- Facebook’s ad-targeting engine allows marketers to target people by a number of political triggers. They could be used by governments, political parties, or others looking to sway opinions or stir up divisions. Business Insider has not seen ads of this nature, but moving forward, experts say, Facebook must become more transparent about how its ad categories are generated and how people are grouped into them. Facebook says it has put safeguards in place to ensure that categories aren’t misused and the politically sensitive interest segments don’t violate the company’s standards.

Ever since Facebook acknowledged that Russian operatives meddled in last year’s presidential election by targeting ads to narrow interest groups based on divisive issues like race and immigration, the social network has promised to build in safeguards to ensure that postings on sensitive issues receive human scrutiny.

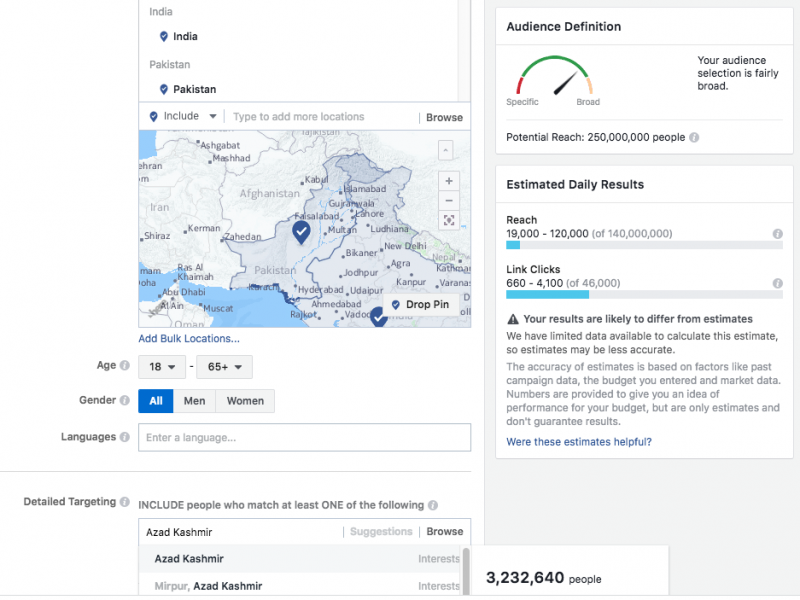

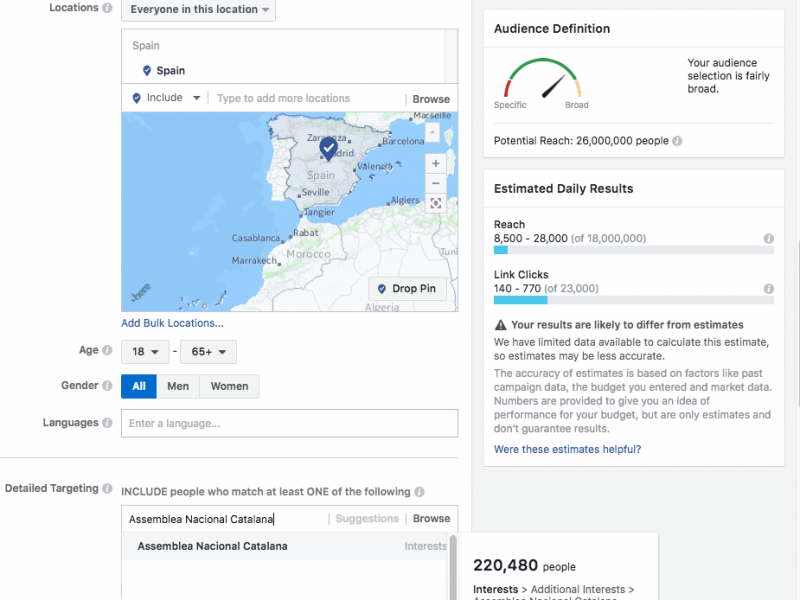

The safeguards are meant to help screen out ads making use of overtly hateful categories like “Jew Haters,” which was tested by ProPublica as a real filter for a hypothetical advertiser that made it past computer screening. A scan for other, albeit less inflammatory filters, shows that the social network still has its work cut out for it – around the world. Consider: As of Monday, a prospective advertiser could type the keywords “Azad Kashmir” or “Free Kashmir” in the “Detailed Targeting” section of Facebook’s ad targeting system and deliver ads to a potential audience of over 3.2 million people between the ages of 18 and 65-plus, respectively, across India and Pakistan, according to a test by Business Insider. Kashmir is the hotly disputed territory between the two countries. Similarly, ads targeting the words “Free Palestine” revealed the potential to reach over 1.8 million users in 21 different Arab countries, barring Syria, and Assemblea Nacional Catalana (of the Catalan National Assembly, which is leading the movement for Catalonia to secede from Spain) could reach 220,000 people.

A structural, fundamentally global problem

These ad categories, called interest segments, are by themselves simply identifiers of people interested in certain topics, such as Palestinian statehood or the India-Pakistan conflict. To be clear, Business Insider hasn’t seen any ads on the subject. But all three of these issues have also led to or inspired civil strife, violence, terrorism or warfare, and the issue Facebook has to contend with is that the targeting mechanisms can be misused to stir up divisions or promote disharmony. As in the case of Russian interference in US elections, it doesn’t take much for small amounts to go a long way as far as reach and engagement on the platform are concerned.

“This is not a one-off problem directly linked only to one political campaign,” said Taylor Owen, assistant professor of digital media and global affairs at the University of British Columbia and a senior fellow at the Tow Center for Digital Journalism at Columbia University. “Facebook has a structural problem and, fundamentally, a global problem.”

Facebook is working on checks and balances aimed at addressing overtly problematic interest segments. But the social networking giant still contains a large swath of ad targeting options, including the above, that lie in the gray zone and can be misused if backed by the wrong intentions.

Violence in Kashmir

Take Kashmir, for example. The region of Jammu and Kashmir has been a thorny issue between the two countries since they gained independence from Great Britain in 1947.

Over the past seven decades, the two sides have fought three full-blown wars and one smaller war over the region, which is half administered by India and half by Pakistan.

In the 1990s, Pakistan backed a guerrilla insurgency in Indian Kashmir, with both countries alleging that state-sponsored groups continue to cause unrest in their respective parts till this day.

In short, it is a highly charged and hot-button geopolitical issue. And it's entirely possible that extremist elements could take advantage of Facebook's tools to attempt to spread propaganda and aggravate the situation.

"Nefarious elements, if they wanted, could presumably veer into the Russian-style of fake news spreading and ad targeting, using even more subtle issues and topics to influence the other side," said Shailesh Kumar, a senior analyst at Eurasia, who analyzes political and economic risks and developments in South Asia.

Kumar also analyzed some of the pages associated with the issue, including many pages linked to Azad Kashmir (Independent Kashmir) - the name used by Pakistan for the part of Kashmir it administers. According to him, many of these are replete with images of extremists wielding weapons or photos of people allegedly killed by Indian authorities, which are "definitely divisive and driven by a clear agenda."

"This is far more than just a US problem," Sara M. Watson, a technology critic and an affiliate at the Berkman Klein Center for Internet and Society at Harvard University, told Business Insider in an interview. "The combination of personalization and microtargeting on Facebook can make for several morally ambiguous categories which can be used as proxies for more sensitive issues."

How interest segments are created and regulated

According to a Facebook representative, such politically sensitive interest segments don't violate the company's standards and that targeting could be done legitimately. For instance, Azad Kashmir could be used as an interest segment by an advocacy or issues-based group or a news outlet looking to promote a documentary film on the topic.

And Facebook added that it had put several safeguards in place to ensure that they weren't being misused. When it announced its handover of the Russian ads, the company said it would automatically send certain types of campaigns through an additional human review-and-approval process, if they included social, political, or religious interests. According to the company representative, the interest-segments part of this story were "likely a part of" that list.

The company also explained how the "detailed targeting" section is created, saying that the categories in the section comprise interest segments, which the company creates, and 5,000 self-reported interests, which have been reviewed after the ProPublica investigation.

As for the audience that is pulled in for the interest segments, as The New York Times reported, users sort themselves into categories by liking and visiting pages on Facebook, and a variety of other activities they engage in on the network.

If, for example, Facebook creates an interest segment around Mediterranean food, people who engage with Facebook pages related to the topic are likely to be included in the target audience associated with the segment. Advertisers, such as cookbook publishers in this case, can push their messages to those users.

Exploitative microtargeting

But the system is far from perfect. After Russian troll farms placed ads on polarizing topics like race and immigration, Facebook said it would block ads that included overtly racist content or directed users to a webpage promoting racist ideas. Despite oversight, and the checks and measures outlined above, Facebook continues to falter.

This week, a Bloomberg investigation revealed the company worked with the conservative nonprofit group Secure America Now to showcase ads that contained anti-Islam rhetoric. This was not just evidently hateful, but also can't be explained away as an algorithm glitch.

As Business Insider's Steve Kovach wrote, the issue goes beyond the question of whether or not political ads need to be regulated on tech platforms. Tech companies, including both Facebook and Google, need to be more transparent about political advertising on their platforms.

Transparency is the problem, said Watson.

Detailing her concerns in an op-ed for The Washington Post, Watson argues that Facebook allows for exploitative microtargeting. Facebook's personalization and categorization are largely based on inferring your likes, dislikes, and inclinations based on an algorithm, which it doesn't outline in any detail.

This is problematic, she wrote, as people have no idea what inputs actually go into their personalized feeds or determine the categories they become a part of. (Facebook says people can control the ads that they see and the interests that they're a part of through Ads Preferences.)

"The big question is, why are some of these morally ambiguous categories allowed to exist?" she told Business Insider. "Why can they be monetized at all? They are clearly there because there is some potential financial gain."

Facebook cannot keep ducking for cover and blame everything on algorithms. And that's because it has no choice, said Owen.

"Facebook does not want to regulate and determine what is acceptable beyond the most extreme cases because it is not in their commercial interest," he said. "And the governments, who have traditionally had regulation in their domain, don't have the tools to do so.

"Because of this huge disconnect, it is an unprecedented and complex global issue."