- A successful cyberattack on critical infrastructure could do as much damage as a natural disaster, bringing a whole country to a standstill.

- Nations have launched cyberattacks for years. But the world has yet to see a full-power, multipronged attack on a major developed state.

- Experts described in detail to Business Insider how a serious cyberattack could knock flat the systems that underpin all of our lives.

- The US – despite its strengths – is particularly vulnerable because so much infrastructure is controlled by private companies, which may not be well-equipped to deal with a major threat.

Imagine waking up one day and feeling as if a hurricane hit – except everything is still standing.

The lights are out, there is no running water, you have no phone signal, no internet, no heating or air conditioning. Food starts rotting in your fridge, hospitals struggle to save their patients, trains and planes are stuck.

There are none of the collapsed buildings or torn-up trees that accompany a hurricane, and no floodwater. But, all the same, the world you take for granted has collapsed.

This is what it would look like if hackers decided to take your country offline.

Business Insider has researched the state of cyberwarfare, and spoken with experts in cyberdefense, to piece together what a large-scale attack on a country like the US could look like.

Nowadays nations have the ability to cause warlike damage to their enemy's vital infrastructure without launching a military strike, helped along by both new offensive technology and the inexorable drive to connect more and more systems to the internet.

What makes infrastructure systems so vulnerable is that they exist at the crossroads between the digital world and the physical world, said Andrew Tsonchev, the director of technology for the cyberdefense firm Darktrace.

Computers increasingly control operational technologies that were previously in the hands of humans - whether the systems that route electricity through power lines or the mechanism that opens and closes a dam.

"These systems have been connected up to the Wild West of the internet, and there are exponential opportunities to break in to them," Tsonchev said. This creates a vulnerability experts say is especially acute in the US.

Most US critical infrastructure is owned by private businesses, and the state does not incentivize them to prioritize cyberdefense, according to Phil Neray, an industrial cybersecurity expert for the firm CyberX.

"For most of the utilities in the US that monitoring is not in place right now," he said.

One of the most obvious vulnerabilities experts identify is the power grid, relied upon by virtually everyone living and working in a developed country.

Hackers showed that they could plunge thousands of people into darkness when they knocked out parts of the grid in Ukraine in 2015 and 2016. These hits were limited to certain areas, but a more extreme attack could hit a whole network at once.

Researchers for the Pentagon's Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency are preparing for just that kind of scenario.

They told Business Insider just how painstaking - and slow - a restart would be if the US were to lose control of its power lines.

A DARPA program manager, Walter Weiss, has been simulating a blackout on a secretive island the government primarily uses to study infectious animal diseases.

On the highly restricted Plum Island, Weiss and his team ran a worst-case scenario requiring a "black start," in which the grid has to be brought back from deactivation.

"What scares us is that once you lose power it's tough to bring it back online," Weiss said. "Doing that during a cyberattack is even harder because you can't trust the devices you need to restore power for that grid."

The exercise requires experts to fight a barrage of cyberthreats while also grappling with the logistics of restarting the power system in what Weiss called a "degraded environment."

That means coordinating teams across multiple substations without phone or internet access, all while depending on old-fashioned generators that need to be refueled constantly.

Trial runs of this work, Weiss said, showed just how fragile and prone to disruption a recovery effort might be. Substations are often far apart, and minor errors or miscommunications - like forgetting one type of screwdriver - can set an operation back by hours.

A worst-case scenario would require interdependent teams to coordinate these repairs across the entire country, but even an attack on a seemingly less important utility could have a catastrophic impact.

Maritime ports are another prime target - the coastal cities of San Diego and Barcelona, Spain, reported attacks in a single week in 2018.

Both said their core operations stayed intact, but it is easy to imagine how interrupting the complicated logistics and bureaucracy of a modern shipping hub could ravage global trade, 90% of which is ocean-borne.

Itai Sela, the CEO of the cybersecurity firm Naval Dome, told a recent conference that "the shipping industry should be on red alert" because of the cyberthreat.

The world has already seen glimpses of the destruction a multipronged cyberattack could cause.

In 2010, the Israeli-American Stuxnet virus targeted the Iranian nuclear program, reportedly ruining one-fifth of its enrichment facilities. It taught the world's militaries that cyberattacks were a real threat.

Read more: The Stuxnet attack on Iran's nuclear plant was 'far more dangerous' than previously thought

The most intense frontier of cyberwarfare is Ukraine, which is fighting a simmering conflict against Russia.

Besides the attacks on the power grid, the devastating NotPetya malware in 2017 paralyzed Ukrainian utility companies, banks, and government agencies. The malware proved so virulent that it spread to other countries.

Hackers have also caused significant disruption with so-called ransomware, which freezes computer systems unless the users had over large sums of money, often in hard-to-trace cryptocurrency.

An attack on local government services in Baltimore has frozen about 10,000 computers since May 7, getting in the way of ordinary activities like selling homes and paying the water bill. Again, this is proof of concept for something far larger.

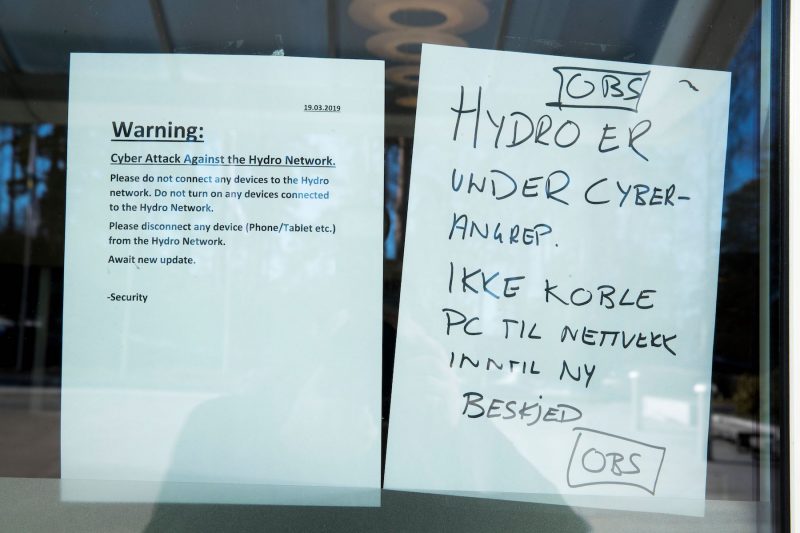

In March this year, a cyberattack on one of the world's largest aluminum producers, the Oslo-based Norsk Hydro, forced it to close several plants that provide parts for carmakers and builders.

In 2017 the WannaCry virus, designed to infect computers to extract a ransom, burst onto the internet and caused damage beyond anything its creators could have foreseen.

It forced Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co., the world's biggest contract chipmaker, to shut down production for three days. In the UK, 200,000 computers used by the National Health System were compromised, halting medical treatment and costing nearly $120 million.

The US government said North Korean hackers were behind the ransomware.

Read more: Trump administration goes on media blitz to blame North Korea for massive WannaCry cyber attack

North Korean hackers were also blamed for the 2015 attack that leaked personal information from thousands of Sony employees to prevent the release of "The Dictator," a fictional comedy about Kim Jong Un.

These isolated events were middling to major news events when they happened. But they occur against a backdrop of lesser activity that rarely makes the news.

The reason we don't hear about more attacks like this isn't because nobody is trying - governments regularly tell us they are fending off constant attacks from adversaries.

In the US, the FBI and the Department of Homeland Security say Russian government hackers have managed to infiltrate critical infrastructure like the energy, nuclear, and manufacturing sectors.

The UK's National Security Centre says it repels about 10 attempted cyberattacks from hostile states every week.

Though the capacity is there, as with most large-scale acts of war, state actors are fearful to pull the trigger.

James Andrew Lewis, a senior vice president and technology director at the Center for Strategic and International Studies, told Business Insider the fear of retaliation kept many hackers in check.

"The caveat is how a country like the US would retaliate," he said. "An attack on this scale would be a major geopolitical move."

Despite the growing dangers, this uneasy and unspoken truce has kept the threat far from most people's minds. For that to change, Lewis believes, it would require a large-scale attack with tangible consequences.

"I'm often asked: How many people have died in a cyberattack? Zero," he said.

"Maybe that's the threshold. People underappreciate the effects that aren't immediately visible to them."