- SpaceX launched 60 more of its Starlink high-speed internet satellites into orbit on Wednesday, bringing its total fleet to about 480 spacecraft.

- Gwynne Shotwell, SpaceX’s president and COO, told Aviation Week the rocket company hopes to roll out service by the end of 2020 with about 800 satellites total.

- But CEO and founder Elon Musk believes perfecting user terminals – devices that will connect subscribers to Starlink – remains a significant hurdle in making Starlink profitable.

- “The fully considered cost of the user terminal is … the hardest challenge for Starlink,” Musk told Aviation Week, but added: “I think we’ve got a strategy where success is one of the possible outcomes.”

- Analysts say the lowest cost for one of the devices is about $1,200. Musk said cutting costs and making terminals last five to 10 years “will take us a few years to really solve.”

- Visit Business Insider’s homepage for more stories.

On Wednesday night, just a few days after rocketing its first NASA astronauts to space, SpaceX launched and deployed its seventh batch of internet-beaming Starlink satellites into orbit.

The mission slipped 60 of the desk-size spacecraft into low-Earth orbit, boosting the rocket company’s total fleet to more than 480 satellites (though some of these are experimental).

With any luck, SpaceX executives think they can bring online the floating high-speed network by the year’s end with about 800 total spacecraft.

“We hope to roll it out this year,” Gwynne Shotwell, SpaceX’s president and COO, told Aviation Week space editor Irene Klotz for an episode of Check Six, a podcast published by the magazine. “After the eighth launch, we’ll have continuous global coverage but not a ton of bandwidth.”

Over time, and with expansion to perhaps tens of thousands of thousands of satellites, global revenue from the project could top $50 billion annually, company founder Elon Musk has said.

But if that vision is to materialize, SpaceX first needs to roll out a user terminal, or "UFO on a stick" device, that can autonomously connect a subscriber to the satellites zooming overhead - and one that isn't too expensive to build, install, or maintain.

Therein lies what Musk recently said is Starlink's most significant hurdle to clear before it might establish a successful Starlink business.

"I think the biggest challenge will be with the user terminal, and getting the user terminal cost to be ... affordable," Musk told Aviation Week in a different episode of Check Six. "That that will take us a few years to really solve."

Starlink is rapidly building toward public internet service

Musk said in May 2019 that it will take about 400 satellites to establish "minor" internet coverage and 800 satellites for "moderate" or "significant operational" coverage around the world.

Making that network profitable, though, apparently requires a slightly higher number.

"For the system to be economically viable, it's really on the order of 1,000 satellites. If we're putting a lot more satellites than that in orbit, that's actually a very good thing, it means there's a lot of demand for the system," Musk told Business Insider in a press call on May 15, 2019, just ahead of the company's first Starlink launch, which sent a batch of 60 experimental satellites into orbit.

Shotwell noted the company needs to get to its 12th, 13th, or 14th launch to start providing service, or between 720 and 840 Starlink spacecraft.

"After we get 14 launches, we'll roll out service in a more public way," she said, adding the company will "probably do some beta rollouts before that."

SpaceX plans to launch 60 satellites every two weeks, with two more Starlink missions in the queue for June alone, according to a launch schedule maintained by Spaceflight Now. If that rate holds, the network may be operational in three to four months and profitable by the end of the year.

The user terminals may not be ready to support a full rollout, though.

A need for cheap and long-lasting ground antennas

It's not yet clear exactly how Starlink will work; the company has remained tight-lipped about the specifics.

However, Musk has explained the service is geared primarily toward serving rural and remote regions that fiber-optic cables and mobile towers struggle to reach. To get online, future subscribers will connect to the service using a device called a phased-array antenna, which Musk said in 2015 should cost around $200 each.

"Looks like a thin, flat, round UFO on a stick. Starlink Terminal has motors to self-adjust optimal angle to view sky," Musk tweeted in January, adding that all a user has to do is plug it in and point it upward. "These instructions work in either order. No training required."

The devices, which use transistors to rapidly track and communicate with in-view satellites, are necessary for Starlink because the spacecraft move overhead so quickly. Physical dishes that must be physically pointed, like those used to point at a stationary TV satellite, wouldn't suffice.

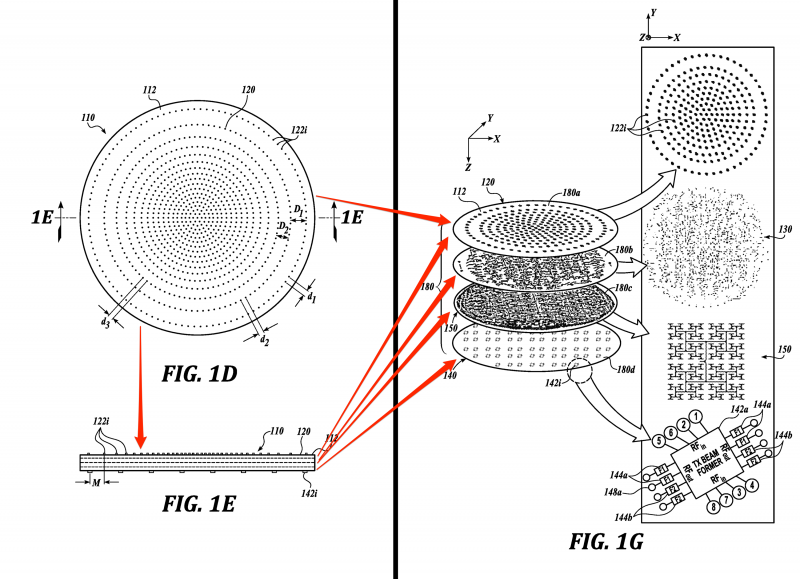

SpaceX in February 2018 filed US and world patents for a "distributed phase shifter array system and method." The US version is pending and the world version is still under review, so neither the US Patent Office or World Intellectual Property Organization has yet granted SpaceX a patent.

Industry analysts say phased-array devices today cost about 10 times as much as the price point Musk hopes to achieve. The CEO is also concerned about how long such devices could stand out in the open, year after year, without requiring service or replacement, since maintenance needs would drive up cost.

"The user terminal cost is as considering ... the fully installed cost. So the hardware, as well as everything required to get it set up and running, and running reliably for a decade or certainly at least five years-plus," he said. "You can't send people out to service these things, because a lot of places will be in the middle of nowhere."

'We are focusing on making it not go bankrupt'

Musk is also aware the path to high-speed satellite internet is littered with bankruptcy.

The most recent of which is OneWeb - a potential competitor that aims to launch thousands of satellites, yet declared bankruptcy in March. Most famously, though, there was Iridium: a constellation of 66 car-sized space satellites that was to create global wireless network for telephone and pager data.

Motorola fueled the company in the 1990s with roughly $5 billion in investments ($6 billion when adjusted for inflation). But shortly after it deployed around Earth, new subscriptions flatlined due to the steep price of the service.

"We need to set the stage of [low-Earth orbit] constellations. Guess how many LEO constellations didn't go bankrupt? Zero," Musk said at the Satellite 2020 conference in March, according to Via Satellite. "We are focusing on making it not go bankrupt."

If SpaceX can drive down the cost of phased-array user terminals - and quickly - it may be well-positioned to avoid similar hindrances to success. It could also handily beat Jeff Bezos' planned Project Kuiper satellite internet network to creating a profitable service.

In his conversation with Klotz of Aviation Week, Musk spoke with a mix of confidence and realism about the challenge.

"The secret to SpaceX's success is that we've got ... a better engineering team than I think has ever existed working on Starlink," Musk said. "I think we've got a strategy where success is one of the possible outcomes. ... That's high praise, because I think there's a lot of them where success was not one of the possible outcomes."