- Tropical Storm Imelda, now a tropical depression, swamped southeastern Texas with rainfall up to 43 inches in some areas this week, making it the seventh wettest tropical cyclone in American history.

- Officials say the flooding is worse than that of Hurricane Harvey, which drenched the same area two years ago. At least three people have died.

- This comes just two weeks after record-breaking Hurricane Dorian stalled over the Bahamas, devastating the islands and killing at least 50 people before battering the coasts of Florida, Georgia, and the Carolinas.

- As our planet warms, storms are forecast to become stronger, slower, and wetter.

- Storms with heavy rainfall like Imelda – as well as Hurricane Barry earlier this year and Hurricane Harvey in 2017 – can cause devastating flooding and infrastructure damage even without extreme winds.

- Visit Business Insider’s homepage for more stories.

Tropical Storm Imelda, now a tropical depression, has flooded southeastern Texas with rainfall totals of up to 43 inches. That makes Imelda the seventh-wettest tropical cyclone in US history.

The flooding appears to be worse than that of Hurricane Harvey, and it’s impacting similar areas in and around Houston. Homes that weren’t flooded by Harvey are flooding now, Jefferson County Judge Jeff Branick told the Associated Press on Thursday.

“What I’m sitting in right now makes Harvey look like a little thunderstorm,” Chambers County Sheriff Brian Hawthorne told ABC 13.

Experts called Harvey a “500-year flood,” despite having experienced three previous floods of similar severity in the previous decade. The storm killed 103 people and caused around $125 billion in damages.

Three people have died in Texas due to Imelda floods.

"It's as bad as I've ever seen it," Hawthorne later told NBC News.

The deluge follows Hurricane Dorian, which battered the Bahamas, Florida, Georgia, and the Carolinas just two weeks ago. The record-breaking storm was slow and devastating - it stalled over the Bahamas and pummeled the islands with 185-mph winds and up to 30 inches of rain. The hurricane killed at least 50 people and left 76,000 in need of urgent support.

Bahamas officials say about 2,500 people are still missing.

Read More: Hurricane categories tell only part of the story - here's the real damage storms like Dorian can do

Scientists can't definitely say whether Imelda, Hurricane Dorian, or other individual storms this year are directly caused by climate change, but warming overall makes hurricanes more frequent and devastating than they would otherwise be.

That's because higher water temperatures lead to sea-level rise, which increases the risk of flooding during high tides and in the event of storms surges. Warmer air also holds more atmospheric water vapor, which enables tropical storms to strengthen and unleash more precipitation.

Here's what to know about why storms are getting so much stronger, wetter, and slower.

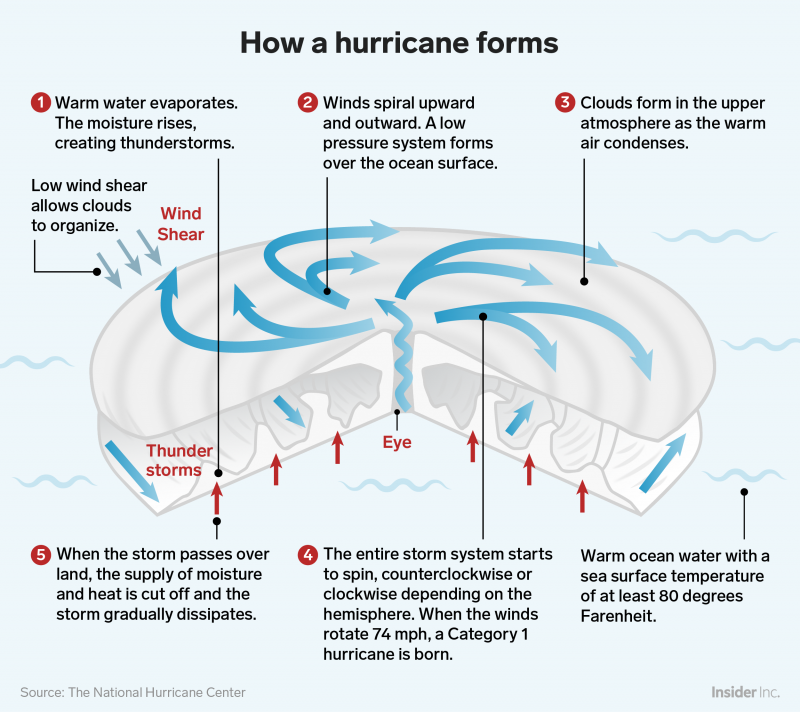

How a hurricane forms

Hurricanes are vast, low-pressure tropical cyclones with wind speeds over 74 mph.

In the Atlantic Ocean, the hurricane season generally runs from June through November, with storm activity peaking around September 10. On average, the Atlantic sees six hurricanes during a season, with three of them developing into major hurricanes. The storms form over warm ocean water near the equator, when sea surface temperature is at least 80 degrees, according to the NHC.

As warm moisture rises, it releases energy, forming thunderstorms. As more thunderstorms are created, the winds spiral upward and outward, creating a vortex. Clouds then form in the upper atmosphere as the warm air condenses.

Foto: sourceShayanne Gal/Business Insider

Foto: sourceShayanne Gal/Business Insider

As the winds churn, an area of low pressure forms over the the ocean's surface. At this point, hurricanes need low wind shear - or a lack of prevailing wind - to form the cyclonic shape associated with a hurricane.

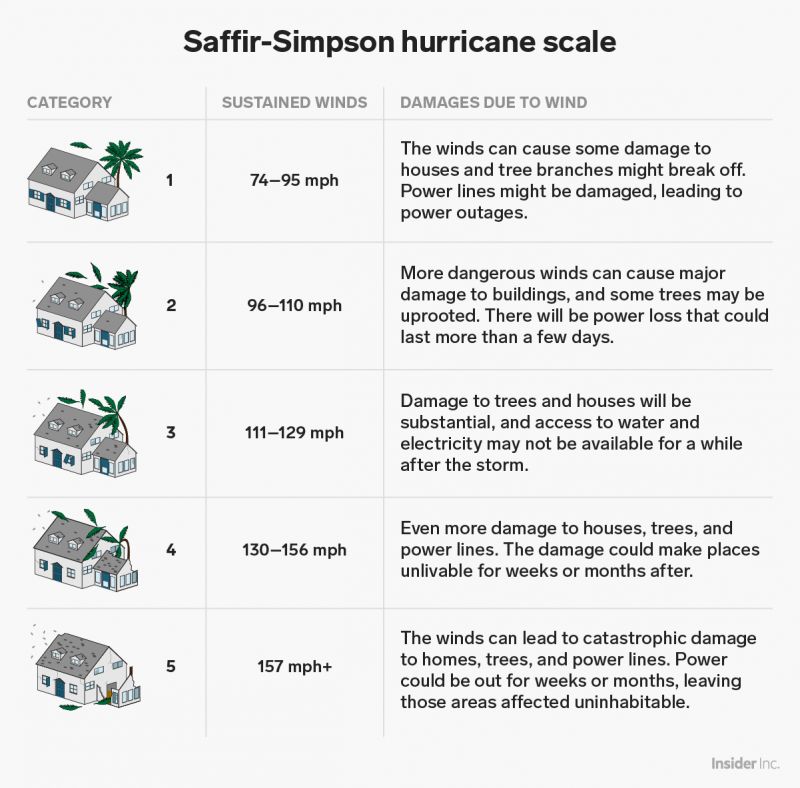

Cyclones start out as tropical depressions like Imelda, with sustained wind speeds below 39 mph. As winds pick up and pass that threshold, the cyclone becomes a tropical storm. Once the wind speed hits 74 mph, the storm is considered a Category 1 hurricane on the Saffir-Simpson scale.

The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) projected a 45% chance that teh 2019 Atlantic hurricane season would see above-average activity. That could mean five to nine hurricanes in the Atlantic, with two to four of those becoming major hurricanes (defined as Category 3 or above, with winds greater than 110 miles per hour).

So far this year, we've seen four hurricanes, two of which - Dorian and Humberto - reached or surpassed Category 3..

Hurricanes are moving more slowly and dropping more rain

Hurricanes use warm water as fuel, so once a hurricane moves over colder water or dry land, it usually weakens and dissipates.

However, because climate change is causing ocean and air temperatures to climb - last year was the hottest on record for the planet's oceans - hurricanes are getting wetter and more sluggish. Over the past 70 years or so, the speed of hurricanes and tropical storms has slowed about 10% on average, according to a 2018 study.

Over land in the North Atlantic and Western North Pacific specifically, storms are moving 20% to 30% more slowly, the study showed.

A slower pace of movement gives a storm more time to lash an area with powerful winds and dump rain, which can exacerbate flood problems. So its effects can wind up feeling more intense.

Hurricane Harvey in 2017 was a prime example of this: After it made landfall, Harvey weakened to a tropical storm, then stalled for days. That allowed the storm to dump unprecedented amounts of rain on the Houston area - scientist Tom Di Liberto described it as the "storm that refused to leave."

Climate scientist Michael Mann previously wrote on Facebook that Hurricane Harvey - which flooded Houston, killed more than 100 people, and caused $125 billion in damages - "was almost certainly more intense than it would have been in the absence of human-caused warming, which means stronger winds, more wind damage, and a larger storm surge."

To make matters worse, a warmer atmosphere can hold more moisture, so a 10% slowdown in a storm's pace could double the amount of rainfall and flooding that an area experiences. The peak rain rates of storms have increased by 30% over the past 60 years - that means up to 4 inches of water can fall in an hour.

"Precipitation responds to global warming by increasing," Angeline Pendergrass, a project scientist at University Corporation for Atmospheric Research, said last year.

Storms are also getting stronger

As ocean temperatures continue to increase, we're also likely to see more severe hurricanes because a storm's wind speed is influenced by the temperature of the water below. A 1-degree Fahrenheit rise in ocean temperature can increase a storm's wind speed by 15 to 20 miles per hour, according to Yale Climate Connections.

"With warmer oceans caused by global warming, we can expect the strongest storms to get stronger," James Elzner, an atmospheric scientist at Florida State University, told Yale.

That can also mean that storms are able to intensify and develop into powerful hurricanes in a shorter time span.

Generally, a strong storm brings a storm surge: an abnormal rise of water above the predicted tide level. This wall of water can flood coastal communities - if a storm's winds are blowing directly toward the shore and the tide is high, storm surges can force water levels to rise as rapidly as a few feet per minute.

Higher sea levels, of course, lead to more destructive storm surges during a hurricane. Such surges are likely to become a more regular threat, since even if we were to cut emissions dramatically starting today, some sea-level rise is inevitable. The planet's oceans absorb 93% of the extra heat that greenhouse gases trap in the atmosphere, and water (like most things) expands when it's heated.

Kevin Loria and Jeremy Berke contributed to an earlier version of this story.