- The Kincade Fire ignited in Sonoma County, California, on October 23 and has burned 76,825 acres. It was 60% contained as of Thursday morning.

- The fire forced nearly 200,000 people to evacuate their homes as powerful winds enabled it to spread quickly. Evacuees began returning home on Wednesday.

- The blaze has destroyed 282 structures, including 141 homes. Four first responders have been injured.

- Pacific Gas and Electric (PG&E) told state regulators that a broken jumper cable on one of its transmission towers may have caused the fire.

- PG&E cut power for at least 973,000 customers in its largest-ever blackout to reduce further wildfire risk.

- As the climate warms, California’s wildfire season is getting longer, and weather conditions that bring a risk of wildfires are becoming more common.

- Visit Insider’s homepage for more stories.

The Kincade Fire, which ignited in California’s Sonoma County on October 23, has torn through an estimated 76,825 acres – an area more than twice the size of San Francisco.

The blaze forced about 180,000 people to flee a large area from Mercuryville to Santa Rosa, according to the Sonoma County Sheriff’s Office. Evacuees started returning home on Wednesday night, though many found nothing but rubble where their houses once stood.

“It’s crazy, just an incredibly empty feeling,” Ken Schmidt-Peterson, who lost his family home in the fire, told local news station KTVU. “I did as much as I could do to prevent it from coming up here but the wind was blowing so hard.”

So far, the blaze has destroyed 282 structures, including 141 homes, and left 50 damaged. The blaze was 60% contained as of Thursday morning.

The combination of powerful winds - gusts of up to 102 mph were recorded in the area over the weekend, according to the National Weather Service (NWS) - and dry, hot weather conditions enabled the flames to spread quickly.

California Gov. Gavin Newsom to declare a statewide emergency on Sunday.

A break in the windy weather on Wednesday allowed firefighters to make significant progress overnight, according to the California Department of Forestry and Fire Protection (Cal Fire).

"There is a lot of optimism that we have turned the corner for the better on this fire," Cal Fire Division Chief Jonathan Cox said in a press conference.

Cal Fire reported that four first responders have been injured.

In the week since the fire began, utility company Pacific Gas and Electric (PG&E) has cut power to hundreds of thousands of customers in two rounds of outages - a strategy meant to minimize a risk that live wires could spark and start more fires. Over the weekend, at least 973,000 customers were left in the dark; it was the company's largest-ever intentional outage, according to the San Francisco Chronicle.

On Wednesday night, PG&E reported that it had restored power to 95% of those customers, with 53,000 customers remaining without electricity.

"Not only are we in the dark, it's almost like we are completely shut off from the world and that makes it even more terrifying," Annette Carter, a resident of the northern California town of Clearlake, told the Los Angeles Times. "I can handle a lot of stuff, but my kids being in fear and not being able to reach out to the world and find out what's going on ... that's problematic."

In the Bay Area, meanwhile, low evening temperatures made the outage especially challenging.

"The thing is the cold," Eliana Rubin, a Clearlake resident who cared for her newborn son by candlelight for four nights, told the LA Times. "I am, like, folding him under the blankets."

PG&E CEO Bill Johnson has said that Californians should expect these types of preemptive outages for another 10 years.

The Kincade Fire may have started at one of PG&E's transmission towers

PG&E told regulators last week that the blaze may have been caused by a broken jumper cable on one of the company's transmission towers. Sparking PG&E wires also started last year's record-breaking Camp Fire, which razed more than 18,800 structures and killed 86 people in November.

In a preliminary report, PG&E said it learned of the issue with its broken cable at 9:20 p.m. local time on October 23, when it responded to a problem with a 230,000-volt line that forced a power outage. When PG&E crews arrived at the transmission tower, they found that Cal Fire had taped off an area at the tower's base. Cal Fire personnel pointed out the broken jumper cable.

In the days before the blaze, PG&E had cut power to hundreds of thousands of Californians in parts of Sonoma County, including Geyserville, where the Kincade Fire started. But the company opted to only make targeted power cuts and keep high-voltage lines running in order to continue providing power to other areas. The spark occurred at a tower that had been kept online.

On Friday, Gov. Newsom vowed to force PG&E to make improvements to minimize outages and avoid sparking cables in the future.

"We should not have to be here - years and years of greed, years and years of mismanagement, particularly with the largest investor-owned utility in the state of California, PG&E," he said, adding, "We will do everything in our power to restructure PG&E so it is a completely different entity when they get out of bankruptcy by June 30th of next year. We will hold them accountable for the business interruption and costs associated with these blackouts."

In a Tuesday press conference, Gov. Newsom said that PG&E had agreed to offer customers some compensation for the recent blackouts, though he did not offer further details.

"We thought this was probably a pretty good idea to show a little recognition to our customers," Johnson said on Tuesday. "As to how that gets done, the mechanics, I don't know the answer to that. We'll be getting around to that after this event."

Powerful winds have spread fires across California

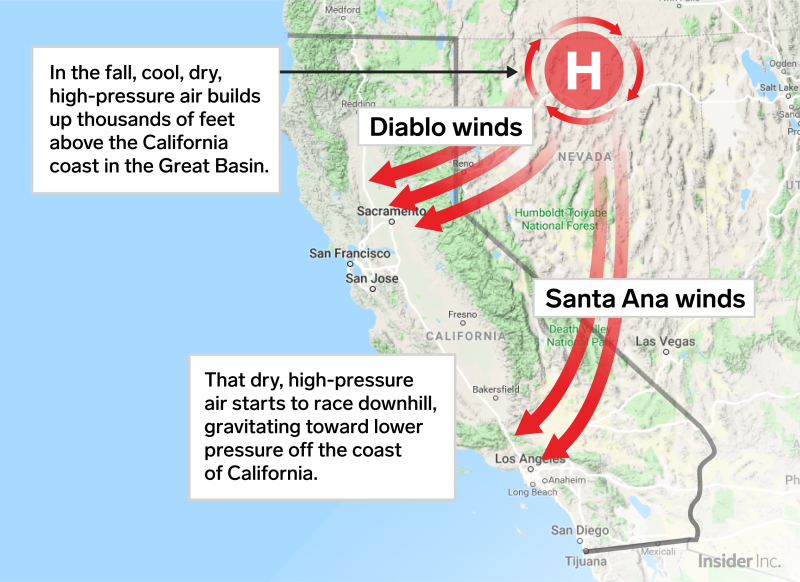

Strong winds - called Santa Ana winds in southern California and Diablo winds in the north - have heightened fire risk across the state.

The gusts blow down from neighboring mountains toward the southern California coast during the fall and winter. They're typically fiercest in the fall, before the first rains of the season arrive.

The Diablo winds contributed to the Kincade Fire's rapid spread, according to AccuWeather meteorologist Alex Sosnowski.

"The wind almost always brings a great surge in temperature and dry air," he said.

The connection between climate change and wildfires

Individual wildfires can't be directly attributed to climate change, but accelerated warming increases their likelihood.

"Climate change, with rising temperatures and shifts in precipitation patterns, is amplifying the risk of wildfires and prolonging the season," the World Meteorological Organization (WMO) said in a July release.

That's because warming leads winter snow to melt sooner in the annual cycle, and hotter air sucks away the moisture from trees and soil, leading to dryer land. This has led wildfire season to get longer: The average wildfire season in the western US lasts 78 days longer than it did 50 years ago, according to the Center for Climate and Energy Solutions.

"We're really seeing that window expanding, not only earlier into the spring but also later into the fall as things stay drier, longer," Leah Quinn-Davidson, a fire adviser for Humboldt County whose own power has been shut off in the blackouts, previously told Business Insider. "We are at the point where we are in a crisis."

That warming trend is especially apparent this year. July was the hottest month ever recorded, and 2019 overall is on pace to be the third-hottest on record globally, according to Climate Central.

Decreased rainfall also makes for parched forests that are prone to burning.

A recent study found that the portion of California that burns from wildfires every year has increased more than five-fold since 1972. Nine of the 10 biggest fires in the state's history have occurred since the year 2003.

In the western US more broadly, large wildfires now burn more than twice the area they did in 1970.

"No matter how hard we try, the fires are going to keep getting bigger, and the reason is really clear," climatologist Park Williams told Columbia University's Center for Climate and Life. "Climate is really running the show in terms of what burns."