- China has the largest high-speed railway in the world, with 15,500 miles of track and most major cities covered by the network.

- I recently took China’s fastest “G” train from Beijing to the northwestern city of Xi’an, which cuts an 11-hour journey – roughly the distance between New York and Chicago – to 4.5 hours.

- I found the experience delightful, with relatively cheap tickets, painless security, comfortable seats, air-conditioned cabins, and plenty of legroom.

- It left me thinking about how far behind US infrastructure has become, when most comparable journeys still require expensive and tiring air travel.

Traveling to China can often feel like visiting the future. The cities stretch out for what seems like forever, while new skyscrapers, bridges, and futuristically designed landmarks spring up every year.

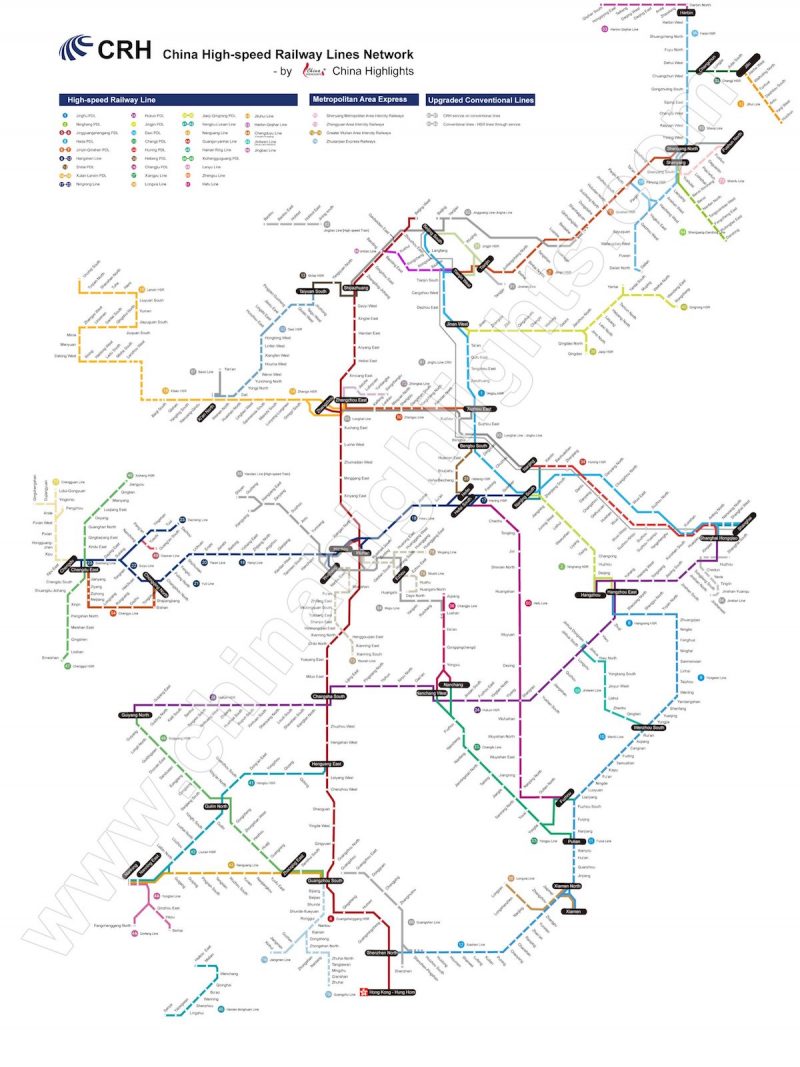

Nowhere is this feeling more apparent than when you encounter China’s high-speed railway network. At 15,500 miles, the country’s “bullet train” is the world’s largest.

And it’s getting larger.

The China Railway Corp., the country's government-owned train operator, is getting close to finishing the Guangzhou-Shenzhen-Hong Kong Express Rail Link, a high-speed rail line spanning more than 80 miles. And the country's plan is to create an extended network that covers 24,000 miles and connects all cities with a population greater than 500,000.

Currently, there are over 100 cities in China with a population greater than 1 million, a figure projected to grow to 221 cities by 2025.

The practical result of this is that you can pretty much travel in anywhere in China via high-speed rail. It's usually comparable in speed to air travel (once you factor in security lines and check-in) and far more convenient, as I found on a recent trip to China.

I had made plans to travel from Beijing to Xi'an, the capital of northwestern Shaanxi province and the imperial capital of China for centuries.

The distance between the two cities is around 746 miles, making it slightly more than two hours by plane, 11 hours by car, and anywhere between 11.5 hours and 17.5 hours on a regular train.

On China's top-of-the-line "bullet train," the journey takes 4.5 hours.

If I wanted to travel a comparable distance in the US by train - at 712 miles, New York to Chicago is the closest - it would take 22 hours, with a transfer in Washington, DC. And that's with traveling on Amtrak's Acela Express, currently the fastest train in the US with a speed up to 214 km/h (150 mph).

Traveling on one of China's fastest bullet trains is an entirely different experience:

I arrived at Beijing West Railway station a little over an hour before my train at 2:00 p.m. Built in 1996 and expanded in 2000, the railway station is the second largest in Asia, serving up to 400,000 people a day. It was very busy when I arrived.

China's railway network served nearly 3 billion passenger rides in 2016, a figure that has increased by about 10% each year. It's little surprise. The nationwide system covers 15,500 miles, a figure made more impressive when you consider the first line was built in 2008 for the Beijing Olympics.

China's first high-speed rail line was a single 70-mile demonstration line built specifically for the Beijing Olympics in 2008.

The country has set aside $550 billion in its current five-year plan (2016-2020) for expanding China's railway system, with an emphasis on high-speed rail.

The massive development plan hasn't all gone smoothly. The country's top economic planning agency found that many cities and provinces were building far too expensive and ostentatious train stations far from city centers in an effort to get in on the development extravaganza, Beijing-based media company Caixin reported earlier this month.

One railway expert told Caixin that local governments have been developing the stations far from city centers in the hopes that the facilities, which they want to link with the high-speed rail, can boost development and real-estate prices.

I had bought my rail ticket on CTrip, China's top e-travel agency. But for some reason, you still have to pick up your ticket in person, which requires navigating to the ticket lines and finding the one counter designated for English speakers. If there's one aspect of the high-speed rail system that could be improved, it's ditching hard tickets for e-tickets. But, knowing China's obsessive adoption of mobile phones and QR codes, I'm sure it won't be long.

Tip: Instead of using CTrip's website, book your rail ticket on the company's mobile Trip app. In November last year, CTrip acquired US online travel agency Trip.com and rebranded Trip as their global brand app.

It's far more user-friendly than the CTrip website (Chinese tech still has a lot to learn about UX).

To pick up your ticket, you have navigate to the first-floor entrance from the outside and then head up escalators with ticket in hand. Unfortunately, the primary taxi drop-off is on the second floor of the station, so you have to lug your bag downstairs. It's a pain.

To enter the station proper, you have to present your ticket and passport (or Chinese national ID) and put your bags through an x-ray machine and step through a metal detector. All that security happens right at the entrances, which gives a nice peace-of-mind considering recent terror attacks in transit hubs across the world.

The Beijing West Station is over 20 years old at this point and a bit shabby when compared to the country's other railway stations. But it's fairly easy to navigate once you get inside. Match the train number on your ticket to the numbers on the platforms and you're ready to go.

Most newer railway stations in China look more like airports than train stations. This is the one I encountered in Xi’an, a city of 8.7 million people. It had high ceilings, futuristic architecture, and nicely spaced gates for the platforms.

By comparison, Beijing West was very cramped. And the Friday afternoon train for Xi'an was packed. Most high-speed trains from Beijing to Xi'an take between 5 and 6 hours because of stops along the way. But the express I caught cut the journey to 4.5 hours.

High-speed trains have first- and second-class seats. Some have business class. But if there was a separate line for Business class or First class, I didn't see it. Like most lines in China, it was a somewhat chaotic crush to the front.

A lot of people decided to sit it out and wait. The seats are all assigned like an airplane, so it's probably not worth it to rush. But I'm a worrywart and it was my first time.

When you get to the front of the line, you scan your ticket in the card reader. It looked like there was an option for a tap card for frequent riders, but I didn't see anyone using it.

It's pretty amazing when you head down the platform and see rows of sleek "bullet trains" headed all over the country. About a week after I took this train, I happened to be standing on a train platform in a smaller city when a bullet train blew by at full speed. The whoosh of the train nearly knocked me onto the ground.

I found my carriage, four, and headed inside. China has multiple train classes. High-speed trains include the G-train I was to ride (usually 300 km/h, though there is the new Fuxing type that hits 350 km/h, about 185 mph), D-trains (250 km/h, or about 155 mph) and C-trains (200 km/h, or about 124 mph). There are also half a dozen other regular-speed trains.

China Travel Guide has an extensive breakdown of the different train types and ticket class types »

The second-class cabin looks more or less like an airplane. One side has three seats across and the other has two. The overhead compartments can handle suitcases somewhat larger than airplane carry-on size, but there is a closet at the end of the carriage for larger items. I did see a train attendant tell one passenger to take their bag down because it was too big.

The train got up to around 200 km/h (124 mph) within minutes of departure. At that speed, it's already faster than most trains in the US.

My ticket cost around $81 for a second-class seat. First class was around $130. Prices vary depending on the train, the route, and the day. A second-class ticket from Beijing to Shanghai (819 miles) costs around $88, while Beijing to Kunming (at 1659 miles, the longest route) costs around $176.

Most "bullet trains" have a dining car, but it's not like the dining cars of old. Rather than cook onsite, they offer prepackaged microwaveable meals. On the Beijing-Xi'an train I took, there was no dining car at all. Instead, a train attendant came by with a trolley selling snacks, drinks, and instant noodles.

Source: China Travel Guide (Check this out for more info on the food on China's trains.)

Thankfully, the Beijing train station had a wide variety of fast-food and fast-casual options. I got pork katsu over rice from Yoshinoya, a popular Japanese chain.

Though I opted not to splurge for first class, I was very happy with my seat. It was big and comfortable, with lots of legroom. Even with my backpack in front of me, I was able to spread my legs out fully. First class limits the rows to two seats across, while business class has fully reclinable seats.

Every carriage has a hot-water dispenser. Chinese people drink a lot of tea. This came in handy when I took the train back to Beijing and had to eat instant noodles. As for the question you are all wondering: The bathrooms were Western-style and pretty clean. This was not the case when I took a regular-speed train.

The scenery between Beijing and Xi'an is not that stunning, but it is cool to see it blowing by.

A lot of people seemed to enjoy killing the time by hanging out in the space between the carriages. People did this in the regular-speed train I took, except they used the space to chain-smoke cigarettes. This didn't happen on the bullet train.

It wasn't long before the train kicked up to its top-end speed of 307 km/h (190 mph).

You could definitely feel the higher speed, though it's probably a credit to the engineering that I didn't feel it too much. I only really noticed the speed when I looked out the window and saw the scenery whizzing by.

I worked on my laptop for several hours to kill the time. Fortunately, there was a power outlet below my seat so I could plug in when the battery died. But there seemed to be only one power outlet per row. So if you get unlucky, you'll have to make friends with your neighbor.

After one stop about halfway through the journey, where a few people got off, we continued on to Xi'an. As we approached, people started to gather their stuff and get ready to leave.

When you get off the train, you have to scan your ticket again to leave the station. Like most of China's bullet trains, the Xi'an train platform opens directly into the metro. It makes for a seamless experience.

After riding China's bullet trains back and forth across the country, I couldn't help feel as if the US is being left behind, at least when it comes to transit.

During my one month in China, I started by taking planes across the country - three in total. But about halfway through the trip, I realized how dead simple and convenient the bullet trains were. I ended up taking four bullet trains in total.

The last one, from Zhengzhou to Shenzhen, covered a distance of 992 miles, or about the distance between New York and Jacksonville, Florida. The trip took a little over six hours.

The prices of the train tickets topped out around $100 from what I saw, which was the most mind-blowing thing for me. Train tickets on the only remotely high-speed train in the US, the Acela Express from New York to Washington, DC, frequently go for more than $200.

Experts have said that the reason for the lack of investment in the US in high-speed rail is its large land size and the relative distance between major cities. The lower population density in the US, when compared to China, the EU, or Japan, is also cited.

While it's hard to imagine a rail network as extensive as China's or a rail line connecting New York with Los Angeles, it seems crazy that, at this point, the best high-speed offering in China is eons more advanced and effective than its US equivalent.