Jesse Pratt López

- One of Georgia’s largest counties has become only the second in the state to offer election materials in Spanish, and the first to do so in Korean, potentially making it easier for thousands of voters to cast ballots on Tuesday.

- With the move, Dekalb draws a contrast to Gwinnett County, which only translated materials into Spanish when the federal government told them to.

- Both counties are using election materials in a language other than English for the first time in a presidential election.

- Visit Business Insider’s homepage for more stories.

One of Georgia’s largest counties has become only the second in the state to offer election materials in Spanish, and the first to do so in Korean, potentially making it easier for thousands of voters to cast ballots on Tuesday.

The announcement came Thursday, as Georgia eclipsed 3.6 million early votes (in person and mail) – 70% higher turnout than 2016 – and with the state in play for Democratic candidates from former Vice President Joseph R. Biden on down the ballot.

The effort was a “landmark decision,” said Dekalb County Commissioner Larry Johnson, who urged the county to take the initiative of translating sample ballots, frequently-asked questions, and drop-box locations – drawing a sharp contrast with Gwinnett county, which only began providing election materials in Spanish in early 2017 after the federal government notified officials of their obligation to do so.

With Dekalb’s decision, the state’s second- and third-largest counties are making voting in a presidential election possible in languages other than English for the first time — and Georgia’s changing demographics, already under the spotlight, assume a higher profile. About 15% of Dekalb’s 759,297 residents speak Spanish or Korean, Johnson said; nearly 22% of Gwinnett’s 936,250 residents are Hispanic.

“It was a no-brainer,” Johnson said, noting that his county had received a private grant in recent weeks to expand voting access, around the same time a nonprofit organization approached him with suggestions of certified professionals who could help translate election materials into Spanish and Korean, which are also the second and third most widely spoken languages in Georgia, respectively.

The approach differs greatly from Gwinnett County's, which for years not only said "'no', but 'hell no,'" to translating election materials as said by Jerry Gonzalez, executive director of the Georgia Association of Latino Elected Officials. His and other organizations had been pushing the county to provide election materials in Spanish since the mid-2000s, as the county's population shot upward, driven by Latinos.

"There was a lot of resistance" to making the move, Gonzalez said. But 2015 Census figures showed that Gwinnett fell under Sec. 203 of the Voting Rights Act, which requires jurisdictions to provide bilingual election materials if more than 5% or 10,000 citizens of voting age are members of a single language minority and have difficulty speaking English.

By contrast, officials in "Dekalb weren't waiting [to reach the threshold], and are leading from the front," said Nse Ufot, CEO of the New Georgia Project, a nonpartisan group that works on voter registration and engagement, in a press conference announcing the initiative. "It's a blueprint for other counties across Georgia, and across the South."

Commissioner Johnson said he was not aware of the importance of language access in voting, as his district is mostly English-speaking and African-American. But when Asian Americans Advancing Justice - Atlanta, an advocacy group, approached him about the issue, he thought, "I can identify with and understand how barriers to voting can affect certain populations."

Jesse Pratt López

"I view the lack of language access as voter suppression," said Stephanie Cho, executive director of the organization. "You see local schools and government agencies with information in multiple languages, but voting is an English-language-only playground."

Cho said Dekalb followed the "best practice" by paying professional translators and having her organization review translations. According to the federal government, "[l]ocal officials should reach out to the local minority community to help produce or check translations" when translating materials in compliance with Section 203.

Gwinnett appears to have taken a different approach. "Even after they were mandated [to translate], they did not reach out," Gonzalez said. It's unclear if they reached out to other local organizations. His organization and others flagged materials in 2017 that "sounded weird" in Spanish but haven't revisited the issue since. A quick look at some of Gwinnett's Spanish-language materials in the current election drew laughter, and surprise, from Nicolás Arízaga an American Translators Association member who specializes in political and legal translations.

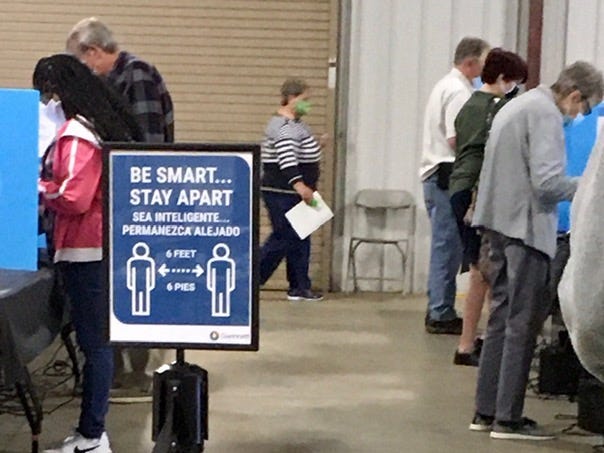

One example: a sign in every polling place which tells voters to "Be Smart, Stay Apart," with arrows separating two human figures at a distance of six feet. The Spanish version: "Permanezca alejado." Arízaga's response: "'Keep yourself apart'? From where? From what?" Also, the "feet" in the sign were translated literally – even though Spanish-speaking countries use the metric system, he noted.

Timothy Pratt

The translator's attention was also drawn to a mailer Gwinnett sent out informing voters about how to prepare an absentee mail-in ballot, a subject of particular importance in this election. The problem: "absentee mail-in ballot" was translated literally, word for word: "Voto ausente por correo." "What does that mean?" replied Arízaga, laughing again. "In Spanish, it doesn't mean anything!" The problem lay not only in the translation itself but also in not acknowledging that "most Latinos are not familiar with this," he added of absentee voting.

After reviewing other examples, including a referendum on the county's ballots, the translator surmised, "It's Google translate — or a literal translation … I don't see how you can say you're caring about voters and their votes, but not care enough not to use Google! … You don't care enough to communicate well!" He also noted that the county's printed materials directed voters to its website, but the website didn't have a button or other means for directing them to information in Spanish.

Gwinnett County did not respond to several requests for comment.

Commissioner Johnson said obtaining a grant and guidance from community organizations around the same time made Dekalb's effort easier. "All things happened synergistically to allow us to do it," he said. At the same time, "If I'd have known about this [issue] earlier, we'd have done it earlier," he added.

Johnson wears another hat: first vice president of the National Association of Counties, an organization representing more than 3,000 county governments. In this capacity, he hopes to spread the idea of expanded language access at the polls. At the press conference announcing Dekalb's effort, a Korean woman named Soon Hyung Heo spoke about how she had voted for many years, but with a "heaviness in my heart," because she was unsure of certain choices she made. "That's when it came to me," Johnson said. "We're gonna help generations. We're gonna bring people together who were invisible — so now they can fully participate in the democratic process."