- Democrats are poised to pass their inflation bill, but they won't be closing the carried interest loophole.

- Sen. Kyrsten Sinema of Arizona ultimately opposed axing the tax provision, which benefits wealthy investors.

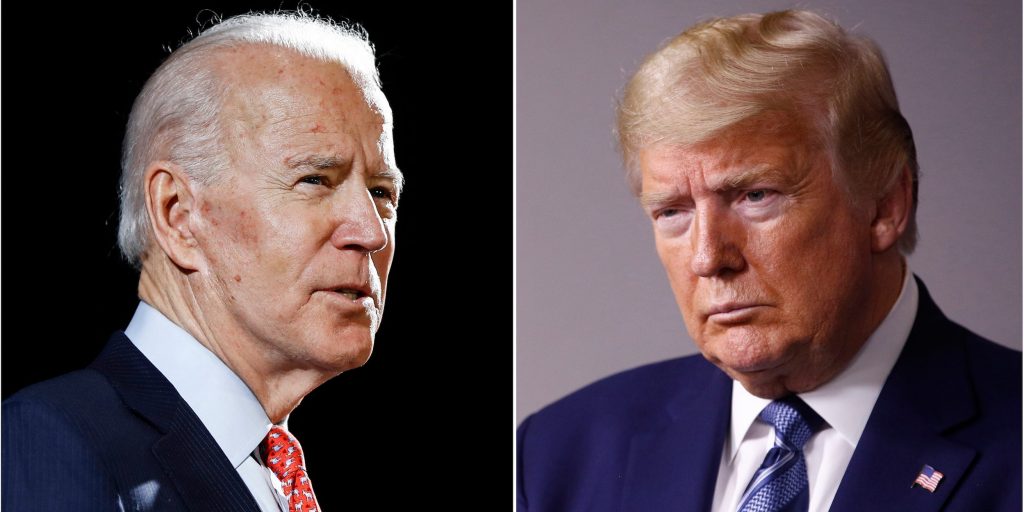

- Calls to close the loophole have come from Presidents Obama, Trump, and Biden.

Both Donald Trump and Barack Obama would've likely supported Democrats' latest attempt to narrow a tax loophole that benefits some of America's wealthiest investors.

But Sen. Kyrsten Sinema of Arizona killed that effort. On this issue, she's an outlier among most Democrats who favored either narrowing it or getting rid of it entirely.

"Senator Sinema said she would not vote for the bill, not even move to proceed unless we took it out," Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer said on Friday. "So, we had no choice."

It's a loss Democrats had to swallow this week in order to get Sinema's vote, as she's been a key centrist holdout in getting Biden's agenda passed in a 50-50 Senate. With that tax provision out of the way, the party reached a deal to pass within days a $740 billion bill investing in climate, healthcare, and the fight against inflation.

While the bill preserves a 1% tax on share buybacks, axing the plan to narrow the carried interest loophole means keeping a tax break largely benefiting wealthy investors that's been a target of former presidents from both parties.

The carried interest loophole allows wealthy investors to treat profits from an asset sale like capital gains instead of income, which means they pay a lower tax rate. It mostly benefits hedge fund managers, real estate investors, and private equity executives, who tend to get their income from cuts of selling investments in real estate or businesses — rather than from a typical paycheck.

Their salaries are structured as assets, rather than a paycheck, and therefore subject to the capital gains tax rate, which is far lower than the income tax most Americans have taken from their paychecks.

Critics have argued that money earned from carried interest is ordinary — rather than investment income — and should be taxed at the 37% income tax rate for the highest earners as a result, rather than the lower capital gains rate of typically 20%. Tax experts previously told Insider that most Americans wouldn't feel the impact of the proposed change.

"For the person at home, it's not going to raise their taxes. It's a loophole closer for very highly paid people who buy and sell companies," Samantha Jacoby, a senior legal tax analyst at the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, said.

That makes it a popular mark across party lines. Barack Obama made repeated efforts during his presidency to close the loophole, but was ultimately unsuccessful. Donald Trump campaigned on closing it as well.

"The hedge fund guys are getting away with murder," Trump said in a 2015 interview. "They're making a tremendous amount of money. They have to pay taxes."

Once in office, an initiative that would have closed the loophole was introduced as part of the Republicans' 2017 tax legislation. But due to significant lobbying from the investment industry, the item was ultimately scrapped and replaced by a more limited narrowing of the tax measure, requiring some investors to hold assets for three years before taking advantage of it.

Predictably, calls to close the loophole resurfaced again when Biden took office. Sinema, however, proved to be the biggest obstacle to Democratic ambitions time and again.

While the Senator has not spoken in depth on the issue, she opposed a similar carried interest initiative during negotiations of the Build Back Better Bill last year. She's also spoken in the past about the "billion of dollars each year" private equity investors provide to small businesses, hinting at a support for the industry. And of course, there's been speculation that campaign contributions she received from investment firms played a role in swaying her as well.

Even with Sinema on board, however, the Inflation Reduction Act would not have closed the loophole entirely, and would have only extended the waiting period from three to five years under its initial proposal — narrowing, not fully closing, the loophole.

In place of the carried interest provision, the Democrats have reportedly added a 1% tax on stock buybacks — when a company buys its own shares to raise the stock price and reward shareholders. While Democrats might have preferred the first draft of the legislation, the buyback tax could raise $125 billion over 10 years, much more than the roughly $14 billion narrowing the loophole was projected to generate over the same timespan.

Critics of stock buybacks have long argued the practice serves to enrich company shareholders and discourages investments in the business and its workers. Given stock buybacks boost share prices, some have argued that discouraging companies from doing so with a tax will ultimately lead to lower share prices — hurting investors big and small.

Others, however, believe companies will continue to dole out the same amount of money to shareholders, but pivot from stock buybacks to more dividends.

"I think the impact here is going to be more about how we cut the shareholder returns pie, rather than does it make any big changes to company investment," Ben Laidler, global markets strategist at eToro, previously told Insider.