- In February, SpaceX launched the first private moon mission.

- Beresheet, as the 1,300-pound robot is called, was designed by the Israeli nonprofit SpaceIL.

- The four-legged spacecraft attempted a lunar landing on Thursday but crashed into the surface.

- An engine failure is suspected to be the cause of the crash.

- Visit BusinessInsider.com for more stories.

Nearly two months after its launch with a SpaceX rocket, the first private mission ever to try landing on the moon has ended in failure.

The dishwasher-size robot, called Beresheet (a biblical reference that means “in the beginning”), attempted the first private moon landing on Thursday shortly after 3 p.m. EDT. The roughly 1,300-pound four-legged probe was designed and built by an Israeli nonprofit called SpaceIL and backed by about $100 million in private funding.

Had the mission been successful, it would have made Israel the fourth nation ever to have a spacecraft survive a lunar-landing attempt.

However, its main engine failed during its descent toward the moon. By the time mission controllers rebooted the spacecraft to try and restart the engine, according to a live broadcast of the event, it was too late.

"Beresheet crashed on the surface of the moon after the main engine broke down," Eylon Levy, a journalist for i24News, tweeted after the failure.

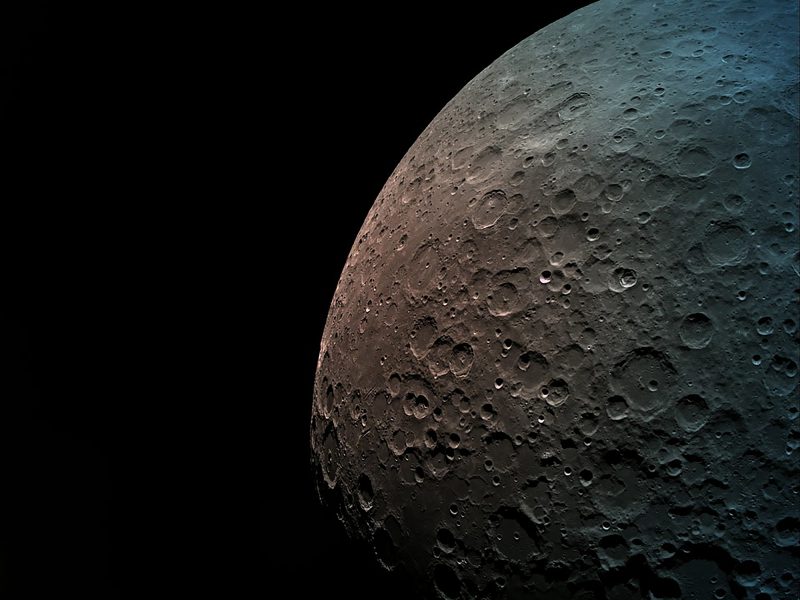

Beresheet transmitted one final photo from about 14 miles above the lunar surface, shown above, before its failure.

Thomas Zurbuchen, the associate administrator of NASA's science mission directorate, commented on the failure shortly after it occurred.

"Space is hard, but worth the risks. If we succeeded every time, there would be no reward," Zurbuchen tweeted. "It's when we keep trying that we inspire others and achieve greatness. Thank you for inspiring us @TeamSpaceIL. We're looking forward to future opportunities to explore the Moon together."

Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu, who was present at the launch following his reelection, also commented on the failure from the mission's control center in Yehud, Israel.

"If at first you don't succeed, try again," Netanyahu said.

'Kind of a weird project'

SpaceIL announced its intention to land a privately developed and funded spacecraft on the moon in 2011, during an international space conference in Israel.

The audacity of the three young engineers behind the outfit, Yariv Bash, Kfir Damari, and Yonatan Winetraub, caught the attention of a South African-born billionaire named Morris Kahn.

"They said that they were going to participate in a Google competition. It was an XPrize competition to put a spacecraft on the moon and win a $20 million prize," Kahn told Business Insider before to Beresheet's launch. "They seemed very proud of themselves, and I thought that this was rather neat."

That competition was the Google Lunar XPrize, which started in September 2007. It dangled tens of millions of dollars in prize money with the hope of spurring a private company to land a robot on the moon by 2014.

No one won the contest, but SpaceIL pressed forward with the financial assistance of Kahn, who had a net worth close to $1 billion at the time, and other donors. Kahn ended up investing $43 million toward the project's final cost of about $100 million. (The Israeli government spent about $2 million on Beresheet.)

"I don't want to be the richest man in the cemetery. I'd like to feel that I've used my money productively," Kahn said. "I'd also like to see that I've used it in a way that I enjoy. I enjoy this process."

Kahn said it was not easy to raise the money, but he appealed to the national pride of Israelis.

"Putting a spacecraft on the moon is a little bit of a kind of a weird project," Kahn said. "It almost seems un-doable, and even if it was doable, it takes somebody with imagination to actually see why you would do it."

Although the mission failed, it was relatively inexpensive compared with previous lunar-landing attempts. NASA, for example, spent about $469 million in the 1960s on seven similarly sized Surveyor lunar landers. When adjusted for inflation, that sum is roughly $3.5 billion today - about $500 million per mission.

'It just takes one little glitch'

The planned landing site for Beresheet was Mare Serenitatis, or the "Sea of Serenity," in the northern hemisphere of the moon. It's a dark lava-covered site of an ancient volcanic eruption, a source of magnetic and gravitational anomalies, and - in popular culture - the left eye of the "man in the moon."

Beresheet was designed to take measurements of the moon's magnetic field there using an instrument supplied by the University of California, Los Angeles. SpaceIL also planned to share its data with NASA and other space agencies and "hop" Beresheet to another location using its thrusters.

Read more: The American flags on the moon are disintegrating

This did not come to pass, though.

The probe was using nine engines to brake its descent toward the lunar surface: one large central main engine and eight smaller thrusters. However, the main engine briefly failed during the maneuver.

"We are resetting the spacecraft to try to enable the engine," an announcer said during a live broadcast on YouTube from mission control, later confirming the reset worked and the engine had come back online.

But it was too late: Moments later, SpaceIL lost communication with the spacecraft, indicating it had likely crashed into the lunar surface. Faces of those watching from mission control after the announcement included expressionless and despondent ones.

The mission was far from a total failure, though.

"Well, we didn't make it, but we definitely tried," Kahn said after failure during Thursday's broadcast. "I think that the achievement of getting to where we got is really tremendous. I think we can be proud."

Beresheet not only spent seven weeks in space but also closed the 239,000-mile gap between Earth and the moon, entered into lunar orbit - making Israel the seventh country ever to do so - and successfully completed a series of engine burns to poise it for a landing attempt.

Kahn told Business Insider before Beresheet's launch that there was "no guarantee" the mission would succeed. "It just takes one little glitch," he said.

Regardless of any failure, Kahn said in February, he thinks an "Apollo effect" of encouraging young Israelis to dream big about their futures in science and engineering is already a great success of the project.

"We've actually gotten to more than a million young students, and we excited them about space," Kahn said. "That objective, I think, we've actually already achieved."