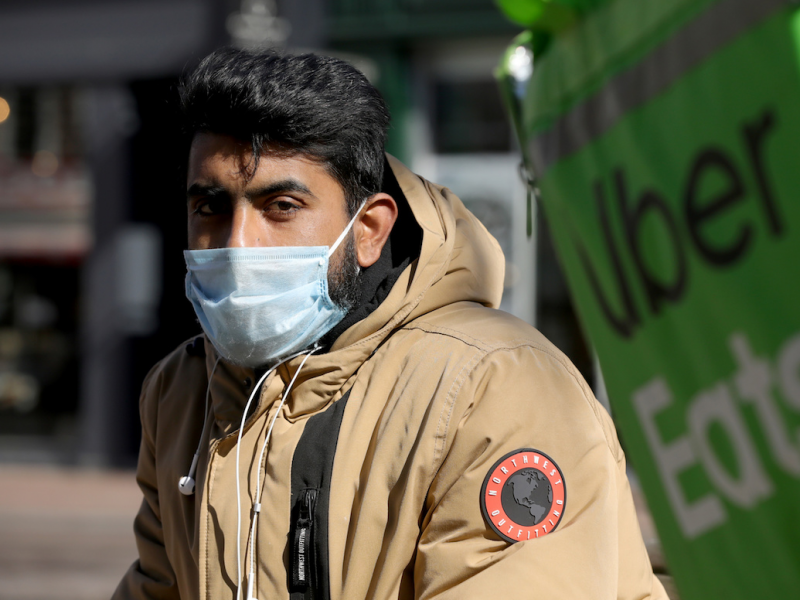

- The White House recommended on Friday that all Americans wear masks, and some US cities like Los Angeles and Laredo, Texas are fining people who don’t cover their faces during the coronavirus pandemic.

- But the public has also been urged to avoid buying medical masks because there is a global shortage, and healthcare workers, who are most exposed to the virus, need them.

- Instead, it’s been suggested that people make their own masks from fabric, or use a bandana or scarf wrapped around the mouth and nose.

- Here’s what we know so far about effectiveness of various types of homemade masks to protect against coronavirus, and why it’s so hard for experts to agree on whether we should wear them.

- Visit Business Insider’s homepage for more stories.

The White House announced on Friday a nationwide recommendation that all Americans wear masks to help slow the spread of the novel coronavirus across the nation.

In Laredo, Texas, officials announced residents could be fined up to $1,000 for not wearing a mask or face covering in public. It’s commonplace in countries like Japan, and in China, it’s considered a civic duty.

But, until now, most Americans have been told to listen to the advice of the World Health Organization and the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, who have repeatedly said that the public should not be buying masks – reluctant to give people a false sense of security from a face-covering that may not filter out all particles, and keen to protect the short supply of surgical masks for medical staff on the front lines who need them most.

Healthcare workers are exposed to a much higher concentration of the virus, both in the form of patients coughing droplets and oxygen machines aerosolizing the virus – for example, when they’re intubating patients – allowing infectious particles to linger in the air. Members of the public are much less likely to encounter particles of the virus in the air, particularly if everyone is avoiding interacting with others and washing their hands as recommended.

However, some experts say that, while masks may not do much to control the spread of the coronavirus, it may be better than no protection at all - particularly on people who think they're healthy but are, in fact, in the early stages of developing a coronavirus illness, unwittingly spreading the virus around when they go grocery shopping.

To protect the public but avoid shortages, officials are increasingly suggesting that people craft their own masks or face coverings out of scarves, bandanas, or t-shirts. And even healthcare workers have been told to use DIY masks "as a last resort."

But it's not clear just how effective those measures are against the novel coronavirus, and there's still a lot we don't understand about the virus, how it spreads, and what kinds of fabrics offer the best protection.

A cloth mask is much less protective than surgical or N95 masks, but it might be 'better than nothing' to stop droplets getting through, research has found

Research on masks' effectiveness against the coronavirus is, at best, inconclusive. Most of what we currently know about masks, from N95s to simple cloth barriers, is based on studies of the flu and other respiratory viruses.

It's unclear if the novel coronavirus is similar in the size of its particles, and the way it moves through the air, to other viruses, or entirely different.

Generally, research suggests surgical masks and N95 respirators are significantly more effective at preventing the spread of viral particles than cloth.

One 2015 study found that cloth masks only blocked 3% of particles, compared with medical masks (which stopped 56% of particles) and N95s (protective against 99.9% of particles, the study found). Healthcare workers wearing cloth masks were significantly more likely to be infected with flu-like illness, the study found. A 2013 study found that cloth masks made from cotton T-shirts, pillowcases, or tea towels should be used only as a last resort - they only filtered out a third of the aerosols blocked by a surgical mask - though it was found to be "better than no protection."

Dr. You-Lo Hsieh, a professor at the University of California, Davis, who studies fiber engineering and polymer chemistry, who was not involved in either of those studies, has also found that viral particles are too small to be caught by most household cloth.

"Common fabrics have pores too large for viruses, that are about 100 nanometer in diameter, and most airborne droplets that contain viruses," Hsieh told Business Insider via email. In contrast, the pore sizes of knitted fabrics are often measured in micrometers, which are 1000 times larger than nanometers. According to the textbook Physico-chemical aspects of Textile Coloration, cotton pores tend to exceed 10-20 micrometers, or 10,000 to 20,000 nanometers.

A 2008 study, however, concluded that while homemade masks may not offer as much protection as surgical masks or N95s, particularly against tiny aerosols, they could still reduce the transmissibility of viral particles by a small but significant amount.

That could be enough to make a difference, said Ben Cowling professor of epidemiology and a mask researcher at the University of Hong Kong's School of Public Health.

"The argument ... about everybody wearing a mask is not that it will prevent everyone from getting infected - it's that it will slow down transmission in the community a bit," Cowling previously told Business Insider. "That's already useful. Just to have even a small effect is useful."

In particular, experts believe masks could be useful, not for people trying to avoid the virus, but for people who already have it, given evidence that people infected with coronavirus can be contagious before they show symptoms. For that purpose, encouraging everyone to wear masks, even inefficient ones, could prevent people unaware that they're infected from spreading the disease in crowded areas such as grocery store lines or public transit, Cowling suggested.

Some DIY materials may be better than others at preventing particles from penetrating through the mask

Some homemade cloth masks may be more effective than others, depending on how tightly-woven the fabric is, and whether it's a good, tight fit.

A 2010 study by the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) tested how well tiny particles could penetrate different materials such as sweatshirts, cotton T-shirts, scarves, and towels.

Sweatshirts were found to offer slightly better protection than tees against the particles - blocking about 20-30% of particles compared to fewer than 14% from the T-shirt. Hanes brand sweatshirts were found to be the most effective in the test, blocking 43-60% of particles. Cotton towels were also found to be more protective than scarves, blocking about 34-40% of particles compared to 11-27% with scarves.

Towels and the Hanes sweatshirt were found to block a slightly higher percentage of particles than commercially available cloth masks.

All of these, though, were significantly less protective than an N95 mask. Researchers weren't able to conclude whether certain materials, such as cotton, polyester, or a blend, were generally more protective. And it's still not clear how any material might fare against the novel coronavirus.

Factors such as how often the materials have been worn or washed could also influence their effectiveness: surgical masks are designed to be single-use - disposed of after they may have come into contact with infectious particles. If a person is reusing their face mask without washing it, that could reduce its effectiveness.

The biggest problem with DIY masks: Unlike surgical masks, household fabrics can absorb viral particles

Textile engineer Emiel DenHartog, Associate Director of the Textile Protection and Comfort Center at North Carolina State University, studies how textiles protect people from chemical and biological threats.

He said "homemade masks may give more peace of mind than actual physical protection" against the novel coronavirus.

One key difference between homemade masks and others is their fabric. Most surgical masks, for example, are manufactured with a non-woven layer of material, which can be key to catching and trapping virus particles.

"Special filtration fabrics - particularly nonwovens - have a distribution of fine fibers in the material that allows only very small openings (pores) so that all particles coming in are intercepted by the fibers in the textile structure," DenHartog told Business Insider via email.

That's quite different from most of our woven and knitted clothing, which is manufactured from porous yarns.

"Even though you might not clearly see these openings in woven and knit fabrics, they are still much larger than many droplets that may contain the virus," DenHartog said.

It's possible, then, that homemade masks might act like virus-catchers, absorbing coronavirus droplets, and getting them perilously close to a wearer's nose and mouth. Taking off a mask can also be hazardous, as you might touch some virus particles on the outside of the mask with your hands or fingers, and then later transfer those to your face.

"There is very limited to no research at all to demonstrate that these effects could be limited in any meaningful way for the general population," DenHartog added. "I prefer to advise people that in personal protection, it is generally not true that anything is better than nothing."

Experts still recommend you stay inside and wash your hands as much as possible because DIY masks may offer a false sense of security

There is no clear consensus from public health officials on masks - in New York, for instance, the state health commissioner reiterated on Friday that there is no good data suggesting people need to wear masks, while New York City Mayor Bill De Blasio has urged people to cover their faces and Gov. Andrew Cuomo suggested that "it won't hurt."

As advice on mask-wearing shifts, experts are keen to emphasize that they should not be seen as a replacement for staying at home, washing your hands, and otherwise practicing social distancing measures.

A main concern, voiced in the 2010 NIOSH study, is that homemade masks could offer a false sense of security.

Hand washing, disinfection, and limiting contact with other people are still regarded as the most effective tactics to prevent the spread of illness. A 2009 meta-analysis found masks could be effective, but only if people wear them consistently and correctly - and they were most protective in combination with proper hand washing.

"[Using respiratory coverings] in itself is not a bad idea, but that doesn't negate the need for hand washing. It doesn't negate the need for physical distancing," Dr. Michael Ryan, executive director of the World Health Organization Health Emergencies Programme, said in a press conference April 3. "It doesn't negate the need for everyone to protect themselves and try to protect others."