As details of the bomb blast at an Ariana Grande concert in Manchester, England, on May 22 and then of the knife and truck attack in London on Saturday night started flooding social media, one thing was noticeably absent from Facebook: solidarity filters.

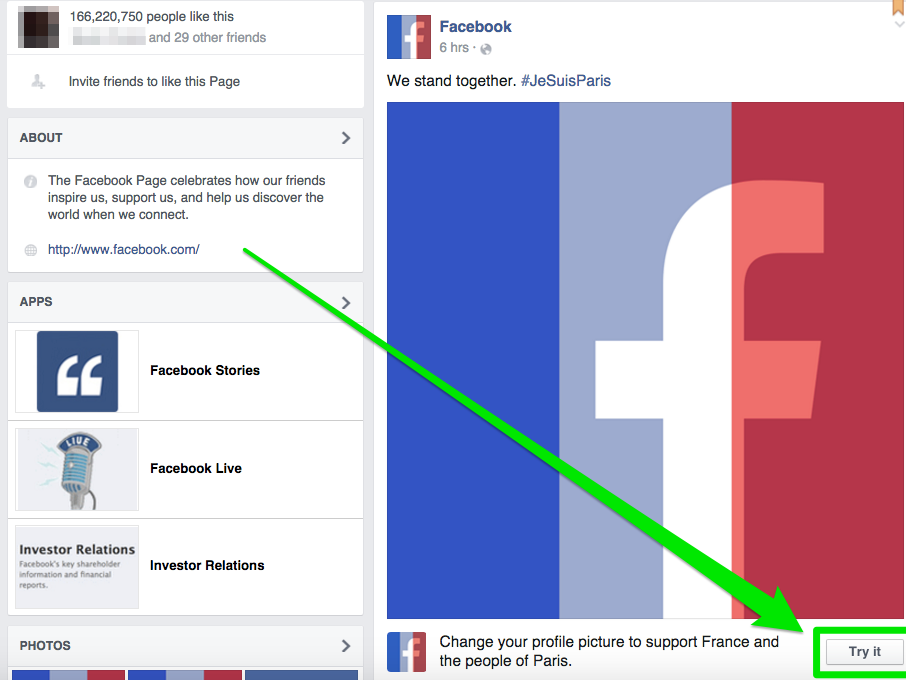

The filters, which let users lay a translucent flag of an attacked country over their profile picture, were first introduced by Facebook after the coordinated bombings and shootings in Paris that left more than 130 people dead in November 2015.

Along with the #prayforparis and #jesuisparis hashtags, the solidarity gesture quickly picked up speed – more than 120 million people used the French flag overlay in the first three days, a Facebook representative told Business Insider.

But Facebook’s swift decision to promote the solidarity gesture generated backlash in the form of sharp criticism from many who pointed out the lack of such compassionate gestures for crises in Lebanon and Syria. Facebook hasn’t promoted a solidarity filter since, the Facebook representative said.

The community response to the French flag filter led Facebook to rethink its strategy on promoting solidarity causes, the representative said, feeding an anxiety that the company may appear to be ranking the importance of human suffering depending on which events generated filters and which didn’t.

Facebook's "Safety Check" feature has received similar criticism, much of which has been mitigated by the company's decision to turn over activating the feature to a third party.

In April, Facebook took a new tactic with filters, introducing the new Camera Effects platform, which allows users to create their own frames and flag overlays. The platform also offers the frame-browsing option, in which people can pick from popular "cause" frames created by others.

Facebook is promoting Camera Effects as a way for individuals to use their own flag filters to "express support and unify behind the causes and movements they care about" rather than causes that are deemed important by others, the representative said.

Users have created filters and temporary profile pictures for major terrorist attacks over the past year, including a heart with a Union Jack for the Manchester attack and a "We Stand With London" frame following the London attacks.

But no one user-generated solidarity image or frame has, according to the Facebook rep, matched the millions of people who changed to a filter that has been promoted by the site (such as the 26 million who used the rainbow flag overlay that Facebook promoted after the Supreme Court ruled to legalize same-sex marriage across the US in June 2015). The only crowdsourced frame to come close was a Mother's Day frame created by user Susan G. Komen last year that was used by more than 24 million people.

Some observers have suggested that Facebook's decision to not offer official solidarity filters has been mirrored by lessening user interest in changing their profile picture as a whole for major events. While Facebook's promotion contributed to the popularity of certain filters, the frequency of terrorist attacks has also made it difficult for users to respond to each one.

"That shock meant people want to do something and doing something on Facebook meant putting a French flag on your Facebook picture," Jon Worth, a Berlin-based political blogger who writes often about digital solidarity movements, told Business Insider in an email. "But since then the incidents have come thick and fast - and while each loss of life is indeed a tragedy, the repetitive nature of these attacks in Europe has left people jaundiced."

The popularity of Facebook filters also tends to function in a cycle - a 2015 study found that people were more likely to change their Facebook profile in support of a cause after they saw eight other friends do so first.

Artist Tom Galle, who cocreated All Flags, an overlay filter of numerous flags made in response to what he and his partners felt was selective compassion after the Paris attacks of 2015, told Business Insider that while people still asked him to add different flags after new terrorist attacks, he had observed a general decline in what he calls "group solidarity" posts.

"I do think it is time to move on to other forms of internet activism that have more effect," Galle said. "A problem I notice is that in a lot of cases people refuse to look at the big picture and think of ways to unite and attack the problem at its source."