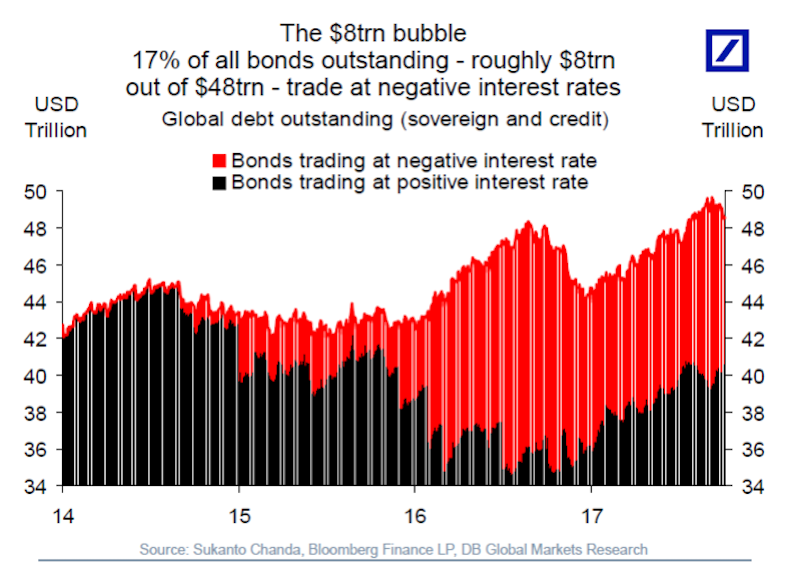

For all the hype about bitcoin, far more investors are exposed to an $8 trillion bubble in financial markets.

It’s all the government and corporate bonds that still have negative yields eight years after the financial crisis, according to Torsten Sløk, the chief international economist at Deutsche Bank.

This is not normal, and it is a legacy of the amount of stimulus that global central banks had to pump into their economies after the recession, partly by buying massive amounts of government bonds. Investors bought these bonds for their perceived safety and because some institutions like banks were required to.

All this demand raised the bonds’ prices, pushing their yields below zero in Japan and in some parts of Europe.

"These $8trn in negative yielding assets have forced investors around the world into all kinds of other asset classes such as IG credit, loans, mortgages, HY bonds, equities, and even emerging markets fixed income and equities," Sløk said in a note on Friday.

One loose proxy for how starved investors are for yield is in the comparison between the riskiest European corporate bonds and the secure 10-year yield. According to Bank of America Merrill Lynch's Euro High Yield Index, the 10-year yielded just 4 basis points more than the benchmark Treasury note on Friday.

The Federal Reserve is now trying to unwind the $4.5 trillion balance sheet it stoked after the recession by gradually ceasing reinvestments of its fixed-income assets as they mature. But this won't help pop the bubble. "The real test will be when the red area in the chart below turns black," Sløk said.

And that could be negative for riskier assets like equities.

"The fear is that when the risk-free interest rate goes higher then credit spreads will widen and equities underperform as investors leave risky assets and come home to higher-yielding government bonds," Sløk added. "In finance terms, if the risk-free rate goes higher why should I then be buying risky assets?"

But the Fed will have a role to play in reducing the share of government bonds that yield negative. If inflation begins to rise in the US, Sløk said, the Fed would be inclined to raise rates faster, and that would mean higher rates in Europe and Japan.

Investors, however, aren't counting on rising inflation, judging by the magnitude of their investments in negative-yielding bonds. "The bottom line is that the central bank exit has barely started and once inflation does start to move higher then checking out from Hotel Easy Money will be a lot more difficult than checking in," Sløk said.