- Coronavirus patients with severe cases often have difficulty breathing.

- That’s because their lungs fill up with fluid, which shows up on a CT scan in the form of white patches called “ground glass.”

- Patients with pneumonia also have these patches, but doctors look for a few more distinct features to diagnose the new coronavirus.

- Visit Business Insider’s homepage for more stories.

Most coronavirus cases are diagnosed through a laboratory test that samples saliva or mucus, but there’s another way to tell whether a person has been infected.

The disease caused by the coronavirus, COVID-19, is a respiratory illness, so patients will often develop a dry cough or difficulty breathing.

Patients with severe cases typically develop fluid in their lungs, similar to those with standard pneumonia. That fluid can be detected on a CT scan, where it shows up in the form of white patches that doctors call “ground glass.”

CT scans are considered less thorough than lab tests, but they offer a quicker way to diagnose patients – or help identify the virus in people who died before a test could be administered.

Here's what physicians look for to detect the virus on a scan.

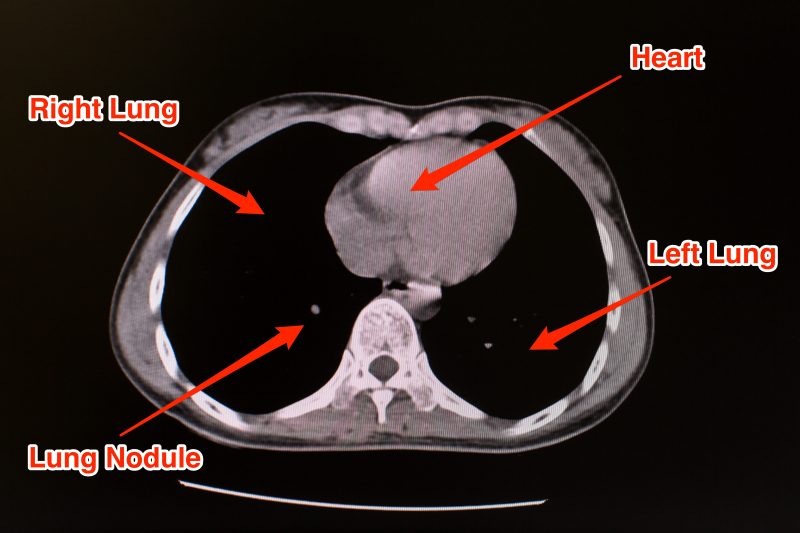

Normal lungs should appear black on a CT scan.

It's common to have small masses of tissue, or lung nodules, that show up as tiny white dots.

But coronavirus scans tend to have white patches that radiologists refer to as "ground glass opacity."

"It kind of looks like faint glass that has been ground up," Paras Lakhani, a radiologist at Thomas Jefferson University, told Business Insider. "What it represents is fluid in the lung spaces."

On its own, Lakhani said, ground glass isn't particularly helpful for identifying a coronavirus.

"You can see it with all types of infections - bacterial, viral, or sometimes even non-infectious causes," Lakhani said. "Even vaping could sometimes appear this way."

But the patches are significant, he added, when they extend to the edges of the patient's lungs.

"That's something we don't often see," Lakhani said. "We saw that with severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) and we saw that with Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS)."

Both SARS and MERS are also coronaviruses. An outbreak of the former in China resulted in 8,000 cases and 774 deaths from November 2002 to July 2003.

An analysis of nearly 140 coronavirus scans said patches of ground glass on both lungs were a hallmark of the virus.

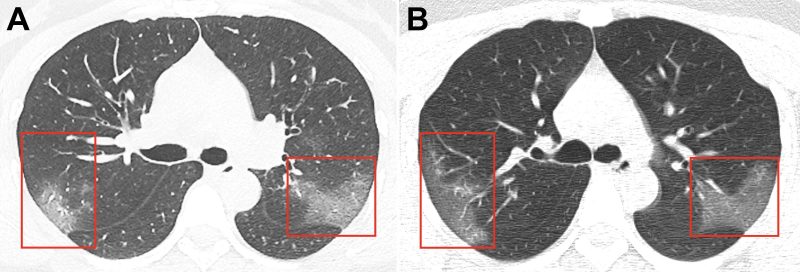

Researchers analyzed scans from patients at the Zhongnan Hospital of Wuhan University, the majority of whom were older men with preexisting health problems. The images above are scans from a 52-year-old patient.

The first group of scans (group A) were taken on January 7, five days after the patient started displaying symptoms. They show patches of ground glass at the bottom of both lungs.

The man was put on life support from January 7 to 12. After that, his condition seemed to improve. The second set of scans (group B), taken January 21, show that many of the white patches either shrunk or disappeared.

Many patients tended to worsen quickly. Their ground-glass patches became more pronounced after a few days.

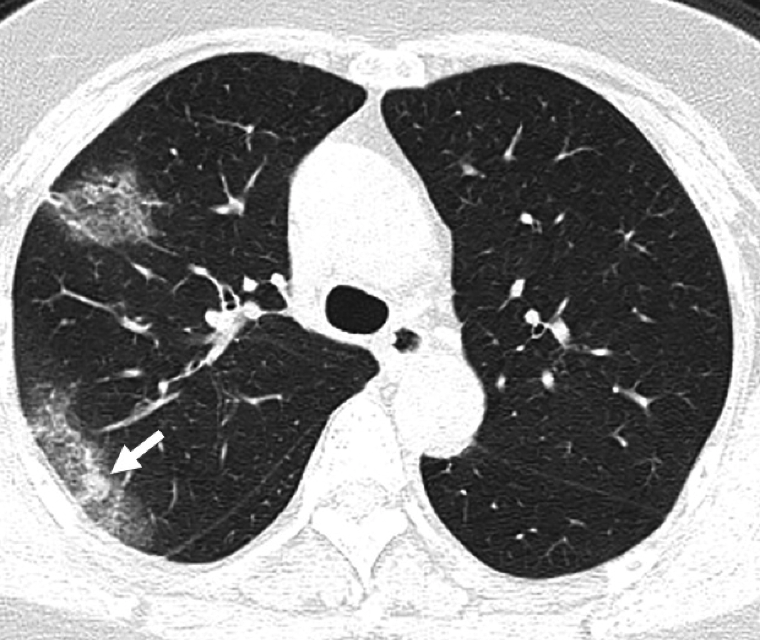

A 33-year-old woman arrived at a hospital in Lanzhou, China with a fever and five-day-old cough. Her temperature was 102 degrees Fahrenheit, her breathing was "coarse," and she had a low white blood cell count - a sign of infection.

In an initial CT scan, researchers at the First Hospital of Lanzhou University found the recognizable white ground-glass patches in the lower corner of her lungs.

They gave her a protein used to treat viral infections, called interferon. But three days later - and further into her treatment - the patches were more pronounced. Lakhani said the same thing occurred in SARS patients.

"If you didn't know about this outbreak, you'd read the scan and you would just say, 'Okay, this patient has pneumonia,' because that's the most common thing we see," he said.

But Lakhani added that "pneumonia usually doesn't rapidly progress," so it could be ruled out in this case.

Scans from a 27-year-old woman who worked in Wuhan showed a "ground-glass halo" — white patches that surround a small nodule.

Researchers at Anhui Medical University in Hefei, China examined the woman after she was admitted for a fever and cough. Her breathing was also coarse. The "ground-glass halo" they found can be a distinguishing feature of viral infections and pneumonia, the researchers said.

After four days in the hospital, the nodule on the patient's right lung had grown.

Some patients also exhibited a "crazy-paving pattern," which refers to little lines inside the ground-glass patches.

A study of 21 patients across three Chinese provinces found four patients with a "crazy-paving pattern" in their scans.

"It almost looks like a cobblestone road," Lakhani said. "Sometimes when we see it, it's everywhere - the whole lung has it. But to see it in a few small areas is a little less common, a little more unusual."

The pattern has also appeared in some SARS and MERS scans, he said.

Another study of patients who recovered from the coronavirus suggested that crazy-paving could be common among patients with milder cases.

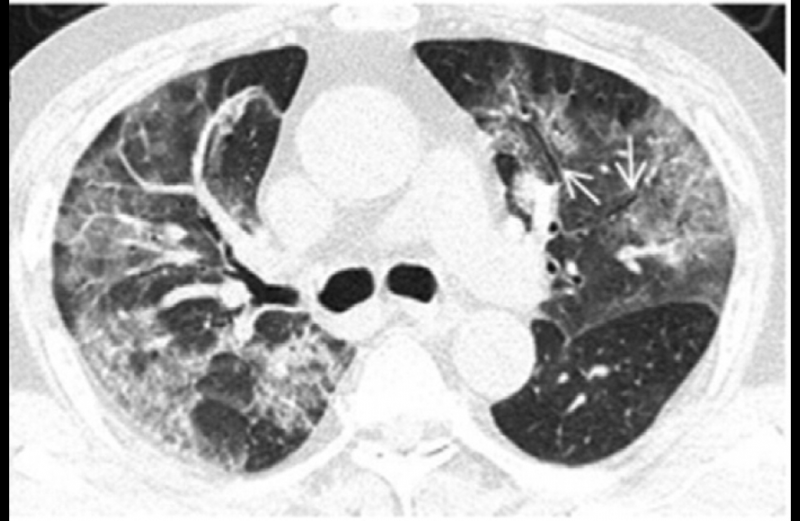

A Shanghai study also identified a mesh-like pattern called "reticulation," which is visible in this scan of a 75-year-old man.

Researchers at the Shanghai Public Health Clinical Center analyzed this patient's scan three days after the man was admitted to the hospital. In addition to ground glass, it shows a web-like "reticulation" pattern - a sign of lung damage commonly associated with acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS).

A recent study in The Lancet found that the coronavirus can lead to ARDS, which is often fatal.

According to the Shanghai researchers, 22% of the 50 patients they looked at displayed reticulation on their scans. Around 77% had ground-glass patches, while nearly 60% had consolidation - lung tissue that filled with liquid instead of air.

The Shanghai researchers ultimately determined that three components are needed to diagnose a coronavirus patient: fever and/or cough, ground-glass patches in both lungs, and a history of exposure to the virus.

But the coronavirus doesn't always show up in scans right away.

"We can't rely on CT alone to fully exclude presence of the virus," Michael Chung, the lead author of the Lanzhou study, said on February 3.

Lakhani said CT scans are "one of four or five things" needed to make a diagnosis, along with symptoms, clinical history, the progression of the disease, and the laboratory test.

Read more about the coronavirus: