Wilf Walsh, the CEO of Carpetright, couldn’t resist having a dig at online mattress retailer Eve Sleep at the Retail2020 conference in London this week.

“In my paper, I read about a mattress company that floated on AIM yesterday and raised £35 million, is now valued at £140 million, but last year made an EBITDA loss of £11 million,” Walsh said at Tuesday’s conference.

He paused for a beat, then delivered the punchline: “I don’t know if Diane Abbot is the CFO there.“

Walsh is not the only person in the retail industry to have raised their eyebrows. Eve’s sales were just £12 million last year and 2016 was only its second year of trading. The company’s AIM admission document shows it needed a £5 million cash injection just months before its float to keep it ticking over.

The document also has some other interesting stats. In the two years Eve has been operating, the company’s conversion rate – the percentage of people who actually make a purchase when they visit its website – has fallen from 0.9% to 0.6%. The average order value has fallen from £465 to £445 (down to £423 in the second half of 2016) and the cost of acquiring each customer has risen from £176 to £245. The company offers free returns of its mattresses for up to 100 days and 15% of sales are returned.

In short, costs are going up, order value is dipping, and there are a lot of returns to deal with, which eat into profits. The company says it doesn't expect to make any profits or dole out dividends for the foreseeable future.

Despite all this, Eve's shares began trading on AIM with a pop on Thursday, rising from their listing prive of 101p to 105.5p. What makes Eve a £140 million company?

It's not selling mattresses - it's selling 'sleep'

The answer is two-fold: first, investors seem to view the company more as a tech business than a retailer; and secondly, Eve can spin a good yarn.

On the first point, investors are primarily buying into Eve's growth story. While sales were just £12 million last year, that was a 355% jump on sales in its first year of trading. Investors seem to be mesmerised by this number, which is more reminiscent of a tech business than a bed retailer.

Eve's CEO and cofounder Jas Bagniewski used to work at Rocket Internet, the German startup factory known for creating fast-growing e-commerce businesses and Bagniewski has built Eve along these lines. Hyper growth, profits later.

Eve says revenues are on track for similar growth again this year. US rival Casper doubled sales to $200 million last year and says it could double sales again this year. Investors want a piece of that and no doubt hope that, like a tech business, Eve grows into its valuation.

On the second point, Eve has made the mattress market sexy. The company talks about selling beds and pillows as if it were Facebook, Uber, or Airbnb - not Dreams or John Lewis. Eve says in its prospectus that it wants to turn "a "sleepy" product category into a truly desirable one." With any luck, millennials will be Snapchatting their Eve mattresses before you know it.

This aspirational narrative also helps Eve paint a bigger picture for investors to imagine. The boring old bed market is worth £5 billion in the EU, £1 billion of which is in the UK.

But Eve isn't in the bed market. No, it's in the "sleep" market. This, Eve says, "is, by 2019, forecast to be worth approximately £26 billion in Europe, of which the UK is forecast to comprise approximately £6 billion." Eve plans to expand into everything from pyjamas to bedside tables.

Cut-throat competition

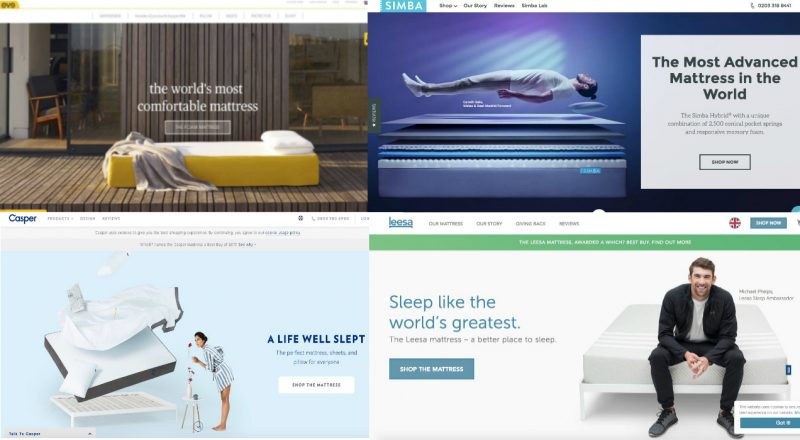

All of this is a high-risk bet for investors. Online mattresses have become one of the most competitive areas of retail in recent years. Across the US and UK, Tuft & Needle, Leesa, Eve, Simba and Casper are all trying to sell you their version of the world's best mattress.

All of these businesses have opened up in the last few years and do much the same thing - make and sell one mattress with perhaps a pillow and sheets. The mattresses tend to be relatively cheap - Eve's sells for £399 - and most come with a 100-day return guarantee.

Competition among these startups is cut-throat. Simba have enlisted Real Madrid football star Gareth Bale to help shift their mattresses. Leesa have US Olympic swimming legend Michael Phelps hawking their beds.

Every time I have written an article about Eve or one of its rivals I have been emailed by a PR company working for Simba asking if I would include a comment from its CEO, more or less just promoting its product. Casper offered an interview with its European chief after a piece about Eve. In short, they're all vying for attention.

This is all before you take into account traditional bed retailers like Dreams, Bensons for Beds, or department stores like John Lewis or Debenhams. Will they up their game in face of all this competition?

Eve admits in its prospectus: "The highly competitive nature of this market means that the Company is continually subject to the risk of (a) loss of (or failure to increase) market share, (b) reductions in margins and (c) the inability to secure new customers."

The solution? "The Company's aim is to become the leading pan-European sleep brand." Easier said than done. Eve and its rivals all seem to target millennials and young professionals and all, to the untrained eye, look remarkably similar.

Growth could be hard to sustain, too. Bedding is not like other many other markets, with a relatively low repeat customer rate. Eve guarantees its mattresses for 10 years. Spending £245 to get a customer to spend £423 with you once every 10 years doesn't seem like a great business and the idea that customers will return to buy pyjamas from the company they bought their bed from is far from proven.

Eve says in its prospectus that it is losing money and customer acquisition costs are going up simply because it is investing for growth.

"In the UK (the Company's most established market) eve's CPA [cost per acquisition] has started to decrease materially," Eve says, "and the Directors envisage that the UK business can break even in the near term. In the medium term, the Company's aspirational blended CPA target (for the UK) is around £100."

Ultimately, though, Eve will eventually have to show it can make a profit for investors, not just grow in size. This is something that Rocket Internet, Bagniewski's old shop, has struggled to do. Shares are trading well below their IPO price.

Eve promises profits in the unspecified "medium term." Investors will be hoping there's money to be found under its mattresses.