- The rise of deepfakes, or videos created using AI that can make it look like someone said or did something they have never done, has raised concerns over how such technology could be used to spread misinformation and damage reputations.

- High-profile figures such as Facebook CEO Mark Zuckerberg, former President Barack Obama, and “Wonder Woman” actress Gal Godot have all appeared in deepfake videos in recent years.

- Congress has been discussing legal measures that could be taken to mitigate the potential damage inflicted by deepfake video content, but doing so without impacting free speech could prove challenging.

- Using algorithms to identify deepfakes could also be difficult considering those who are creating such videos will likely find ways to circumvent such detection methods, experts say.

- Visit Business Insider’s homepage for more stories.

In a video that surfaced about a month ago, Mark Zuckerberg blankly stared into the camera from what appeared to be an office. He made a simple request of his viewers. “Imagine this for a second,” he said. “One man, with total control of billions of people’s stolen data. All their secrets, their lives, their futures.”

Except it wasn’t really the Facebook CEO. It was a digital replica of him known as a deepfake: a phony video created using AI that can make it look like a person said or did something they have never actually done.

Recognizable faces ranging from actor Kit Harrington as Jon Snow from “Game of Thrones” to former President Barack Obama have been the subject of such videos over the past year. And while these videos can be harmless, such as the clip of Jon Snow apologizing for the way the beloved HBO series ended, the technology has raised serious concerns about how manipulating videos and photos through artificial intelligence could potentially be used to spread misinformation or damage one’s reputation.

And according to experts, the deepfake movement isn’t likely to slow down anytime soon.

"Technologically speaking, there is nothing we can do," said Ali Farhadi, senior research manager for the computer vision group at the Allen Institute for Artificial Intelligence. "The technology is out there, [and] people can start using it in whatever way they can."

'We're entering an era in which our enemies can make anyone say anything at any point in time'

It's unclear precisely when deepfakes were invented, but the trend began to gain widespread attention in late 2017 when a fake porn video purporting to feature "Wonder Woman" actress Gal Gadot was published on Reddit by a user who went by the pseudonym "deepfakes," as Vice reported at the time.

Since then, a range of doctored videos featuring high-profile celebrities and politicians have appeared online - some of which are meant to be satirical, others which have portrayed public figures in a negative light, and others which were created to prove a point. Videos of famous movie scenes that had been digitally altered to feature actor Nicholas Cage's face went viral in early 2018, representing the lighter side of the spectrum showing how such tools could be used to foster entertainment.

Then last April, BuzzFeed posted an eerily realistic fake video showing former president Barack Obama saying words he had never spoken as part of an effort to spread awareness about the potential risks that come with using such technology in devious ways. "We're entering an era in which our enemies can make anyone say anything at any point in time," the Obama deepfake says in the video.

Facebook also recently found itself in hot water after it refused to take down a slowed down video of House Speaker Nancy Pelosi that made it look as if she had been intoxicated. While that video wasn't technically a deepfake, it still raised questions about how easily video can be doctored and distributed. At the end of June, a controversial web app called DeepNude allowed users to create realistic naked images of women just by uploading photos to the app, demonstrating how such AI technologies could be used nefariously. The app has since been shut down.

The manipulation of digital video and images is not new. But advancements in artificial intelligence, easier access to tools for altering video, and the scale at which doctored videos can be distributed are. Those latter two points are largely the reason why deepfakes may be prompting more concern than the rise of other photo and video editing tools in the past, says John Villasenor, a nonresident senior fellow at the Brookings Institution and a professor of electrical engineering, public policy, law, and management at the University of California, Los Angeles.

"Everyone's a global broadcaster now," said Villasenor. "So I think it's those two things together that create a fundamentally different landscape than we had when Photoshop came out."

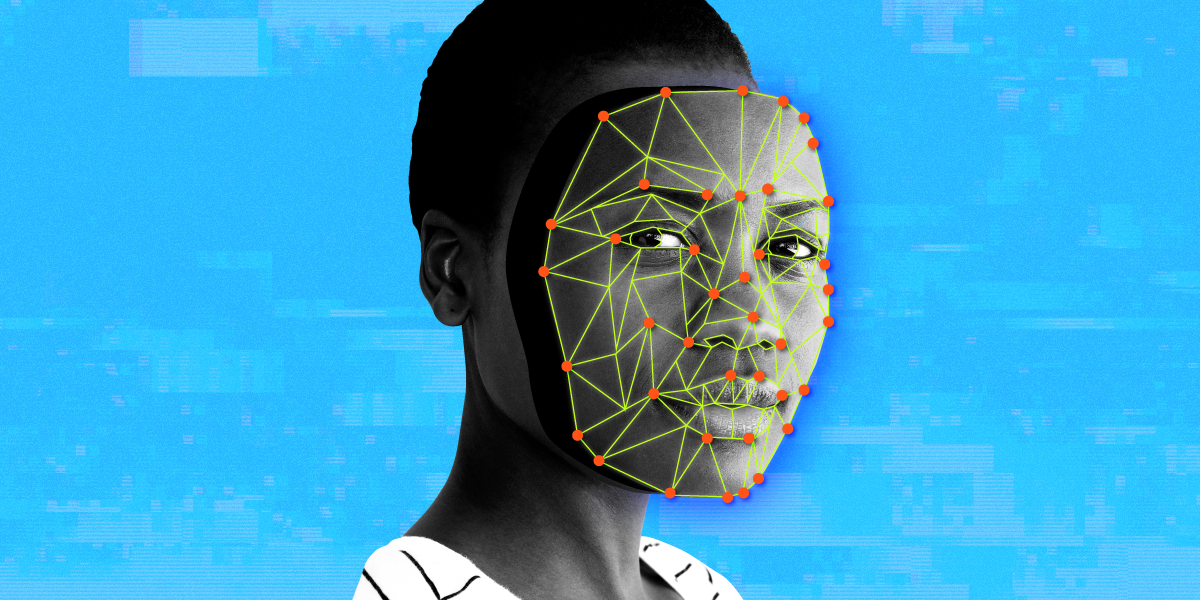

Deepfakes are created by using training data - i.e. images or videos of a subject - to construct a three-dimensional model of a person, according to Villasenor. The amount of data required could vary depending on the system being used and the quality of the deepfake you're trying to create. Developing a convincing deepfake could require thousands of samples, says Farhadi, while Samsung developed an AI system that was able to generate a fabricated video clip with just one photo.

Even though the technology has become more accessible and sophisticated that it once was, it still requires some level of expertise such as an understanding of deep learning algorithms, says Farhadi.

"It's not like with a click of a button you start generating deepfakes," he says. "It's a lot of work."

'An arms race'

It's likely impossible to prevent deepfakes from being created or to prohibit them from spreading on social media and elsewhere. But even if it was possible to do so, outright banning deepfakes likely isn't the solution. That's because it's not the technology itself, but how it's being used, that can be problematic, says Maneesh Agrawala, the Forest Baskett Professor of Computer Science and director of the Brown Institute for Media Innovation at Stanford University. So eliminating deepfakes may not address the root of the issue.

"Misinformation can still be presented even if the video is 100% real," said Agrawala. "So the concern that we have is with misinformation, not so much with the technologies that are creating these videos."

That begs the question as to what can be done to prevent deepfakes from being used in dangerous ways that potentially could cause harm. Experts seem to agree that there are two potential approaches: technological solutions that can detect when a video has been doctored and legal frameworks that penalize those who use the technology to smear others. Neither avenue is fool-proof, and it's still unclear how such fixes would work.

Although a clear solution doesn't exist yet, the question over how to address deepfakes has been a topic of discussion within Congress in recent months. Last December, Republican Senator Ben Sasse of Nebraska proposed a bill known as the "Malicious Deep Fake Prohibition Act of 2018," which seeks to prohibit "fraudulent audiovisual records." The "DEEP FAKES Accountability Act" proposed by New York Democratic Representative Yvette Clarke in June requires that altered media is clearly labeled as such with a watermark. The proposed bill would also impose civil and criminal penalties for violations.

But imposing legislation to crack down on deepfakes in a way that doesn't infringe on free speech or impact public discourse could be challenging, even if such rules do provide exceptions for entertainment content, as the Electronic Frontier Foundation notes.

The Zuckerberg deepfake, for example, was created as part of an exhibit for a documentary festival. "I think it's important to be careful and nuanced in how we talk about the potential for damage," says Agrawala, who along with other researchers from Stanford, Max Planck Institute for Informatics, Princeton University, and Adobe Research created an algorithm that can edit talking-head videos through text. "I think there are a number of really important use cases for that kind of technology."

Plus, taking legal action is often time-consuming, which could make it difficult to use legal measures to mitigate potential harm stemming from deepfakes.

"Election cycles are influenced over the course of sometimes days or even hours with social media, so if someone wants to take legal action that could take weeks or even months," says Villasenor. "And in many cases, the damage may have already been done."

According to Farhadi, one of the most efficient ways to address the issue is to build systems that can distinguish a deepfake from a genuine video. This can be done by using algorithms that are similar to those that have been developed to create deepfakes in the first place, since that data can be used to train the detectors.

But that may not be very helpful for detecting more sophisticated deepfakes as they continue to evolve, says Sean Gourley, the founder and CEO of Primer AI, a machine intelligence firm that builds products for analyzing large data sets.

"You can kind of think of this like zero-day attacks in the cybersecurity space," says Gourley. "The zero-day attack is one that no one's seen before, and thus has no defenses against."

As is often the case with cybersecurity, it can be difficult for those trying to solve issues and patch bugs to remain one step ahead of malicious actors. The same goes for deepfakes, says Villasenor.

"It's sort of an arms race," he says. "You're always going to be a few steps behind on the detection."