- The US has been downgraded to a “flawed democracy” by the Economist Intelligence Unit. The downgrade reflects Americans’ drop in confidence in governmental institutions, according to the EIU. Americans’ trust in government has been declining since the late 1950s, according to data from Pew Research. Moreover, inequality in the US has been on the rise, according to data from Deutsche Bank and Goldman Sachs. Populist politicians have tapped into these trends, the EIU said.

The US has been downgraded to a “flawed democracy” from a “full democracy” by the Economist Intelligence Unit in its 2016 “Democracy Index” report.

Although the report’s publication comes shortly after the election of President Donald Trump, the EIU analysts write that the US was not downgraded because of him. Rather, they argue, his surprise election was an effect of the underlying causes that led the EIU to downgrade the US.

According to the EIU, “full democracies” are countries in which basic political freedoms and civil liberties are respected, and are “underpinned by a political culture conducive to the flourishing of democracy.” The government functions satisfactorily; media are independent and diverse; the judiciary is independent and their decisions are enforced; and there’s an effective system of checks and balances.

Meanwhile, “flawed democracies” have free and fair elections (with possibly some issues such as infringements on media freedom) and respect basic civil liberties. However, there are governance problems and low levels of political participation.

The US’s overall “Democracy Index” score fell from 8.05 in 2015 to 7.98 in 2016 – just below the EIU’s threshold of 8.00 for a “full democracy.” The analysts write that a key factor in the drop was Americans’ growing distrust in governmental institutions.

"Popular trust in government, elected representatives, and political parties has fallen to extremely low levels in the US. This has been a long-term trend and one that preceded the election of Mr. Trump as the US president in November 2016," they write.

"By tapping a deep strain of political disaffection with the functioning of democracy, Mr. Trump became a beneficiary of the low esteem in which US voters hold their government, elected representatives, and political parties, but he was not responsible for a problem that has had a long gestation."

Notably, they write that even if 2016 weren't an election year, the US's score would've dipped below 8.00.

"The thing that mainstream commentators said disqualified Mr Trump - his lack of political experience - was what qualified him in the view of so many who voted for him," the analysts wrote. "He appealed to the angry, anti-political mood of larges swathes of the electorate who feel that the two mainstream parties no longer speak for them."

As a reference point, other countries that qualify as "flawed democracies" and have similar scores on the EIU metrics as the US include Japan, Italy, France, South Korea, Israel, Estonia, India, and Chile.

Americans' trust in government has been declining since the late 1950s. And after an uptick from the mid-1990s to the early 2000s, confidence again dropped, according to Pew Research data cited by the EIU. In fact, the percentage of Americans who say they trust the government "just about always" or "most of the time" dropped to less than 20% in the mid-2010s.

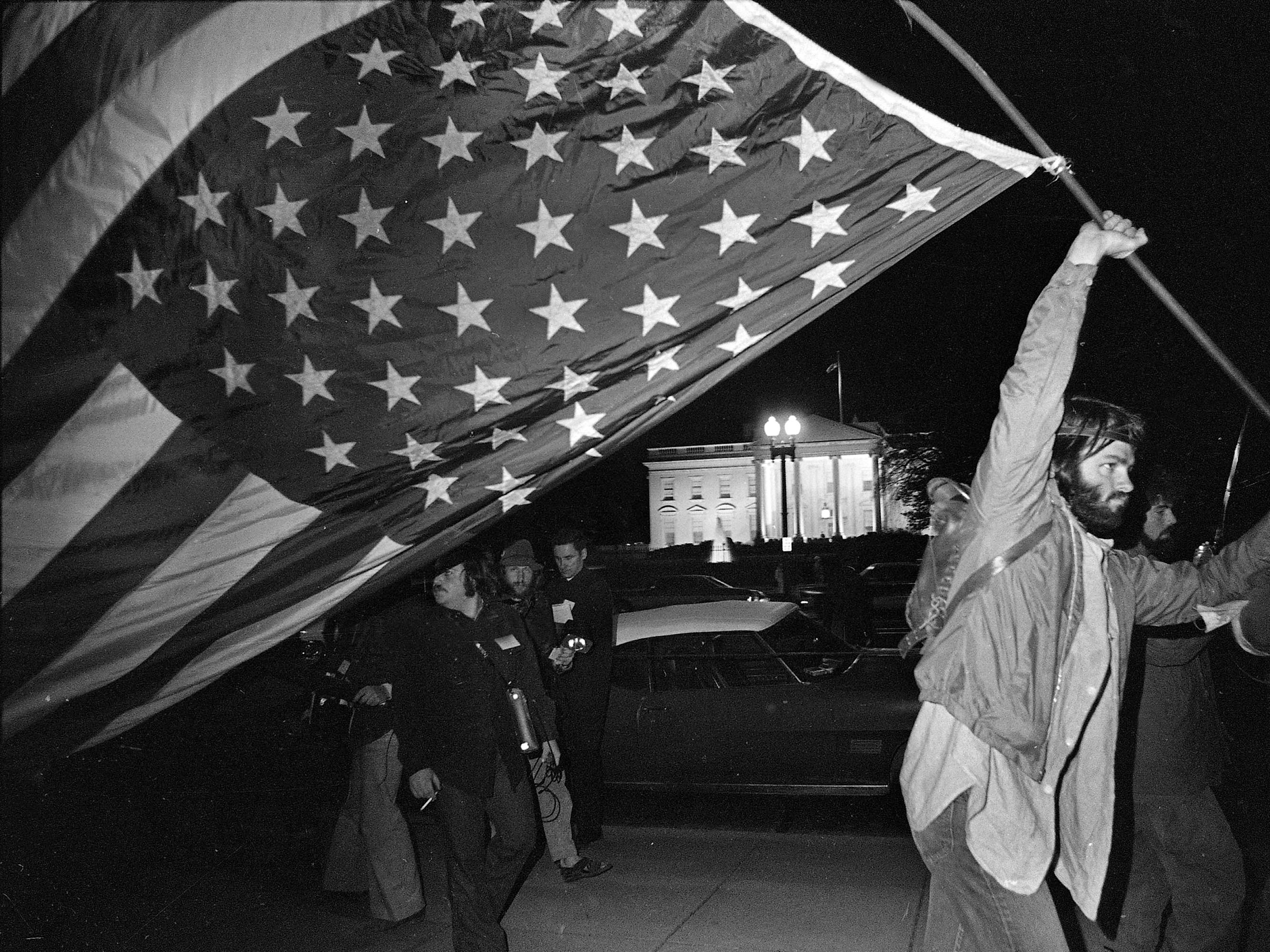

The EIU argues that there are several reasons for this decline. First, major political events over the past several decades, including the Vietnam War, the Watergate scandal, the Iraq War, the financial and housing crisis in 2008-2009, and government shutdowns, have eroded Americans' trust in government.

Additionally, the EIU argues that rising income inequality has been an underlying factor in growing distrust.

On that note, a few months back Deutsche Bank's chief international economist Torsten Sløk sent around a chart to clients showing the share of US household wealth by income level.

The takeaway? The top 0.1% of American households now hold about the same amount of wealth as the bottom 90%.

Moreover, the US happens to be a big outlier when it comes to inequality. In August, Goldman Sachs' Sumana Manohar and Hugo Scott-Gall shared a chart comparing a given country's gross domestic product per capita to its Gini coefficient.

The Gini coefficient is a measurement of the income distribution within a country that aims to show the gap between the rich and the poor. The number ranges from zero to one, with zero representing perfect equality (everyone has the same income) and one representing perfect inequality (one person earns the entire country's income and everyone else has nothing.) A higher Gini coefficient means greater inequality.

Developed market economies such as those in Germany, France, and Sweden tend to have a higher GDP per capita and lower Gini coefficients. On the flip side, emerging market economies in countries like Russia, Brazil, and South Africa tend to have a lower GDP per capita but a higher Gini coefficient.

However, the US's GDP per capita is on par with developed European countries like Switzerland and Norway, but its Gini coefficient is in the same tier as Russia's and China's.

"If income inequality has exacerbated American trust in government and public institutions, continued economic progress should start to reverse this trend in the coming years," they wrote. "The unemployment rate has fallen below 5%, average hourly wage growth is at its highest level since the financial crisis, and income inequality should gradually narrow if the economic recovery continues."

As for Europe

But the US is not the sole country to have a decline in confidence in political elites and institutions; major European economies have also seen this trend. In June, Britons voted to leave the EU in the Brexit vote, while populist movements have been on the rise across the continent.

"The populists are channeling disaffection from sections of society that have lost faith in the mainstream parties. They are filling a vacuum and mobilizing people on the basis of a populist, anti-elite message and are also appealing to people's hankering to be heard, to be represented, to have their views taken seriously," argued the EIU analysts in their report.

"Populist parties and politicians are often not especially coherent and often do not have convincing answers to the problems they purport to address, but they nevertheless pose a challenge to the political mainstream because they are connecting with people who believe the established parties no longer speak for them."

(As an aside on the "connecting with people" point, the EIU notes that Trump and his team "cleverly used social media, especially Twitter, to flatten the media and reach people directly.")

That being said, unlike for the US, post-Brexit UK is still a "full democracy" and its score increased - to 8.36 in 2016 from the prior year's reading of 8.31 - because of increased political participation with the Brexit vote.

The referendum drew a turnout of 72.2%, compared with average turnouts of 63% in the four general elections since 2001. "The long-term trend of declining political participation and growing cynicism about politics in the UK seemed to have been reversed," the analysts wrote. "There has also been a significant increase in membership of political parties over the past year."

In any case, the EIU team also argues in their report that both the election of Donald Trump and the Brexit vote should be taken seriously.

"The seismic nature of the Brexit and Trump victories should not be underestimated. Politics as we have known it for the past 70 years is not going to go back to 'normal,'" they argued. "The Brexit and Trump breakthroughs could add further fuel to the populist challenge to the mainstream parties that is evident across Europe."