookings Institution dinner in Washington, DC.

There, he gave prepared remarks on regulatory policy and the Fed’s response to the financial crisis, and he took questions from the audience on the highly market-sensitive topic of interest-rate policy.

Federal Reserve officials give speeches all the time. What makes this one notable is that it was closed to the public, Fischer’s prepared comments have not been made available, and the fact the speech took place at all was not widely known.

It also came just days before another Fed official, Jeffrey Lacker, abruptly resigned as the Richmond Fed president after admitting that he played a role in a 2012 leak of market-sensitive details of the central bank’s internal deliberation. That leak, which arguably damaged the Fed’s credibility, was to a private consultant that then shared the details with clients who stood to net millions in profits by trading ahead of the release of news.

As Lacker’s resignation shows, it’s a scandal that continues to haunt the Fed. It doesn’t, however, seem to have discouraged the central bank from letting officials speak in private settings in which only a small group of people can glean insight from their comments.

Fischer's participation and the nature of his comments were described to me by two conference participants. The Federal Reserve declined to comment for this story.

"There is always a dinner speaker who is off the record and reporters are not ever invited," Brookings Institution spokeswoman DJ Nordquist said of the conference, which is an annual event.

Market-moving events

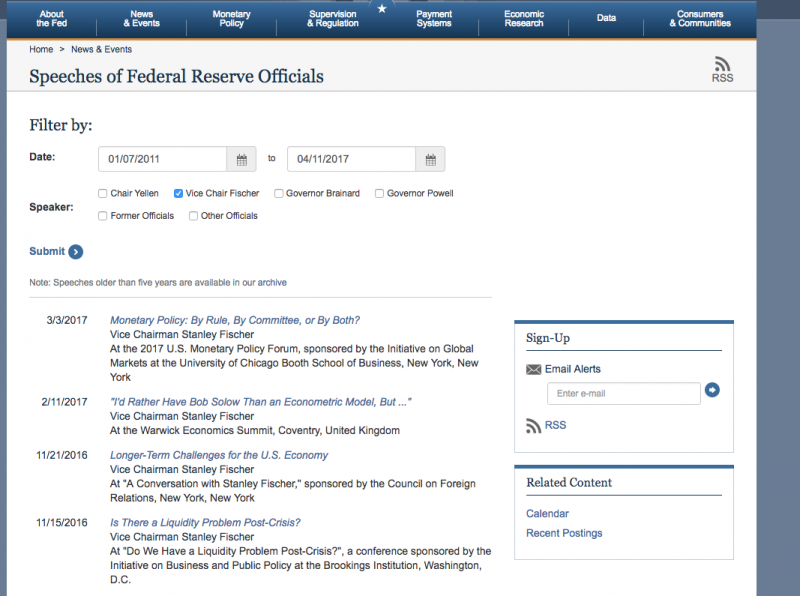

I don't know exactly what Fischer said, in part because the Fed hasn't put his comments up on its website as it does with other speeches.

But Fed actions are some of the most market-moving events in the world. Small pronouncements from a single official, especially one of Fischer's inner-circle status, can have deep consequences in stock, bond, foreign exchange, and other markets around the world. For that reason, every small nonpublic insight a trader or banker can acquire from the Fed has massive potential value.

This means Fed officials should not be speaking in private in the first place, especially since the practice appears to violate the central bank's own code of conduct for participants of the policy-setting Federal Open Market Committee.

The rules, drafted in response to a Reuters report on a separate leak in 2010, specifically say: "To the fullest extent possible, Committee participants will refrain from describing their personal views about monetary policy in any meeting or conversation with any individual, firm, or organization who could profit financially from acquiring that information unless those views have already been expressed in their public communications."

Fischer may not have said anything that would have immediately moved markets. But his very presence and willingness to take questions from financial-sector executives out of view of the media speaks to the kind of secrecy that the central bank portends to be countering with a transparency push that began under its former chair Ben Bernanke and that has continued under Janet Yellen.

True, Brookings is a nonprofit institution, not a bank. But its donors, the ones who get to attend exclusive-access dinners, include Wall Street megabanks. Its board of trustees includes two of the largest private-equity investors in the world - Carlyle Group cofounder David Rubenstein and Glenn Hutchins, a cofounder of Silver Lake - as well as high-level executives at Goldman Sachs, Deutsche Bank, and JPMorgan.

The 2012 leak, to Medley Global Advisors, raised new questions since his letter of resignation indicated he merely confirmed information that was already in Medley's possession, suggesting at least one other leaker. And the Fed's initial response was to paper over the issue with a toothless internal investigation, which was eventually taken over by the FBI and a congressional committee.

But what Fischer's speech last month shows is that the Fed has yet to grapple with the opaque practices that lead to situations like this in the first place. When it comes to speaking in private to money-people, there's only one thing left for Fed officials to do: Just stop.