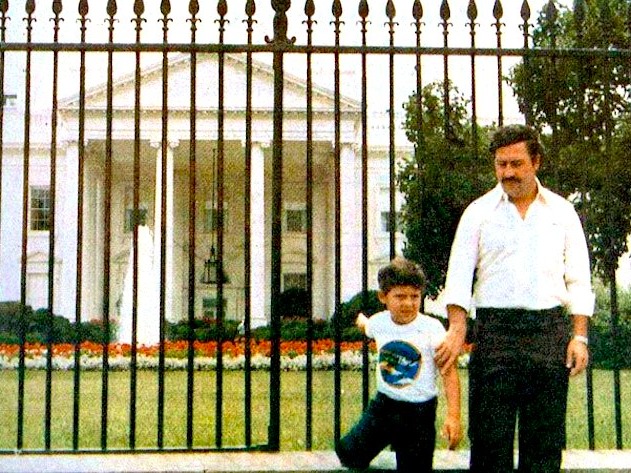

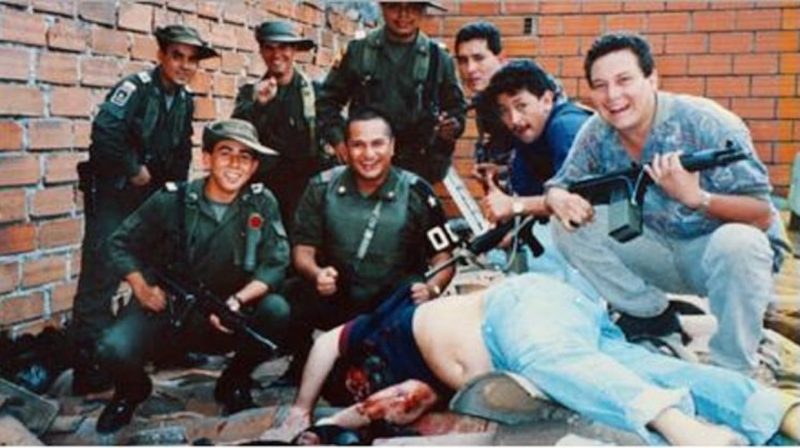

Medellin cartel chief Pablo Escobar had his life snuffed out on December 2, 1993, but his reputation as a brutal and prolific drug trafficker has lived on.

Though he reigned over the Colombian underworld for years, he was not the only game in town.

Chief among his rivals was the Cali cartel, based in the city of the same name southwest of Escobar’s stronghold in Medellin and run by two brothers, Miguel and Gilberto Rodriguez Orejuela.

It’s suspected the two cartels cooperated to some extent in the 1980s, organizing an armed group to fight kidnappers and working to stabilize the drug market and divide up territory in the US – the Medellin cartel took Miami and South Florida, while the Cali cartel controlled New York City and parts of the northeast.

But they remained rivals, and the cartels fought a vicious turf war in Colombia, even as Escobar and his partners waged a war against the Colombian state to fend off arrest and extradition.

Cali cartel leaders were behind efforts to kill Escobar, hiring mercenaries in a failed attempt on his life in 1989 and reportedly supporting a paramilitary group that ran his Medellin cartel to ground in the early 1990s.

Like Escobar, the Cali traffickers had been operating since the 1970s, but their organization didn't reach its zenith until after his death. At the height of its power it sent hundreds of tons of cocaine to the US and laundered billions of dollars in drug money. It was reportedly responsible for 80% of the world's cocaine trade at one point.

Like rivals in any other industry, the Cali cartel leadership took lessons from Escobar's rise and fall.

"What we noticed was that Cali cartel had learned from the Medellin cartel not to make those types of mistakes," Javier Peña, a US Drug Enforcement Administration who worked on both the Escobar and the Cali cartel cases, said on The Cipher Brief podcast.

"For example, I call the Medellin cartel 'wild, wild west'; Cali cartel was more business-like. They were more organized; they had more business savvy. They had more sophisticated accountants," added Peña, who was been portrayed by actor Pedro Pascal on three seasons of the Netflix show "Narcos."

Gilberto Rodriguez Orejuela, nicknamed "the Chess Player," in particular earned a reputation for being business-oriented, preferring bribery to violence.

The Rodriguez Orejuela brothers and their partners, posing as businessmen and investing in Colombian and US companies, earned a level of public respect for their behavior (though they were always willing to resort to violence). Gilberto called himself an "honest drugstore magnate," referring to a chain of pharmacies his family owned.

"The cartels, I think, learned a valuable lesson with what Pablo Escobar was doing with wholesale violence, just basically narco terrorism," Mike Vigil, former chief of international operations for the DEA, told Business Insider in an interview earlier this year about the evolution of Colombia's criminal organizations.

"They learned a valuable lesson that the more violence you generate against the government, against the citizens, the more of a target you're going to become by the government and the international community," Vigil said.

The "Cali cartel was harder [to track] because of the network they had. They used more professional-type accountants. They had education in the United States ... and Cali was also more sophisticated in their smuggling method," Peña said.

While the Medellin cartel was known for bulk smuggling, particularly with planes flying into Florida, the Cali cartel "would hide a lot of coke inside big cargo-type containers, inside cement, inside heavy machinery, which was very hard to detect," Peña added. Such methods persist among traffickers in Colombia and elsewhere.

The Cali cartel was known to operate "cells" in US cities - Miami, New York, and Houston in particularly during the late 1990s. A regional manager would lead the cell, hiring submanagers to handle jobs like transport, storage, and distribution of drugs as well as collection of drug-sale proceeds.

But the Cali cartel's growth and assertiveness still earned it attention from the US and Colombian governments.

Officials in Washington put pressure on their Colombian counterparts to bring down the Rodriguez Orejuela brothers and their partners in the early and mid-1990s, after years of what seemed to be little official action against their activities.

Cali cartel activity in the US in the early 1990s was particularly brazen at times, as it used violence to protect its interest on US soil.

Cartel cofounder Jose Santacruz Londono was accused of ordering an assassination over a business deal gone bad in summer 1991. That same year, he reportedly ordered the killing of a Cuban-born New York journalist whose stories had raised the cartel's ire.

"They are trying to do things in this country similar to what they do in Colombia," the-DEA chief Thomas A. Constantine said in early 1995.

The period between 1994 and 1995 was especially concerning for the US, after the release of recordings of people identified as Cali cartel leaders discussing millions of dollars of contributions to the presidential campaign of Ernesto Samper. The revelations damaged US-Colombia relations and led to Washington revoking Samper's visa.

In a letter released in 2000 purportedly written by Gilberto and Miguel, they admitted to giving millions to the campaign. Members of Samper's presidential campaign were eventually convicted in relation to the drug money, but Samper, president from 1994 to 1998, was cleared by Colombia's Congress.

Numerous high-level Cali cartel figures were arrested in 1995, however, including Jorge Eliecer Rodriguez Orejuela in March and cartel cofounder Jose Santacruz Londono in July.

That summer also saw the downfall of the Rodriguez Orejuela brothers themselves.

Then-President Ernesto Samper called the June arrest of Gilberto - caught hiding in a secret compartment in a luxurious Cali home - "the beginning of the end for the Cali cartel."

When Miguel was arrested two months later - caught in his underwear before he could hide in a secret closet - national police chief Jose Serrano said, "The Cali cartel died today."

The Medellin and Cali cartels continued to exist in some form in the years after their respective leaders' demise, but Colombian criminal organizations continued to evolve in response to a changing drug market and ongoing pressure from authorities.

In 1997, US officials said there were more cartel operatives than ever in South Florida and levels of cocaine coming into the area were higher than ever.

A DEA spokeswoman called Miami "the North American headquarters for the South American cartels" in early 1997.

"They haven't gone away," she added. "They've just changed their profile."

In Colombia, the reign of large, hierarchical cartels gave way to that of paramilitary groups, who were eventually replaced by more criminal groups, or "bandas criminales," that are more compartmentalized, dispersed, and autonomous than their predecessors.

"The criminal underworld in Colombia has become very much like traditional organized crime under, like, Carlo Gambino, where they try to be invisible," Vigil told Business Insider.