- The first case of the novel coronavirus emerged on November 17, according to Chinese government data reviewed by South China Morning Post.

- The identity of the person has not been confirmed, but it appears to be a 55-year-old from the Hubei province, the Post said.

- It wasn’t until December that Chinese authorities realized they had a new type of virus on their hands.

- Visit Business Insider’s homepage for more stories.

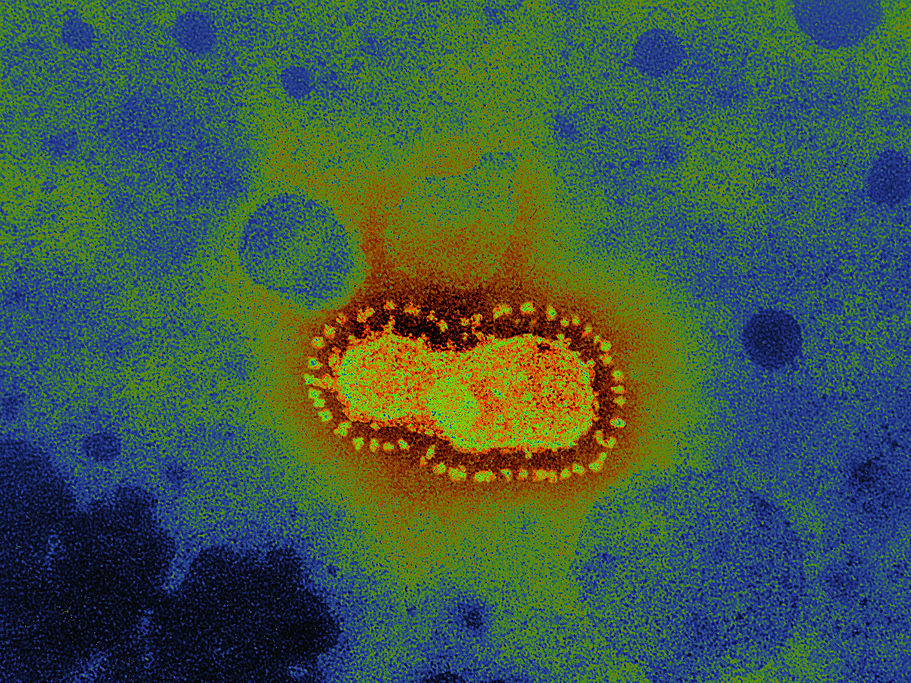

The first case of the novel coronavirus emerged on November 17, according to Chinese government data reviewed by the South China Morning Post.

It wasn’t until late December that Chinese officials realized they had a new virus on their hands. But even then, China’s government clamped down on sharing information about it with the public, according to The Wall Street Journal.

The Post said the data it reviewed, which has not been made public, suggested that the virus was first contracted by a 55-year-old man from China’s Hubei province.

But as the newspaper noted, the evidence is not conclusive. The identity of “patient zero” – the first human case of the virus – has still not been confirmed, and it’s possible that the data set isn’t complete.

New data about 'patient zero' is consistent with other research

Chinese health authorities reported the first case of COVID-19, the illness caused by the coronavirus, to the World Health Organization on December 31.

A team of researchers later published evidence that the first person to test positive was showing symptoms on December 8, the date of the first confirmed case.

Other research published in The Lancet in January found that the first person to test positive was exposed to the virus on December 1.

The fact that researchers have continually hiked back the likely date of the earliest infection means there still may not be enough evidence to identify "patient zero," but the new Chinese government data reported by the Post sharpens what we know.

Research published last month by a team of infectious-disease researchers from China found that WeChat users were using terms related to symptoms of the novel coronavirus more than two weeks before officials confirmed the first case.

"The findings might indicate that the coronavirus started circulating weeks before the first cases were officially diagnosed and reported," Business Insider's Holly Secon wrote.

The research lends further support to the finding that the earliest case of the novel coronavirus did indeed originate in mid-November.

Identifying patient zero is important for containing the virus

As officials try to identify patient zero, the new government data reported by the Post provides clues about the emergence and spread of a virus that has thrown the world into tumult.

"We don't know who the very first patient zero was, presumably in Wuhan, and that leaves a lot of unanswered questions about how the outbreak started and how it initially spread," Sarah Borwein, a doctor at Hong Kong's Central Health Medical Practice, told the Post last month.

For experts, finding patient zero is not simply a matter of digging through data and conducting research - it's a race against the clock.

As the number of infections increases, it becomes more difficult to identify that person - and the areas that have been exposed to the virus the longest.

"We do feel uncomfortable obviously when we diagnose a patient with the illness and we can't work out where it came from," Dale Fisher, the chair of the WHO's Global Outbreak Alert and Response Network, told Reuters last month, adding that "the containment activities are less effective."

- Read more:

- Taiwan has only 50 coronavirus cases. Its response to the crisis shows that swift action and widespread healthcare can prevent an outbreak.

- The US is severely under-testing for coronavirus as death toll and new cases rise

- Chinese social-media platform WeChat saw spikes in the terms 'SARS,' 'coronavirus,' and 'shortness of breath,' weeks before the first cases were confirmed, a study suggests

- Travel bans in Wuhan only delayed the coronavirus' spread in China by 3 to 5 days, and in the rest of the world by a few weeks, new research shows