- Congress is back at square one on voting rights and election reform.

- A bipartisan group of senators is discussing reforms to the Electoral Count Act of 1887.

- The discussions are still a ways off from being finalized and it's unclear if congressional leadership will be on board.

Congressional Democrats are trudging back to the drawing board to revive both President Joe Biden's stalled social spending package and the party's election reform push.

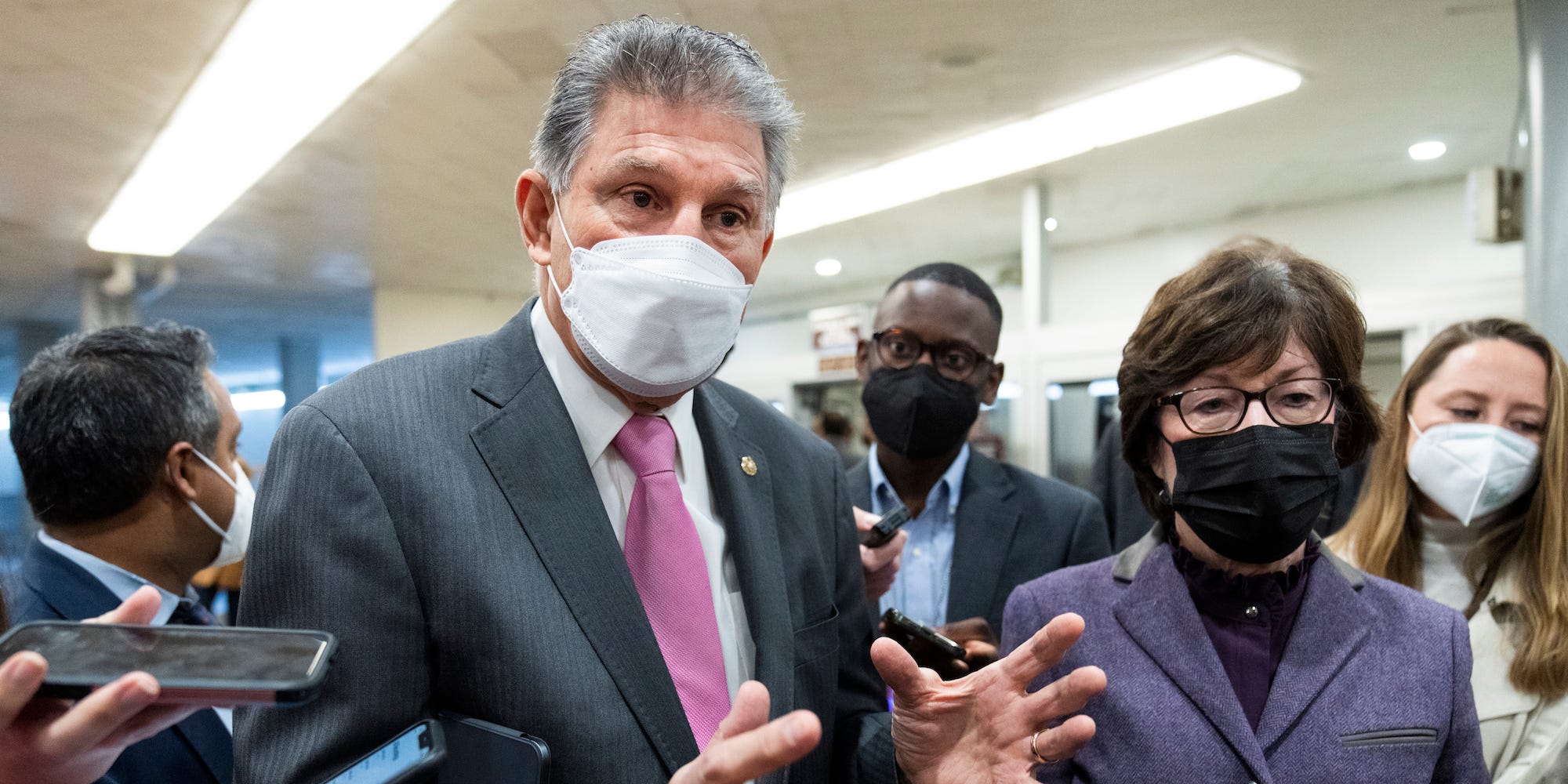

Late Wednesday night, all 50 Senate Republicans blocked a debate on The Freedom to Vote: John R. Lewis Act, a sweeping Democratic voting rights bill. Shortly after, they were joined by two of their Democratic colleagues — Sens. Joe Manchin and Kyrsten Sinema — in voting down changes to the Senate filibuster, the bill's final nail in the coffin.

If nothing else, Wednesday night's failed votes definitively proved that all voting rights and election reform legislation will need 60 votes to pass in the Senate.

What happens next?

Progressive lawmakers and the Congressional Black Caucus remain committed to getting back to work on passing comprehensive voting rights protections.

But the likeliest outcome, given the current split in the Senate, is a bipartisan compromise hashed out by members of the upper chamber.

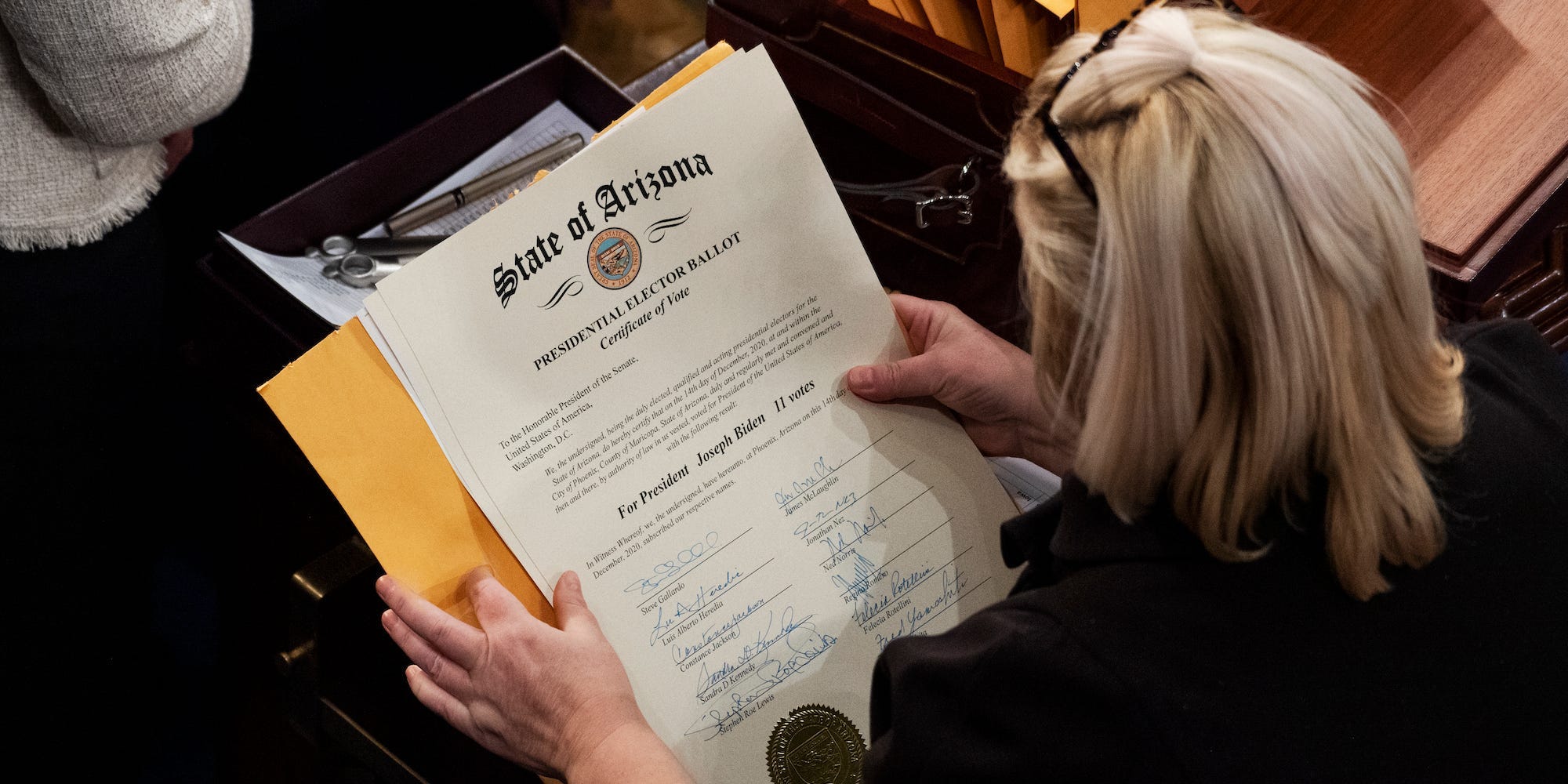

Any bipartisan election bill would likely center around reforms to the Electoral Count Act of 1887 — or ECA – which sets the parameters for how Congress counts presidential electors and resolves disputes over presidential election results in the Electoral College.

Sens. Amy Klobuchar and Angus King are set to spearhead an ECA reform bill. And a growing bipartisan group of lawmakers, which is led by Manchin and GOP Sen. Susan Collins, is also working on the issue separately. Senators in this group are also considering the inclusion of more funding for elections and federal protections against harassment and intimidation of election workers in what would potentially be a bipartisan package.

What is the Electoral Count Act and why do some Congress members want to fix it?

The ECA came out of the contested presidential election of 1876 between Democrat Samuel Tilden and Republican Rutherford B. Hayes, which dissolved into a full-on crisis when several states sent multiple slates of presidential electors to Congress. A 15-member commission was tasked with deciding the true winner of the election, and the impasse only ended by Democrats agreeing to accept Hayes as president in exchange for him ending reconstruction in the South. This was a period when the US was addressing slavery and fallout from the Civil War, and Hayes' move led to the Jim Crow era of racial segregation and oppression.

Congress' eventual solution to prevent a similarly acrimonious election crisis was far from perfect.

"With another potentially close election fast approaching, Congress wanted additional procedures in place. They knew that the compromise they cobbled together in the act was flawed," election scholars Ned Foley and Larry Diamond wrote in The Atlantic in 2020. "A leading political scientist of the day called it 'almost unintelligible.' We defy anyone to read its operative section, a morass of contorted syntax, and profess to truly understand its meaning with respect to the circumstance when it would matter most."

For a law written in the 1880s, the ECA has fared pretty well over the years, but that changed in the lead-up to January 6, 2021.

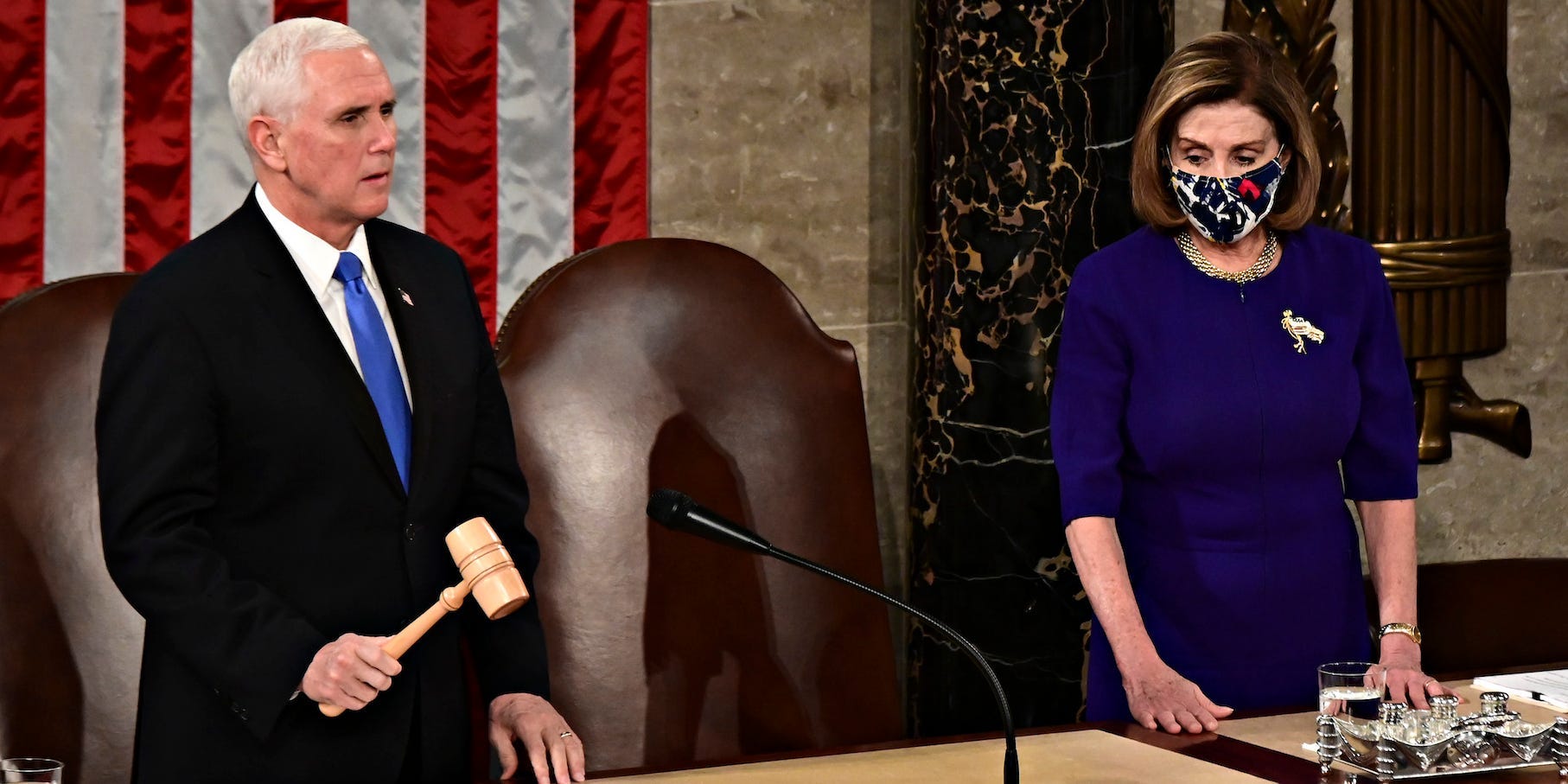

The once-obscure law took center stage when former President Donald Trump and his allies unsuccessfully lobbied Republican state legislatures to send in alternative slates of presidential electors and pressured former Vice President Mike Pence to use his ceremonial role overseeing the proceedings that day to delay and even subvert the ratification of President Joe Biden's Electoral College victory.

"I wish that this wasn't an issue," Matthew Seligman, an ECA scholar and fellow at Yale Law School, told Insider. "I started thinking about this in 2016, and I was thinking about it as a potentially hypothetical problem, but I was genuinely worried about it. But nobody else, or very few other people, were really thinking about this type of election manipulation."

The law's confusing and unclear phrasing on key issues creates ambiguity that leaves a door open for overt partisan manipulation of presidential election results at both the state and federal levels.

Legal scholars and experts from across the political spectrum have long advocated for giving the law a 21st century-refresh and fortifying it against some of the modern-day partisan meddling seen in 2021.

That could include establishing the vice president's role as solely ministerial, raising the threshold for bringing an objection, clarifying the grounds for objections, emphasizing that Congress should generally defer to state-level outcomes, and fixing provisions of the act that currently enable subversion of election results at the state level.

What's working for against bipartisan election reform?

Several members of the bipartisan group now working on election reform have a recent track record of success in the Senate. They negotiated a landmark $1.2 trillion bipartisan infrastructure bill, which passed both chambers of Congress in 2021.

A number of top GOP lawmakers in both chambers, including Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell, Minority Whip John Thune, House Minority Leader Kevin McCarthy, and Republican Study Committee Chair Rep. Jim Banks, are interested and open to the idea of ECA reform.

Democrats are also likely feeling an increasing sense of urgency to pass something, even if it's not perfect.

But while many Republicans are in theory interested in ECA reform, the devil is in the details. Not only are the act itself and the election law issues surrounding it immensely complicated, but the strongest ECA reform bill will require both parties to rein in their own power at the state and federal levels.

—Derek T. Muller (@derektmuller) January 24, 2022

Buy-in from congressional Democratic leadership and the White House is also not guaranteed since they have previously said that ECA reform can complement but not replace or substitute substantive voting rights protections.

In early January, Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer decried a standalone ECA bill as an "unacceptably insufficient and even offensive" idea on the Senate floor. And Democratic Sen. Raphael Warnock dismissed it as " a distraction" and "a cynical political maneuver."

But the stance taken by Democratic leadership may change as they're faced with the possibility of losing their slim majority and, as a result, control of Congress after the 2022 midterms.

On January 10, for example, Senate Majority Whip Dick Durbin said Schumer's opposition to a more narrowly-targeted ECA reform bill was "not a good approach." On January 18, Durbin also told reporters that he was working with Klobuchar and King on their bill and didn't rule out the idea of joining forces with the bipartisan group working on ECA reform. He cautioned, however, that the talks are still fluid.

The lack of a clear deadline is another factor working against legislation being passed.

"I don't think there's an urgency to get this done immediately, in part because we don't have an election where the Electoral Count Act will come into play for three years," GOP Sen. Mitt Romney told reporters in mid-January in reference to the next presidential election.

But if Congress doesn't shore up the law before 2024, it could be too late to stop another near-crisis like 2021.

"I do think that there is a time limit on when this can be done," Seligman said. "Big legislation around issues like this often takes years, I mean, the ECA itself took over a decade. And I don't think we have that kind of time."