- Former Department of Justice officials expressed alarm Friday at the DOJ’s decision to hand over former FBI Director James Comey’s memos to Congress, and their subsequent leak to the press.

- The significance of the memos’ release stems not from their content, but from the potential long-term implications regarding the DOJ’s independence.

- “If it weren’t so comical, it would be a tragedy,” said one former federal prosecutor.

The Department of Justice took the extraordinary step Thursday of sending evidence in an ongoing criminal investigation to Congress, which was leaked to the press hours later.

Patrick Cotter, a former federal prosecutor, described the situation bluntly: “This is freakishly unusual” and “unfortunate,” he said.

The evidence in question was a set of memos compiled by former FBI Director James Comey about his interactions with President Donald Trump. The documents constitute a central part of special counsel Robert Mueller’s obstruction of justice case against Trump.

The significance of the memos’ release stems not from the documents themselves, but from its long-term implications for the independence of the DOJ.

Much of the memos' substance was already public knowledge, and the documents will likely give a small advantage to the prosecution because they appear to be consistent with Comey's congressional testimony and public statements.

"The more consistent his statements turn out to be, the stronger a witness Comey will become," Cotter said.

Even then, "the memos are only relevant if what the president said at a certain meeting becomes the basis for a charge," said Jeffrey Cramer, a former federal prosecutor in Chicago.

But their release to Congress and subsequent leak was "awful," Cramer said. "If it wasn't so comical, it would be a tragedy."

Matt Miller, a former DOJ spokesman, said as much.

"This cave by DOJ will have long-lasting ramifications," he said. "This is an area governed solely by precedent, and DOJ is setting precedent that it is ok for Congress to interfere with, and receive documents pertaining to, active investigations."

Republican lawmakers said they were demanding the memos as part of their oversight responsibilities and because Congress also has several ongoing investigations into Russian interference in the 2016 election.

"Even to a blind man, it's apparent that these are political investigations that are not uncovering any new facts," Cramer said, adding that the move was "foolhardy."

'The DOJ may as well have delivered the memos to the media themselves'

The DOJ sent Comey's memos to Congress in response to demands from House Intelligence Committee chairman Devin Nunes, House Oversight Committee chairman Trey Gowdy, and House Judiciary Committee chairman Bob Goodlatte to see documents related to the Russia investigation.

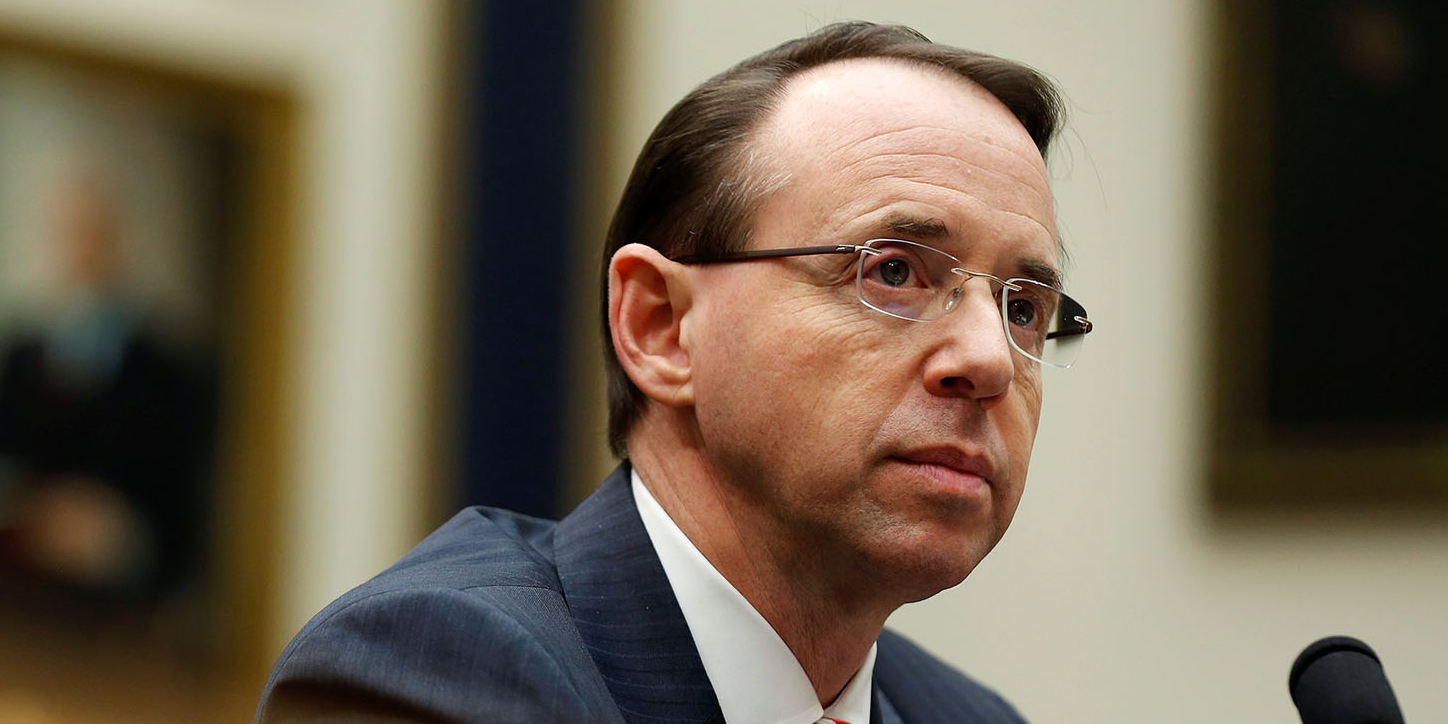

After a tense period in between, during which the three Republican chairmen threatened to hold Deputy Attorney General Rod Rosenstein in contempt of Congress if the DOJ did not turn over the documents, the department sent Comey's memos to Capitol Hill.

The deputy attorney general "is under an incredible amount of pressure," said Harry Litman, a former deputy assistant attorney general. "And normally, rules preventing the release of evidence in ongoing investigations exist precisely to shield department decision-makers from having to bow to this kind of pressure. So it's out of the ordinary and I think unfortunate."

Nunes, the chair of the House Intelligence Committee, is perhaps the most controversial figure in Congress when it comes to the Russia probe. He recused himself from the panel's investigation last year after it surfaced that he secretly traveled to the White House and briefed the administration on classified material without informing his colleagues.

But even after the recusal, Nunes sought to undermine the committee's investigation by conducting his own probe into purported corruption within the DOJ. To that effect, his staff authored a highly controversial memo, released in February, which alleged that the DOJ and FBI abused their surveillance authority when monitoring a former Trump campaign adviser during and after the election.

The DOJ's internal watchdog has since opened an investigation - amid heightened calls from congressional Republicans, the attorney general, and the president - into the FBI's and DOJ's application for a warrant to surveil the former adviser, Carter Page.

Meanwhile, Goodlatte, the chair of the House Judiciary Committee, joined 10 other congressional Republicans this week in sending a letter to the DOJ and FBI asking them to investigate Comey, former Democratic presidential nominee Hillary Clinton, former FBI Deputy Director Andrew McCabe, former Acting Attorney General Sally Yates, and others for purported corruption.

"Giving evidence of an ongoing investigation to Nunes after what we've seen him do is stunning," Cramer said. "But who is really shocked that this was leaked? The DOJ may as well have delivered the memos to the media themselves, it would have saved a step."

Litman agreed: It would be a "disaster" for investigations and those being investigated if "this became more general practice going forward."

But some legal experts aren't so sure that will be the case.

"In a certain sense, this doesn't set any precedent at all because it's so unusual and unique," Cotter said. "I don't see a lot of defense attorneys getting mileage in the future by saying they, too, would like to see FBI reports before a grand jury's even made a move."

'Rosenstein's hands were tied'

Rosenstein, meanwhile, has emerged in recent months as the individual at the center of a tug-of-war between the White House, the DOJ, Congress, and Mueller.

Trump has long simmered over Rosenstein's decision to authorize Mueller to investigate the Trump campaign and the president himself.

But his anger toward Rosenstein reached its apex last week, following news that Rosenstein greenlit the FBI raids of longtime Trump lawyer Michael Cohen's property as part of a federal criminal investigation into him. The White House subsequently began drafting a list of talking points to undermine Rosenstein, and some of Trump's legal advisers reportedly told him they had a strong case to support his firing.

But Trump is said to have backed off from firing Rosenstein after Rosenstein told him Friday that he was not a target in the Cohen probe.

At the same time, Rosenstein and the DOJ were fielding accusations from congressional Republicans of "slow-walking" their response to demands for Comey's memos.

"It's possible Rosenstein's hands were tied, and there's a societal benefit to Rosenstein succumbing to the pressure here, because it helps protect Mueller," Cramer said.

He added: "But if that's the case, you're trying to satiate a beast that can't be satisfied."

Cotter largely agreed.

"Most prosecutors find it appalling whenever any politician violates the separation of powers and rule of law like they did here," he said. "If anything, it probably made it more difficult for Rosenstein to make the decision to turn these memos over."