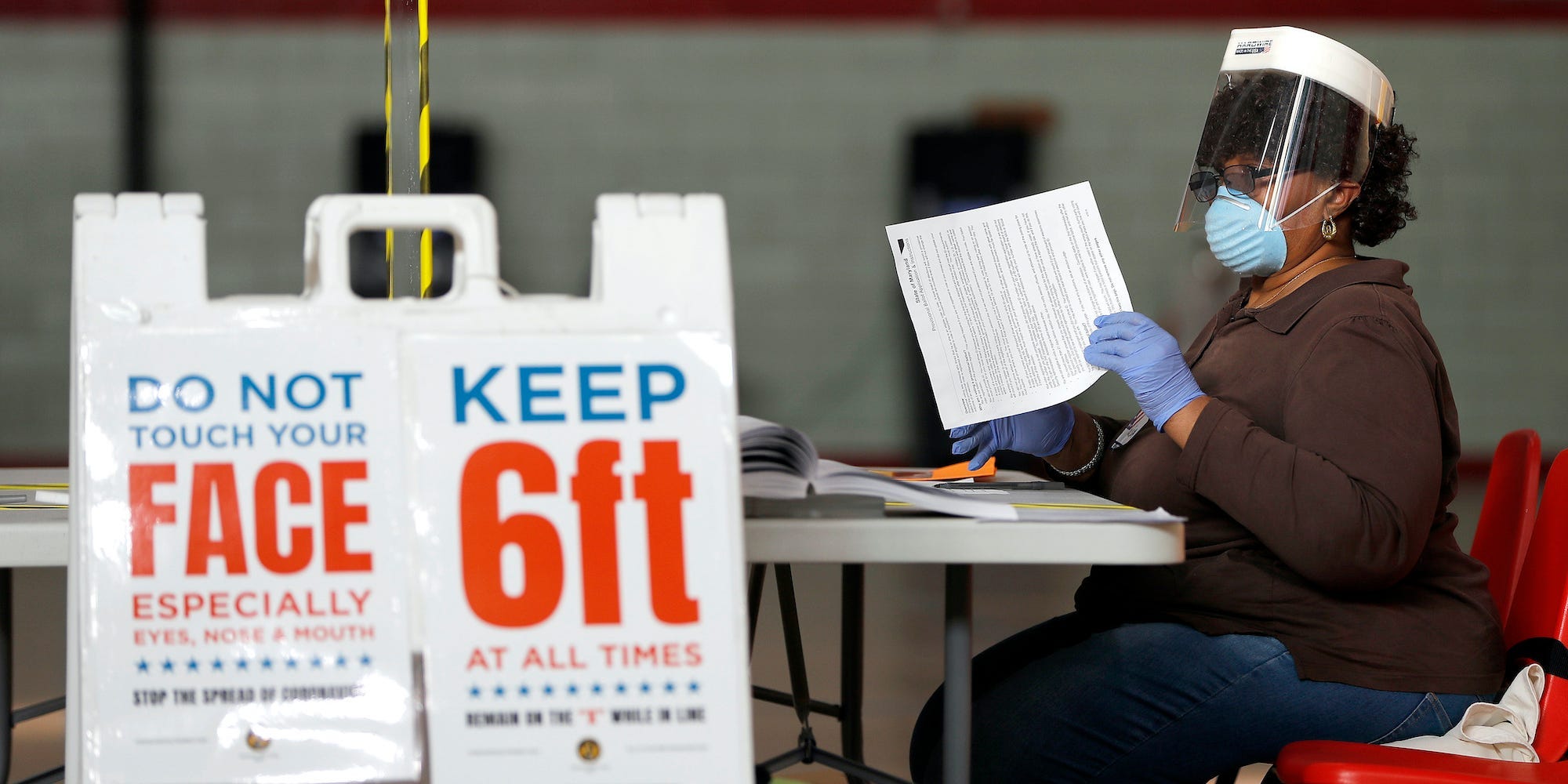

Andrew Harnik/AP

- Congress likely won't weigh in on the growing threat of election subversion in the states.

- States are passing laws criminalizing and politicizing the election and vote-counting process.

- Experts suggest standardizing vote-counting procedures and reforming the Electoral Count Act.

- See more stories on Insider's business page.

Congress will almost certainly sit out the ongoing high-stakes fight within states over how people vote, and who has power over how elections are run.

The Senate is gearing up for a showdown over voting rights and the filibuster at the end of June, amid the backdrop Republican state legislators passing an unprecedented number of laws tightening rules for voters and election officials.

Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer is bringing the For The People Act (known as HR. 1 in the House and S. 1 in the Senate), Democrats' 800-plus page flagship voting rights and democracy reform bill, up for a floor vote the week of June 21.

The chances of Congress passing that legislation went from extraordinarily slim to none after moderate Democratic Sen. Joe Manchin formally came out against the bill in a June 6 op-ed in the Charleston Gazette-Mail.

Within the current Senate filibuster rules (which Manchin also supports), the bill, which has no GOP support, would need Manchin and at least 10 Republican votes to pass the US Senate.

Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell also threw cold water on H.R. 4, Manchin and Sen. Lisa Murkowski's proposed bipartisan alternative to the For The People Act that would restore a key provision of the Voting Rights Act struck down by the Supreme Court in 2013.

Democratic politicians and civil rights advocates have largely criticized the bills and Manchin's refusal to sign on to S.1 by framing them in the language of voter suppression instead of electoral subversion.

Much of their messaging has zeroed in on the implications for the voting process, like new provisions in GOP-backed state laws that add new ID requirements, tighten the rules to vote by mail, and limit who can give out food and water to voters in line.

By loosening voter ID rules and expanding early and mail voting, S. 1 would invalidate many of the provisions in new GOP-backed laws that place stricter rules on voters.

But, as numerous scholars and analysts have pointed out, those changes to the voting process have overshadowed the more insidious trend of lawmakers seizing control over the voting and vote-counting process away from local election officials.

AP Photo/Julio Cortez, file

Election subversion is an emerging threat.

A June update to a report from Protect Democracy, States United Democracy Center, and Law Forward identified 216 GOP-backed proposed state laws in 41 states that criminalize aspects of the election administration process and give partisan officials more control over how elections are conducted and certified.

As of early June, 24 of those laws have been signed into law and enacted in 14 GOP-controlled states.

That's in addition to controversial GOP-backed efforts with highly dubious methodology to review already-audited election results in places like Maricopa County, Arizona that could be replicated in other states.

The provisions in the new state laws would impose new civil and criminal penalties on election officials, strip executive authority over elections from governors and secretaries of state, and give partisan state legislatures more power to meddle in election administration - and, in some cases, determine or even overturn election results.

Neither S.1 or H.R. 4 address those more dangerous provisions that politicize the work of US election workers and set them up to face potential criminal charges. In Texas' bill, for example, it would be a felony for an election official send an absentee ballot application to a voter who didn't request one.

While the For the People Act does include measures to protect the integrity of election results, like requiring states to use voter-verifiable paper ballots and allocating federal grant money for voting technology upgrades and risk-limiting audits, neither that bill nor H.R. 4 set standards to protect election officials and election results from partisan manipulation.

"We have to remember that HR. 1 was almost entirely written in 2018 and 2019 pre-COVID, pre-2020 election," David Becker, executive director of the nonpartisan Center for Election Innovation and Research, told Insider. "It addresses perceived problems with the system that existed back then, and we've all been through a lot since then. It was changed virtually not at all before introduction in this Congress again."

The New York Times editorial board, which had previously endorsed S. 1, called it "poorly matched to the moment" in a June 4 editorial, arguing that "the legislation attempts to accomplish more than is currently feasible, while failing to address some of the clearest threats to democracy, especially the prospect that state officials will seek to overturn the will of voters."

AP Photo/Eric Gay, file

Congress could make vote-counting more "ministerial."

Georgia's omnibus election bill SB 202, which Gov. Brian Kemp signed into law in late March, demotes Secretary of State Brad Raffensperger from the chair of the State Elections Board to a non-voting member, gives the Board more authority to discipline and temporarily remove local election officials, and bans local officials from accepting private grants to help run their elections.

Texas' Senate Bill 7, which state House Democrats temporarily prevented from being passed in a dramatic Memorial Day weekend walkout, includes 14 new criminal penalties for election officials and a controversial provision that would make it easier to overturn some elections, which legislative leaders are now walking back ahead of a likely special session.

In Arizona, a proposed budget bill would strip Democratic Secretary of State Katie Hobbs of the authority to represent the state in election lawsuits and give that power to Republican Attorney General Mark Brnovich - but only until 2023. (Both are 2022 candidates for governor and US Senate, respectively).

But what could Congress do?

Congress has jurisdiction to regulate the "time, place, and manner" of federal elections under the Elections Clause of the Constitution. Existing federal laws mainly set far more federal regulations over the voting and election administration process than the post-election vote-counting and certification process.

Becker argued that one congressional reform to protect against election subversion for federal elections could be depoliticizing and standardizing the certification process to take the fate of election results out of the hands of individual public officials who could be subject to partisan interference and pressure.

"I think it's fair to say that it would be a much better situation, at least with regard to federal elections, to render the act of counting the ballots and certifying the ballots as a more ministerial act. I think that would be a favor to election officials. No election official in the country wants to be in the position Secretary Raffensperger in Georgia found himself in," he said, referring to the infamous January phone call where Trump begged Raffensperger to "find" 11,780 votes after Georgia's presidential election results had already been audited and recounted twice.

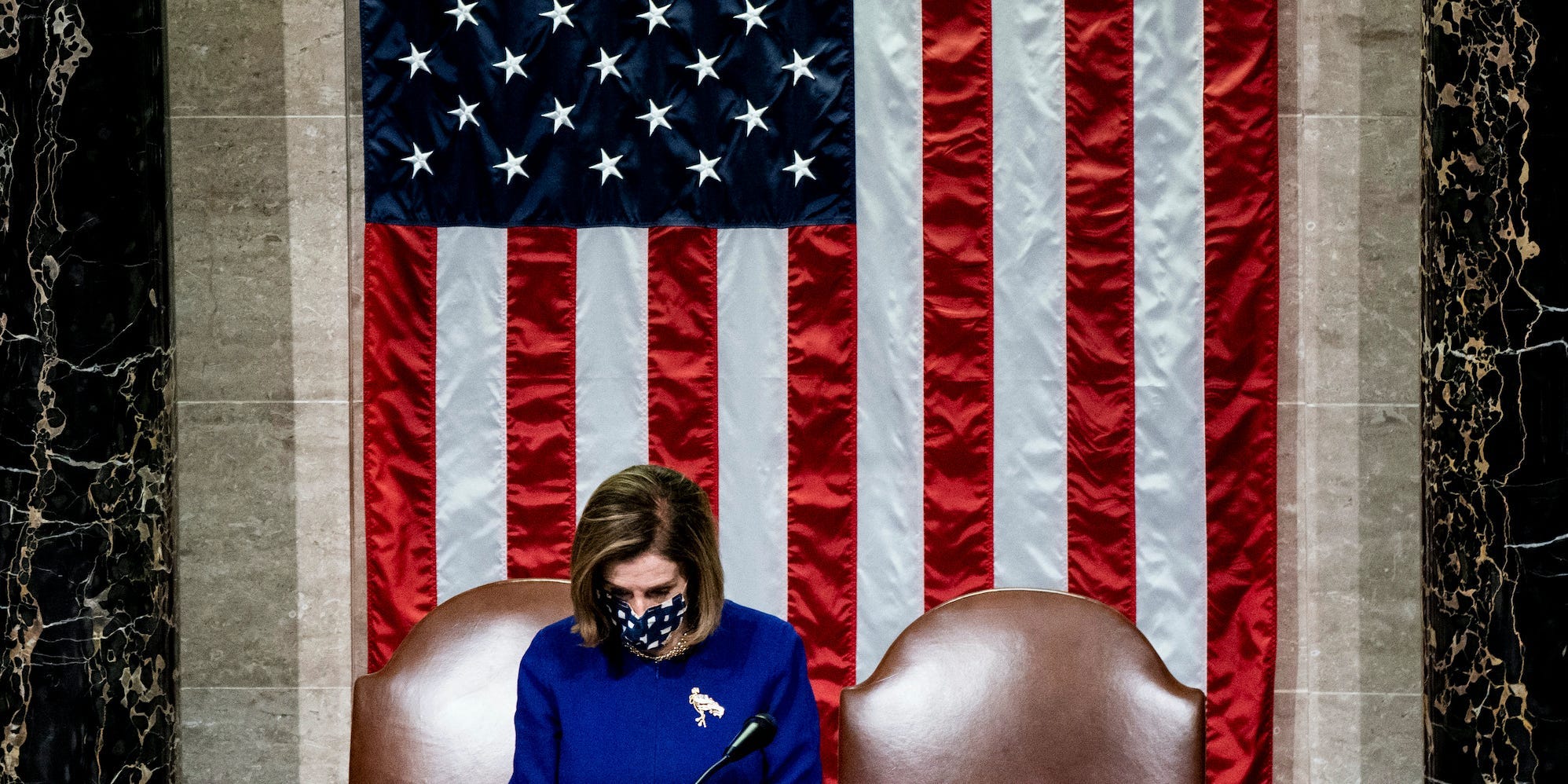

Erin Schaff/The New York Times via AP, Pool

Modernizing how Congress counts electoral votes is another area potentially ripe for reform.

Becker and other legal experts have long called for reforms to the Electoral Count of Act of 1887, which established processes for Congress to count electoral votes and resolve disputed elections.

The law took center stage on January 6, 2021, when dozens of GOP lawmakers objected to fully certified slates of electors from Arizona and Pennsylvania as rioters breached the Capitol in an insurrection to try and stop the vote counting.

"I think the Electoral Count Act, for an act written in the 1880s, actually held up remarkably well given the world we currently live in. But, it also clearly wasn't intended to be a way for members of Congress who simply didn't like the results to hold up the legitimate election of a president," Becker said.

It allows one member of the House and one member of the Senate to raise objections to slates of electors that they claim aren't "lawfully certified" or "regularly given," a relatively vague standard.

"The first problem is that that [the law] is very unclear and convoluted. And the stakes of a disputed presidential election are so high that clarity and certainty in the law are critically important, and we saw some of the price of the lack of clarity this year," Matthew Seligman, special counsel at the Campaign Legal Center, said at a recent American Enterprise Institute panel on the future of the law.

Seligman and the other scholars suggested that Congress could update the act's language to raise the threshold for bringing an objection, narrow the grounds for objections to specific scenarios clearly laid out in the law, emphasize that Congress should defer to the outcome of state-level recounts and court challenges, and clarify the vice president's role.

"The problem with the statute as it's written is that there's supposed to be this deference towards the resolution of election disputes as courts and states have resolved them, but there's no enforcement mechanism, and we saw that supposed presumption tossed out the window this year," Siegelman said.

While the chances of Congress overturning the results of a future presidential election are probably slim, the lack of clarity and relatively low bar to objecting election results leaves the law more open to partisan manipulation and abuse.

"Conservatives should be particularly motivated to find a way to improve the ECA. Why? Because a Democrat, Vice President Kamala Harris, will be presiding over the electoral count in 2025," AEI resident scholar Kevin Kosar and panel moderator said at the panel on the future of the law.