- High inflation is usually associated with a strong job market, and vice versa. The pandemic changed that.

- Prices are soaring at a historic pace, yet labor force participation hasn't rebounded as expected.

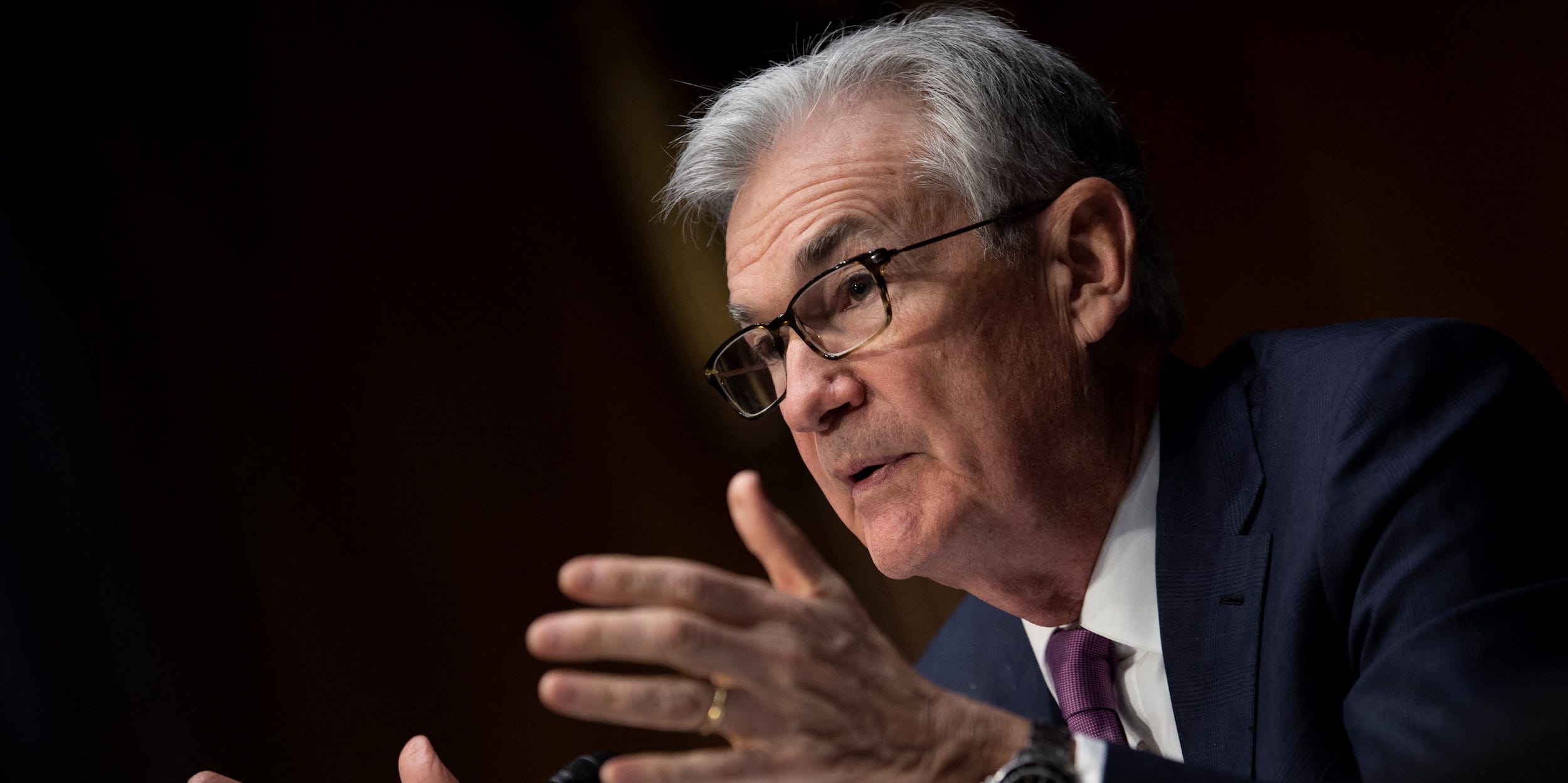

- The trend is a "rare occurrence" and places the US in an awkward spot, Fed Chair Jerome Powell said.

The pandemic threw several economic assumptions out of wack. Count the Phillips Curve — one of economics' most widely accepted concepts — among them.

The rule goes like this: unemployment and inflation have an inverse relationship, meaning inflation is low when unemployment is high, and vice versa. The rule is a guiding light for the Federal Reserve, which is tasked with balancing price stability with maximum employment in the US. It's helped the central bank determine when to slash rates to stimulate the economy and when to hike them to cool inflation.

The coronavirus recession threw a wrench in that relationship, Fed Chair Jerome Powell said Tuesday. Labor force participation is far from fully recovered as millions of Americans remain on the job market's sidelines. Yet inflation is running at its fastest rate in nearly four decades. The situation has complicated the Fed's mission and forced it to temporarily prioritize one goal over the other.

"Most of the time, monetary policy works the same way for both [mandates]," Powell told the Senate Banking Committee during his confirmation hearing, observing that for much of the last decade, low interest rates have supported both employment growth and pushing persistently low inflation up towards the central bank's 2% target. "In rare occasions though, you have a situation where the two goals are not complementary, and we've had a little bit of that here."

Powell added that he's "not sure" if the disconnect still exists, but the latest economic data suggests it's going strong. The labor force participation rate was flat in December, disappointing hopes that more people would return to the job search. The US is still down some 3.6 million nonfarm payrolls compared to pre-pandemic levels. The unemployment rate might sit near record lows, but other data clearly show the labor market is far from fully healed.

Meanwhile, the first December inflation data isn't due until Wednesday morning, but economists generally expect price growth to accelerate again to a 7% year-over-year pace. The disconnect between labor-market health and inflation appears alive and well.

The central bank's latest actions signal show its focus shifting to fighting the price surge. The Federal Open Market Committee announced in December it would double the pace at which it shrinks its emergency asset purchases. The move points to the purchase program now ending in March and opening the door to further normalization of monetary policy. Powell noted that, unless the virus situation dramatically changes, it's highly likely the central bank will raise interest rates multiple times in 2022.

Prioritizing the inflation mandate over directly supporting employment is key to bringing about a balanced recovery, and could even help create a more robust labor market in the long run, Powell said. High inflation is "a severe threat" to the Fed's maximum employment target, as it could force businesses to slow their growth and curb their hiring plans, according to the chair.

"To get the kind of very strong labor market we want with high participation, it's going to take a long expansion. We can see that participation is moving only very slowly, and to get a long expansion, we're going to need price stability," Powell added.

That outlook goes against the basic tenets of the Phillips Curve. The decades-old rule suggests a stronger labor market would go hand-in-hand with higher inflation. In hinting at the Fed's coming rate hikes, Powell is arguing inflation has to move lower for the labor market to fully heal.

Many factors needed to fight inflation are completely out of the Fed's hands. The price hikes seen throughout 2021 were fueled by massive consumer demand and hampered supply due to global shipping bottlenecks. Powell reiterated his forecast that the supply-side pressures will fade throughout 2022, saying the Fed could expect "some help" as supply chains heal.