By the fall of 1943, Japanese forces had been ejected from Alaska’s Aleutian Islands in the North Pacific, and the Solomon Islands in the South Pacific were on the verge of capture.

US forces now had to push into the central Pacific, from which they could target Japanese strong points and communications lines. US officials had spent much of that year preparing for Operation Galvanic: the capture of the Gilbert Islands, a group of coral atolls that are now part of Kiribati.

Held by the British until Japan seized them in December 1941, the Gilberts were “of great strategic significance because they are north and west of other islands in our possession and immediately south and east of important bases in the Carolines and Marshalls,” US Navy Fleet Adm. Ernest J. King wrote in official reports.

"The capture of the Gilberts was, therefore, a necessary part of any serious thrust at the Japanese Empire," he wrote.

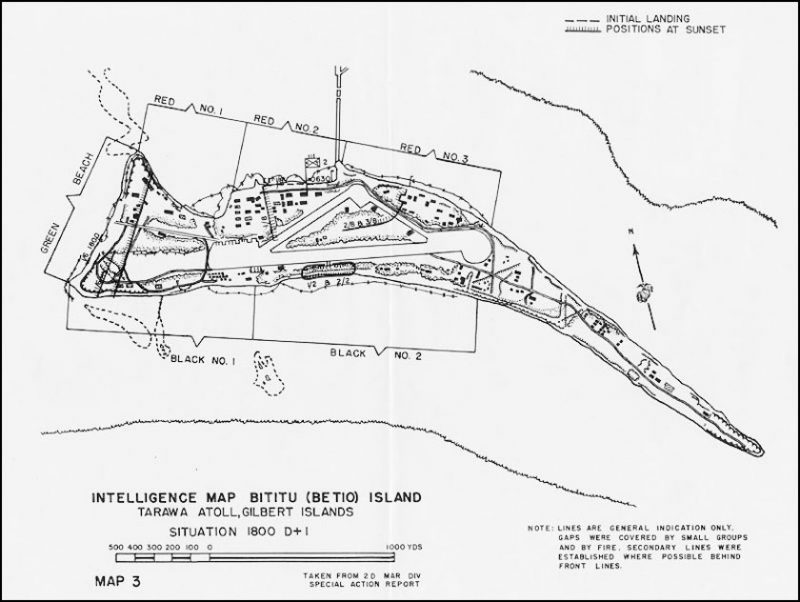

The attack on Tarawa focused on Betio, the principal island in the atoll, at its southwest corner.

"The island was the most heavily defended atoll that ever would be invaded by Allied forces in the Pacific," wrote Joseph Alexander, a historian who was a Marine amphibious officer.

US Marines stormed ashore Betio on November 20, 1943. After 76 hours of intense fighting, they had wrested it from tenacious Japanese defenders.

Here's how US Marines waded into what one combat correspondent soon after called "the toughest battle in Marine Corps history."

US planes had done reconnaissance of Betio and Tarawa since the beginning of 1943. In August 1943, Vice Adm. Raymond Spruance, commander of the US Central Pacific Force, verbally assigned the capture of the Tarawa atoll to the 2nd Marine Division. In mid-September, Navy and Army planes bombed and photographed the atoll.

Tarawa is a triangular coral atoll. Its east side is about 18 miles long, while the south side is 12 miles long and the west side 12.5 miles long. The string of islands that make up the atoll ranged in altitude from 8 to 10 feet and were covered in coconut trees and dense shrubs.

Betio is a bird-shaped island at the atoll's southwest corner that at the time had an area of about 300 acres.

Japanese commanders concentrated their forces on Betio, a strongly defended island at the southwest corner of the atoll, planning to destroy US transports at sea and then "concentrate all fires on the enemy's landing point and destroy him at the water's edge." The island was estimated to have a garrison of 4,800 men — more than half of them first-rate troops.

Betio's defenders deployed steel tetrahedrons, minefields, and dense thickets of barbed wire. Walls of logs and coral surrounded much of the island. Machine guns, rifle pits, and anti-tank ditches were often integrated into the barricades, and many emplacements, like pillboxes, were built to have converging fields of fire.

Anti-personnel and anti-vehicle mines were scattered around the island, its lagoon, and its reef. Japanese forces on the island also had naval guns, coastal-defense guns, as well as field artillery and howitzers.

Source: US Marine Corps

Betio's geography — narrow and not higher than 10 feet — suited its defenders. "Every place on the island can be covered by direct rifle and machine-gun fire," Marine Col. Merritt Edison said. The island also lacked natural cover, and its tides and reef posed unique challenges.

The fight at Tarawa was the first large-scale encounter between US Marines and Japan's Special Naval Landing Forces. Intelligence officers cautioned before the landing that "naval units of this type are usually more highly trained and have a greater tenacity and fighting spirit than the average Japanese Army unit."

Nevertheless, Marines were surprised at the intensity with which they fought.

Source: US Marine Corps

US commanders elected to attack what they believed was Betio's weakest point: its northern side, which the Japanese had yet to mine. They knew the tide was unlikely to be high enough for landing craft to float over Betio's reef but planned to use amphibious tractors to take the first wave in and then return to carry more troops.

Source: US Naval Institute, US Marine Corps

D-Day for Tarawa was set for November 20, 1943. The timetable for operations in the central Pacific left little time to gather landing craft and supplies in numbers the commanders wanted, nor for preparations, like diversionary landings on nearby islands.

Adm. Chester W. Nimitz, commander in chief of the US Pacific fleet, considered the schedule for the campaign against the Marshall Islands, eight weeks after Tarawa, inviolable. US commanders also believed the Japanese could mount an air and submarine attack with three days of the start of operations against Tarawa. These factors limited the time US forces had for planning and preliminary bombardment against Tarawa.

While en route a few days before the landing, Rear Adm. Harry Hill, commander of Task Force 53 that was to assault Tarawa, warned his force that it was "the first American assault of a strongly defended atoll" of the war in the Pacific. That was the first time the Marines learned the name of the island they were to attack.

Source: US Marine Corps, US Naval Institute

The task force's transports arrived off the atoll after midnight on November 20. US troop transports started loading their landing craft a little after 3 a.m. The plan called for a half-hour of airstrikes at 5:45 a.m. and naval fire until the landing, scheduled for 8:30 a.m. But mix-ups and schedule changes plagued US forces in the hours beforehand.

The maneuver schemes "for the landing of the assault waves at Betio Island in Tarawa Atoll brought forth the most comprehensive landing attack orders promulgated up to that date in the Pacific amphibious campaigns," according to the US Navy.

Source: US Marine Corps

The Japanese fired first, with coastal-defense guns at 5:07 a.m. US warships returned fire and then halted in expectation of strikes by US planes, but those had been postponed without warning. A second burst of Japanese fire, starting at 5:50 a.m., landed among the transports approaching Betio's shore.

Source: US Navy, US Marine Corps

"In spite of this shelling, transports completed disembarking their assault waves, and got underway to northward at 0616 ... only when enemy shells up to probably 8-inch size began getting too dangerously close," the commander of the transports reported. The Japanese salvos were inaccurate, and US warships quickly returned fire.

Source: US Navy, US Naval Institute

Disjointed shelling and bombardment continued for several hours. The landing time was delayed, first to 8:45 a.m. and then to 9 a.m. Just before 9 a.m., a Marine scout-sniper platoon and combat engineers darted onto the long pier that jutted into the lagoon, making quick work of its defenders.

Source: US Marine Corps, US Naval Institute

The scattered preliminary fire had failed to significantly damage Japanese defenses, and lulls in the firing allowed the Japanese to regain their senses and shift their forces to the landing beaches. US transports and landing craft were hindered by strong tides and headwinds.

Source: US Naval Institute, US Navy

Marine assault waves were met with steadily increasing enemy fire. The amphibious tractors that took the Marines ashore had trouble with the seawall, leaving them stuck on the beach and vulnerable to pre-sighted Japanese fire.

The island's defenders' hand grenades were lethal. Cpl. John Spillane, a St. Louis Cardinals prospect before the war, caught two grenades barehanded and threw them back before a third exploded in his hand.

Source: US Marine Corps

The tractors fared well during the initial assault — only eight were lost to enemy fire. But they were gradually knocked out while in transit or ran out of fuel. The second and third waves of landing craft didn't have as much armor, and Japanese fire was especially damaging to them.

Source: US Marine Corps

Other landing craft couldn't make it over the island's reef, and many Marines had to wade ashore through withering Japanese fire. Some Navy coxswains ordered Marines off seaward of the reef into deep water in which many drowned. Some companies sustained 70% casualties while approaching the beach.

"Those who were not hit would always remember how the machine gun bullets hissed into the water, inches to the right, inches to the left," Robert Sherrod, a correspondent for Time, wrote of landing.

Communication was also increasingly difficult, as water damage and enemy fire had knocked out radios. There was either silence or chaos on command networks, and no one on the force's flagship knew what was happening on the beaches. Many troops, already embarked, would not make it ashore until sunset or the next day.

Source: US Marine Corps, US Naval Institute

Landing forces continued to struggle ashore Betio. Once joint Navy-Marine shore-fire-control teams landed, however, fire support improved considerably. One team called down fire on a group of Japanese soldiers crowded around a bunker, killing the commander of the island's garrison and his staff. The Marines' artillery was operational by daybreak on the second day.

Source: US Naval Institute, US Marine Corps

At the end of the first day, 5,000 men had crossed Betio's reef, but 1,500 of them had fallen or were missing. US lines were thin and vulnerable — many Marines had struggled to get over the seawall on the beach. The fire coming over the coconut-tree logs was so heavy "a man could lift his hand and get it shot off."

Source: US Naval Institute, US Marine Corps

While the Japanese commander's plan called for swift counterattacks, his death during the day, as well as damage to Japanese communications, left his lieutenants on their own. They would not launch a major counterattack until the third night.

Source: US Navy, US Naval Institute

Horrific US losses continued on November 21. A communications failure put reserve troops ashore in the face of strong Japanese fire, and they took heavy losses. "This is worse, far worse than it was yesterday," Sherrod wrote, counting hundreds of casualties.

Source: US Marine Corps

But within hours, Marines — supported by surviving Sherman tanks — had cleared Green Beach on the west side of the island. That success allowed an entire battalion of Marines to land with all their weapons. Fighting remained intense and communications faulty during the second day, but Marine officers could bring some order to the chaos.

Source: US Marine Corps

The battle began to turn decisively in the US's favor around midafternoon on November 21. Supplies came ashore, Marine artillery added close fire support, and Marines moved out of their beachheads, despite heavy Japanese fire. More Marines came ashore during the afternoon and evening of the second day.

Source: US Marine Corps

The third day began with concerted US attacks against Japanese positions around the island. The US made significant gains, but progress was slow, and Japanese resistance remained fierce. There were heavy casualties among Japanese and US officers, hindering each side's operations.

Source: US Marine Corps

The third night saw the remaining Japanese forces counterattack. They scouted US troop and weapons locations then launched themselves at US positions in several waves throughout the night and early morning. Marines, supported by artillery and naval fire, fought them off after hours of close-quarters combat. The counterattack broke the Japanese defense, as nearly 600 Japanese died in the open during the night.

Source: US Naval Institute, US Marine Corps

By November 23, 1943, after 76 hours of fighting, the battle for Betio was over. More than 1,000 Marines and sailors had been killed, and nearly 2,300 were wounded. Of the roughly 4,800 Japanese defenders, about 97% were thought to have been killed. Only 146 prisoners were captured — all but 17 of them Korean laborers. More casualties would come in operations on surrounding islands.

The intense bloodshed on Tarawa, documented by war correspondents who were close to the fighting, sparked outcry in the US. Many criticized the strategy and tactics at Tarawa, but the Navy and Marine Corps drew lessons from the battle and applied them throughout the war, and Betio's airfield supported operations against other vital positions in the Pacific.

"The capture of Tarawa knocked down the front door to the Japanese defenses in the Central Pacific," said Nimitz, the commander in chief of the Pacific fleet.

Source: US Marine Corps

The island was steeped in carnage. "Betio would be more habitable if the Marines could leave for a few days and send a million buzzards in," Sherrod wrote after the fighting. US forces moved on to other islands in the atoll, encountering tenacious Japanese defenders. But on November 28, Marine Gen. Julian Smith, commander of the 2nd Marine Division, declared the enemy on Tarawa "wiped out."

Source: US Naval Institute, US Marine Corps

Rear Adm. Harry Hill, who commanded the task force attacking Tarawa, called Betio "a little Gibraltar" and said that "only the Marines could have made such a landing." Four Marines were awarded the Medal of Honor for their actions during the battle — three of them posthumously.

A memorial on Betio, erected by the New Zealand government, is dedicated to the US Marines and Navy personnel who fought there.

Source: US Marine Corps, US Army Center for Military History