Sinaloa cartel chief Joaquín “El Chapo” Guzmán was bustled into the hands of US authorities in Ciudad Juarez early on Thursday evening, and before the end of the night he was on the ground in Long Island, being hustled to a detention center in New York City.

“As he deplaned, the most notorious criminal of modern times, as you looked into his eyes you could see the surprise, you could see the shock, and to a certain extent you could see the fear,” said Homeland Security Special Agent In Charge Angel Melendez.

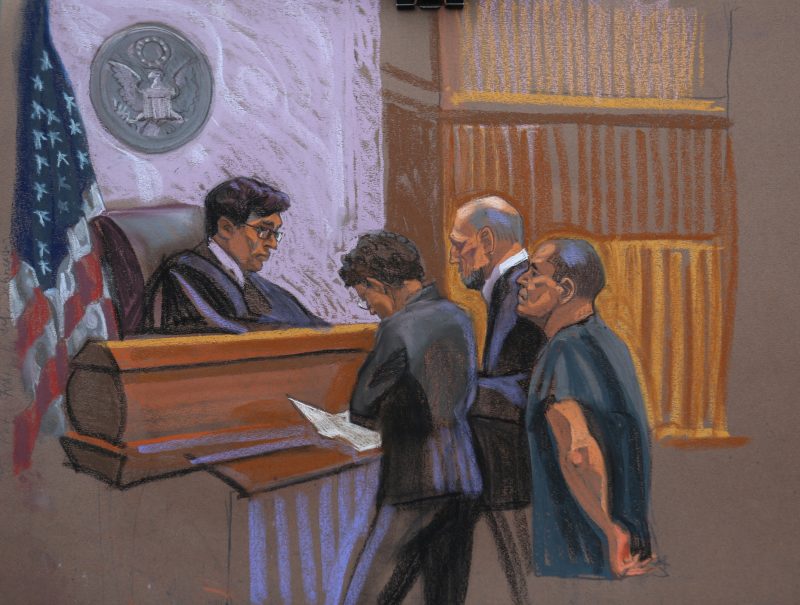

Guzmán appeared in a US federal court in Brooklyn on Friday, where the litany of charges filed against him by US prosecutors were made known to him – apparently for the first time.

After US Magistrate Judge James Orenstein asked if he understood the accusations against him, Guzmán responded through a Spanish interpreter, “Well, I didn’t know until now.”

Later, when asked again, Guzmán said he understood.

The Mexican cartel chief ultimately pleaded not guilty, and an additional hearing is slated for February 3.

The Eastern District of New York, based in Brooklyn, has filed a 17-count indictment against Guzmán, carrying a mandatory minimum sentence of life in prison.

"Who is Chapo Guzman? In short, he's a man known for no other life but a life of crime, violence, death and destruction, and now he'll have to answer to that," US Attorney for the Eastern District Robert Capers said.

"Guzmán's story is not one of a do-gooder, or a Robin Hood, or an escape artist," Capers added. Rather, "Guzmán's rise was akin to that of a small cancerous tumor that metastasized into a full-blown scourge."

Guzmán's lawyers have promised a zealous defense and said they would look into whether Guzmán was extradited appropriately.

"I haven't seen any evidence that indicates to me that Mr. Guzman's done anything wrong. Most of you probably haven't seen any evidence like that either," federal public defender Michael Schneider said outside the courthouse.

Prior to the heading, US prosecutors filed a 56-page memo arguing that Guzmán should be denied release while his trial is pending. The document also outlines some of the evidence US authorities will bring to bear during the case.

Here's the case the US government says it has against "El Chapo" Guzmán.

According to the filing, Guzmán emerged on the scene in the 1980s and 1990s, when Colombian traffickers still controlled production in their country and most of the distribution in the US.

"Guzman quickly set himself apart from other Mexican transporters with his efficiency in transporting the drugs into the United States, including to California, Arizona and Texas, and returning the drug proceeds to the Colombians in record time," the memo states.

As documented elsewhere, "This effectiveness earned him the nickname 'El Rapido.'"

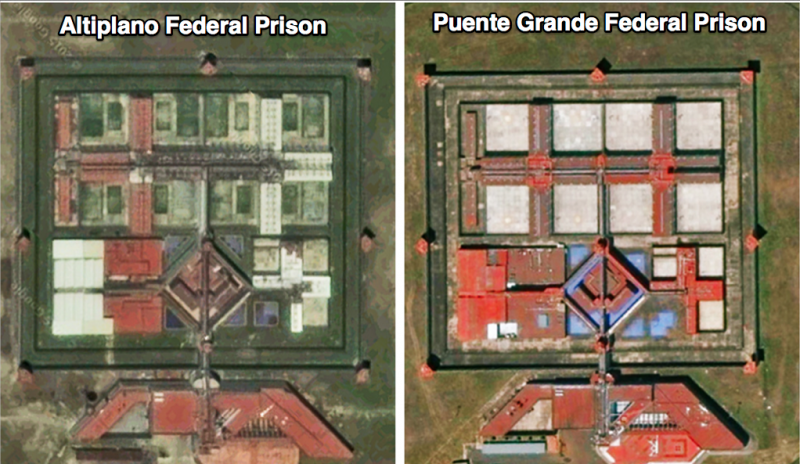

Guzmán and his partners in the Sinaloa cartel gained power during the late 1980s and 1990s, though he was eventually detained in Guatemala in 1993 after a series of high-profile clashes with rivals in Mexico. He was jailed at Puente Grande prison in southwest Mexico, though he maintained connections with his business partners during this time.

In 2001, with the help of bribed Mexican officials, he escaped from prison, returning to his home turf.

"To thwart law enforcement efforts to recapture him, he created an army of hundreds of heavily-armed body guards and fortified his hideaways with military-grade weapons," the memo says.

"Guzman also established a complex communications network to allow him to speak covertly with his growing empire without law enforcement detection," it adds. "This included the use of encrypted networks, multiple insulating layers of go-betweens and ever-changing methods of communicating with his workers."

During this period, Guzmán and the Sinaloa cartel were able to expand their operations in Mexico and abroad, typically through bloodshed. This expansion included ports on Mexico's Atlantic and Pacific coasts, as well as cities on the US-Mexico and Mexico-Guatemala borders.

"Guzman and members of the Sinaloa Cartel infiltrated other Central American countries, including Honduras, El Salvador, Costa Rica and Panama," the filing states.

Sinaloa cartel personnel in these areas moved drug shipments through ground methods like tractor-trailers, but also through air transport via clandestine landing strips and, eventually, in rudimentary semi-submersible vessels that could carry up to six tons of cocaine.

The Sinaloa cartel's reach didn't stop in Central America, however. According to US prosecutors:

"This expansion continued further south; whereas previously the Colombian Cartels were the only power brokers with the sources of supply, Guzman soon embedded Sinaloa Cartel members in South American source countries, including not only Colombia, but also Ecuador and Venezuela, to negotiate directly with traffickers in the supply chain."

In the 2000s, the growth of methamphetamines led Guzmán to establish "sources of supply for the precursor chemicals for the production of methamphetamine in Africa and Asia, including in China and India."

Guzmán's home turf in Sinaloa state has reportedly become a hotbed for synthetic-drug production.

According to US prosecutors, Guzmán bolstered and protected this supply and distribution network through violence and graft.

"A cornerstone of his strategy was the corruption of officials at every level of local, municipal, state, national and foreign government, who were paid cash bribes … These payments also ensured that Sinaloa Cartel members were protected from arrest and that territorial disputes were resolved in favor of the Cartel. For example, as much as one million dollars in cash bribes were paid to law enforcement to ensure the safe passage of a single drug shipment through Mexico."

"Guzman also employed 'sicarios,' or 'assassins,' who carried out thousands of acts of violence, including murders, assaults, kidnappings, torture and assassination at his direction, to promote and enhance his prestige, reputation and position within the Sinaloa Cartel and to protect the Cartel against challenges from rivals. Sicarios were deployed to silence potential witnesses and retaliate against anyone who provided assistance to law enforcement authorities against Sinaloa's interests."

Guzmán also sent these sicarios against rival cartels, particularly the Gulf and Los Zetas cartels, as well as the Juarez cartel in Ciudad Juarez, which is not only a major drug-transshipment point but also served as Guzmán's home for the months prior to his extradition.

"These sicarios kidnapped and tortured their victims often prior to brutally murdering them and subsequently boasted of their exploits through gruesome videos that they posted on the internet," US prosecutors state in their pretrial filing.

According to the US federal government, a number of cooperating witnesses, including Colombian cartel leaders, will testify "to prove Guzman's power, corruption and violence within the Sinaloa Cartel," as well as to the "astonishing illegal profits" reaped by Guzmán from his involvement in the drug trade.

Some of the US government's purported physical evidence against Guzmán includes "recovered drug ledgers from Colombian cartel bosses and suppliers, which detail the financial agreements between Guzman and the suppliers for various drug shipments."

Guzmán has been linked to high-profile Colombian traffickers - some with ties to Pablo Escobar and former President Alvaro Uribe - in the past.

Other witnesses will testify to the Sinaloa cartel's various drug-transportation methods, from tanker trucks to planes to tunnels, and to methods used to smuggle cash from drug sales back into Mexico.

"One former member of local law enforcement in Juarez, Mexico, is expected to testify to being paid hundreds of dollars per month to release from custody Sinaloa Cartel members who were arrested, remove road blocks from routes over which trucks containing drug shipments were traveling and provide armed escorts for the drug-laden trucks that were passing through their area," the memo states.

Other witnesses "will detail specific murders carried out under Guzman's orders, including that of Sinaloa Cartel members, members of rival cartels and also government and law enforcement officials."

Several witnesses is to testify to the specific wars fought by the Sinaloa cartel against the Arellano Felix Organization, Gulf cartel, Los Zetas cartel, the Juarez cartel, and the Beltran Leyva Organization.

One witnesses is expected to describe a house specifically outfitted for killing victims used during the fight with the Juarez cartel. "The house had plastic sheets over the walls to catch spouting blood and a drain in the floor to facilitate the draining of blood," the memo says.

The US government also intends to produce evidence related to weapons seizures, including "evidence of a seizure in El Paso, Texas, of a gun shipment tied to Guzman, which contained numerous AK-47s and .50mm long rifles."

"Guzman has known no other life than a life of crime and violence," the pretrial memo concludes. "Driven by insatiable power and greed, Guzman's personal history and characteristics demand detention to prevent him from being a danger to the community."

US prosecutors say they have more than 40 witnesses ready to testify against Guzmán in a trial likely to last "many" weeks.

Until that trial is concluded, Guzmán will remain locked up in a federal jail in New York City.

US officials have declined for security reasons to state where exactly he's being held, and they appear confident there will be no repeat of the escapes for which Guzmán has become known.

"I assure you, no tunnel will be built leading to his bathroom," Special Agent In Charge Melendez said after the hearing.

"What occurred in other countries will not occur here," added Capers.