Dutch innovator Boyan Slat’s audacious plan to clear plastic from the marine area known as the “great Pacific garbage patch” is undergoing some major design changes. But the 22-year-old tells Business Insider that the first cleanup array is set to launch sooner than expected.

“Instead of late 2020, the cleanup will now start in just 12 months from now, and parts of it are already in production,” Slat says.

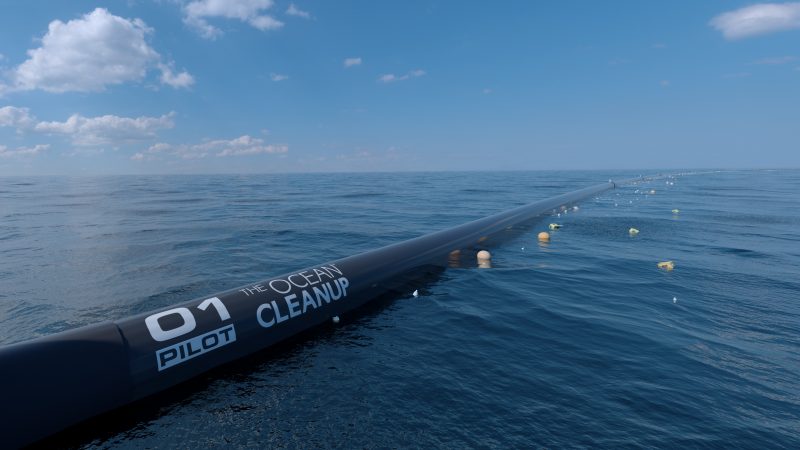

Slat’s nonprofit, The Ocean Cleanup, plans to try to install systems to remove vast quantities of plastic from the Pacific ocean. The systems are designed to float on the surface of an area that collects pollution from around the world, and skim plastic off the top layer of water.

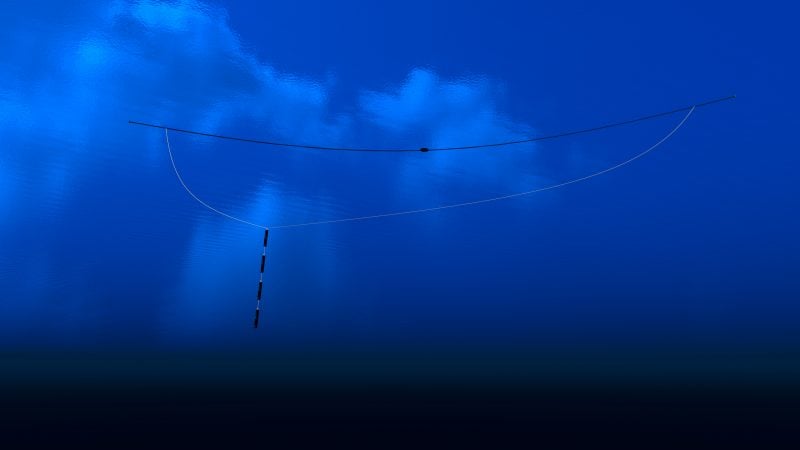

Slat’s original design involved mooring a massive plastic-collecting trap to the seabed 4.5 kilometers below – a controversial plan that gave rise to concerns among scientists. Slat says the group now plans to deploy smaller arrays with underwater “anchors” that drift about 600 meters beneath the surface. Theoretically, the anchors will hold the plastic collecting systems in the spots where they can collect garbage most efficiently.

The team showed off the anchors at their most recent press conference on May 11.

"These systems will automatically drift or gravitate to where the plastic is," Slat says. "Instead of us being able to clean up 42% of the patch in 10 years, we can now clean up 50% of the patch in five years."

Slat says models of the new system show improved efficiency, but no tests have been run with an actual array in the sea to verify those claims. Slat also says the design change helped convince a group of donors to give $21.7 million to the nonprofit, raising its total funding since 2013 to $31.5 million. The new donors include San Francisco-based philanthropists Marc and Lynne Benioff, an anonymous donor, and Peter Thiel, among others.

But will it work?

A swirling vortex of garbage

The Ocean Cleanup hopes to address a problem that's serious and complex. Plastic garbage from all over the globe flows into the world's oceans, then over time gets carried by currents to five regions of the ocean known as gyres - natural gathering points for marine debris.

These "garbage patches" don't look like islands of plastic - many people who have sailed through them say you don't see much trash while passing through. But the plastic is there, and it's ugly and dangerous. Animals like sea turtles, seals, and birds eat it, which poisons them. And as it breaks down into little particles, the microplastic debris ends up in fish that often enter our own food supply.

When Slat first suggested that a 65-mile floating V-shaped array could collect plastic floating near the surface and funnel it to a collection point, the idea gained traction. He gave a viral 2012 TEDx talk about the plan, but a number of marine scientists were skeptical about the unproven plan to create the "largest offshore structure ever assembled."

Slat's team has only tested the new system in labs and simulations, so it's still theoretical. But the advantages offered by the smaller, one-kilometer-long arrays may help assuage some concerns, though it may create just as many new ones. Each can function as an individual test to see how well the systems are working; they're probably easier to fix or remove if something goes wrong; and it's simpler financially to scale up construction over time, building and launching arrays once there's enough funding.

Slat also claims that these smaller systems will be more efficient - it's "better, faster, and cheaper," he says.

Reasons for skepticism

Still, the absence of real-world evidence that the arrays will work is likely to raise questions among marine scientists and oceanographers who have previously expressed doubts about The Ocean Cleanup's plans. The forces of the ocean are strong, and no one knows how well these systems will hold up when subjected to storms or extreme currents. If they break, they could contribute to the trash problem.

Scientists have also expressed concerns that the systems may attract fish and other marine life that might then ingest the plastic. Plus, it's hard to know how much of the plastic that gets collected will actually be recyclable; and some researchers say the trash is deeper and will be harder to collect than The Ocean Cleanup team anticipates.

Furthermore, much ocean garbage sits too deep for the arrays to collect, Nancy Wallace, director of the Marine Debris Program at the US National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, told the Associated Press. But she says the project should be praised for bringing attention to this issue.

"The more people are aware of it, the more they will be concerned about it," Wallace tells the AP. "My hope is that the next step is to say 'what can I do to stop it?' and that's where prevention comes in."

But there may be more efficient ways to accomplish The Ocean Cleanup's goals. One of the project's most prominent critics, oceanographer Kim Martini, has argued that the arrays should be placed off the shores where most plastic enters the ocean in the first place.

Other groups simply attempt to collect plastic before it goes out to sea. The Ocean Conservancy has collected more than 200 million pounds of trash from beaches, and Baltimore has a trash-collecting water wheel that has trapped almost 1.5 million pounds of trash in the Inner Harbor since May 2014.

True, these approaches don't capture the plastic that's already traveled out through ocean. If an array works as the team at The Ocean Cleanup hopes, therefore, it would be a fantastic, impressive achievement. But scientists remain skeptical. The early results of Slat's audacious plan should become available next year - if he sticks to this new schedule.