- Deadly violence rose again in Costa Rica in 2017, continuing a sustained increase seen over the past few years.

- While Costa Rica’s security situation is far better than its neighbors, homicides are at levels the country has never seen before.

- Drugs and drug trafficking have been blamed for the increased violence, and it’s not clear the government can mount an effective response.

Homicides in Costa Rica hit a record level in 2017, as 603 people were killed – 25 more than the 578 homicides in 2016, a record at the time.

This continues a climb seen since 2012, when there were 407 killings.

Costa Rica, home to about 5 million people, closed 2017 with a homicide rate of 12.1 per 100,000 people. While that is just a fraction of the homicide rates in Central America’s Northern Triangle – Guatemala, 26.1 homicides per 100,000 people; Honduras, 42.8 per 100,000; and El Salvador, 60 per 100,000 – it is the highest that Costa Rica has ever seen and more than double the rate registered in the US.

Central America is among the most violent regions in the world, and much of the violence is related to gangs and drug-related crime. While the security situation in Costa Rica is much different than other countries in the region, many of the killings there during the past year were attributed to drugs and drug trafficking.

Michael Soto, the deputy director of Costa Rica's judicial investigation body, said 48% of the deaths stemmed from gang violence, while 25% were related to drug trafficking. Fights and other causes, like domestic violence, led to the rest. Seventy-two percent of the homicides were committed with firearms, the most common cause.

"Poor neighborhoods have problems with crime and violence but not [a] significant organized gang presence," Geoff Thale, program director at the Washington Office on Latin America, told Business Insider. "So I think in the Costa Rica context, it mostly is drug trafficking and the effects of fights over trafficking routes and control of trafficking routes."

Most illegal drugs smuggled into the US travel through Mexico after making their way through Central America. Costa Rica and its neighbors have long been transshipment points for drugs heading north, and the increase in homicides appears to be centered in areas where drug activity has increased - namely, urban areas and areas along the coasts.

Nearly three-quarters of Costa Rica's homicides in 2017 were concentrated in three of the country's seven provinces.

Four hundred and twenty five homicides, or 71% of the total, took place in San Jose, which includes the capital city of the same name; Limon, which covers the entire Caribbean coast; and Alajuela, which abuts the northern border.

Other countries have seen more intense transshipment activity, but Coast Rica has seen a big increase in such movement, Thale told Business Insider.

"Along the Atlantic coast, stuff comes in ... and along the route, along the coastline in particular, there's trafficking organizations operating," Thale said.

"And there's lots local conflict over who controls the route or who pays who off and stuff," he added. "Even though most of that is a flow north, there's a spillover effect in the cities, San Jose in particular."

Costa Rican security officials have said they are not able to stop drug traffickers from making use of their territory.

"There does not exist a beach in Costa Rica where narcos haven't penetrated with a boat with cocaine, coming from Colombia," Public Security Minister Gustavo Mata told legislators in February 2017.

Mata also pointed to an increase in marijuana trafficked by Jamaican groups, who, he said, worked with Costa Ricans in Limon province. "That situation caused much of the homicides that there were" in 2016, he said.

Mata said in December that the country hadn't taken measures to confront the wave of drugs being trafficked through Costa Rica and that the country was seeing full-fledged "narcotrafficking," rather than "narcomenudeo" and "microtrafico" - terms for small-scale or street-level drug sales.

Costa Rican coast-guard officials said in mid-2017 that the number of suspected drug-trafficking boats detected in the country's waters doubled between 2013 and 2016, with the majority spotted in near southern Pacific coast. One coast guard official compared the activity to "a plague."

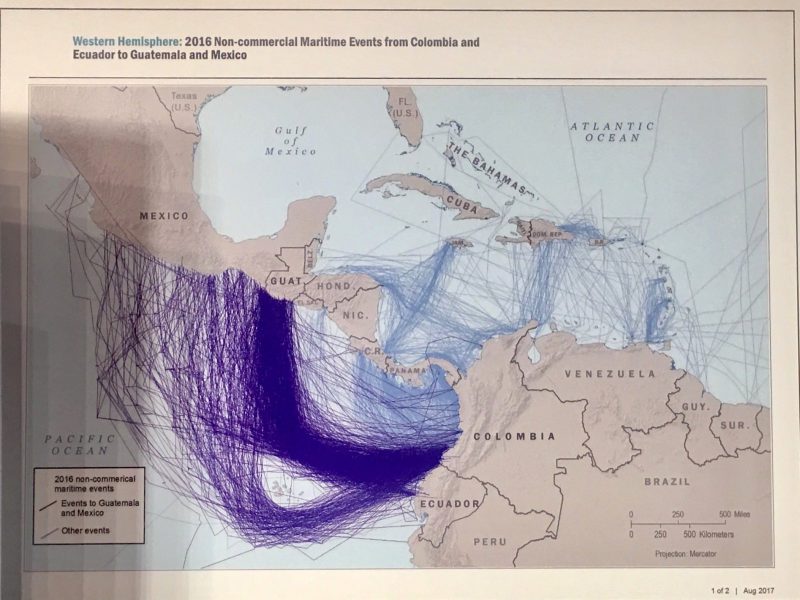

"A lot of that stuff you see going into Costa Rica, that's when they first track it, and then it'll take these short hops up the coast, whichever coast it's on," Adam Isacson, WOLA's senior associate for defense oversight, told Business Insider in late 2017, describing trafficking routes detected by US authorities in 2016.

"Just like a little ant going up and up the coast in little hops and then probably getting into Mexico, where it'll start going overland," Isacson said.

Some of the drugs being trafficked through Costa Rica travel overland routes, said Mike Allison, a University of Scranton political-science professor who has done research in the region.

That movement "leads to corruption and the buying off of police and border-patrol agents and perhaps to threats of the killing of those who ... won't accept bribes," he told Business Insider.

'It's likely this curve will keep going up'

Authorities in Costa Rica have warned for some time that the country's violence was directly linked to drugs.

Seventy percent of the 570 homicides in 2015 were reportedly the result of fighting between drug groups. In late 2016, Costa Rican authorities dismantled a drug-trafficking network linked to the Sinaloa cartel. The Zetas and Gulf cartels are also reportedly present in the region.

The country's attorney general - who previously warned that Mexican cartels were arming Costa Rican gangs - said last year that Mexican cartels were recruiting local criminals, training them in Mexico, and returning them to Costa Rica to apply cartel tactics.

"We have an increase in violence because local drug trafficking organizations are applying the Mexican strategy of controlling territory," the attorney general, Jorge Chavarria, said in February 2017.

The "Mexican recipe," as Chavarria described it last summer, led to local gangs - driven by a greater supply of drugs - to focus on supplying local consumption, which in turn led to violent attempts to monopolize the local market.

"I imagine we're seeing ... that people are being paid in drugs," Allison said, "and so [you] see an increase in ... drug availability and use in Costa Rica and elsewhere, as ... they pay off the people simply by providing them drugs."

Walter Espinoza, the chief of the judicial investigation body, said in late December that killings of criminal leaders could led to further violence, as those groups fight over leadership and control of territory - a phenomenon seen in Mexico as a result of the Kingpin anti-crime strategy.

"In recent years we do not remember a situation like that which we are experiencing," Espinoza told the press in December. There have been recent reports of communities near San Jose being controlled by criminal groups, who extort businesses operating there.

Costa Rica has reduced police training in order to deploy more officers (less training may make those officers more susceptible to bribery) and partnered with neighbors to combat organized crime. Costa Rica's police also flew more than 3,400 hours of surveillance flights over the country's coasts, mountains, and communities, in 2017, and next year the country's coast guard will acquire two 110-foot patrol ships donated by the US.

The latest evidence of a sustained increase in violence in Costa Rica comes as the country prepares for February 4 elections that will select the president, first and second vice president, and 57 members of the legislature.

The timing has reinvigorated debate about how to approach insecurity, whether through "mano dura" policies popular elsewhere in the region or with other, more comprehensive policies that address violence as a result of social conditions, like increasing inequality over the last two decades.

Surveys in the final months of 2017 put security as the fourth most pressing concern among Costa Ricans, behind unemployment, corruption, and the economy - but ahead of poverty. Seven presidential candidates held a debate in a prison in November, focusing on issues in criminal justice and crime-fighting. ("I hope you feel at home," one prisoner told the candidates.)

However security concerns factor into the voting in February, and into the potential runoff in April, crime and violence look set to remain problems in Costa Rica.

"Since 2012, we have seen an increase, and it's likely this curve will keep going up unless something extraordinary happens," Soto, of the judicial investigation body, said earlier this month. But, he stressed, "we are not losing control, and we are at the same level as in other societies."