- The US Food and Drug Administration barely regulates the cosmetics industry: just 11 ingredients are forbidden in cosmetic products in the US. In Europe, more than 1,300 compounds are barred.

- The retail chain Claire’s has come under fire – first in March and then again last week – after asbestos, a known cancer causer, was found in eye shadow and foundation sold there.

- Experts say this is part a larger issue: The US beauty industry is not subject to many rules, and some of the ingredients in makeup could make people sick.

- Visit Business Insider’s homepage for more stories.

Dr. Shruthi Mahalingaiah used to love shopping at Sephora. She bought so much makeup, she said, that she’d get “little random gifts” with her purchases.

“I had drawers full of makeup, all sorts of makeup,” Mahalingaiah told Business Insider.

But she no longer sets foot in the store. After she started studying the health effects of chemicals in cosmetics, Mahalingaiah – a gynecologist at Boston Medical Center – paired her beauty routine way down.

“Cosmetic molecules used in the shine or luminescence are often derivatives of PFAS and PFOAs,” Mahalingaiah said.

These chemicals are endocrine disruptors, which means they can subtly change how our bodies work by shifting the way our hormones operate. Such hormone disruptors have been linked to metabolism issues, low sperm counts in men, and early menopause in women. They can also do long-term damage to a developing fetus, subtly reducing a baby's brain power and upping the odds of a premature birth.

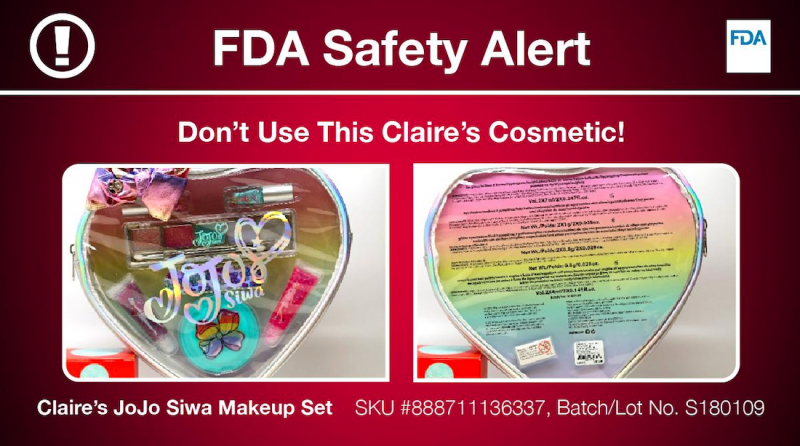

PFAS chemicals are not the only problematic ingredients in makeup: Asbestos, a known cancer-causer, was recently found in the JoJo Siwa makeup kit for kids, which is sold at Claire's, according the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA). That kit includes eye shadow, nail polish, and lip gloss. Asbestos was also found in the Beauty Plus Global Contour Effects Palette, the FDA said.

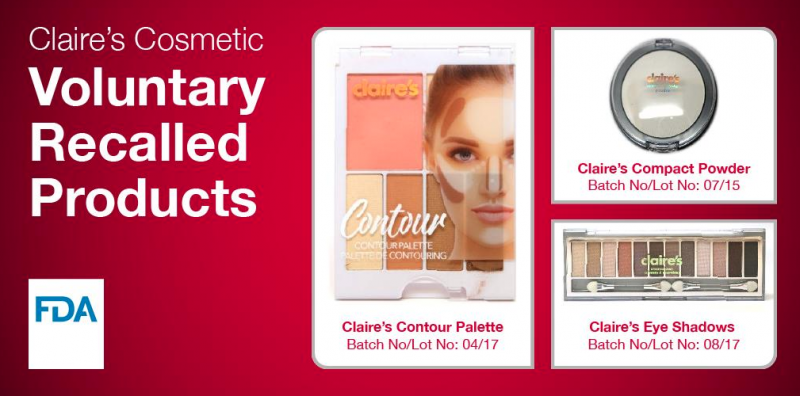

This recent asbestos discovery comes after the toxin was also found in Claire's brand eye shadows and face powder in March.

"It wasn't surprising to me, because there's no regulation," Mahalingaiah said at the time.

The FDA is warning consumers not to use any of the products that tested positive for asbestos, but the agency has also pointed out in the past that it "does not have authority to mandate a recall." (Instead, Claire's issued a voluntary recall for the company's own products in March.)

Leo Trasande, a public-health expert from NYU's Langone Health network, thinks the FDA could do more to test for dangerous compounds in makeup and communicate the health risks of cosmetics to the public.

"This is quite late in the game for FDA to rush out and insist that this is a problem," Trasande, who recently wrote a book on endocrine-disrupting chemicals, previously told Business Insider. "They've known that this is a problem for some time. There is no level of asbestos that is safe."

The US has not enacted new cosmetics regulations in over 80 years

The US law that regulates cosmetics - the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act - hasn't changed since it was enacted in 1938. While Europe has banned over 1,300 chemicals from products sold there, the US forbids just 11. Congress wrote drafts of new cosmetic rules in 2011 and 2018, but neither was enacted.

"Cosmetics have largely fallen into a regulatory black hole," Scott Faber, the senior vice president of government affairs at the Environmental Working Group, said in testimony before the House Subcommittee on Economic and Consumer Policy in March. "Cosmetics manufacturers do not have to register with FDA, do not have to report ingredients, do not have to report adverse events."

This is different from how the FDA treats drugs, medical devices, and food.

The lack of regulation means manufacturers of makeup, shampoo, lotion, and other personal-care products in the US can put almost anything they want into those items, including compounds known to raise cancer risk, like coal tar, formaldehyde, and lead.

To make matters murkier, producers are permitted to label their products with ingredients like "fragrance" or "parfum" instead of disclosing the specific chemicals that make up those elements of a product (since those formulations are considered trade secrets). So fragranced beauty products could easily contain a toxic compound without consumers ever knowing.

Sens. Dianne Feinstein and Susan Collins are pushing for a new Personal Care Products Safety Act, which would require the FDA to evaluate the safety of at least five new ingredients used in personal care products each year. The policy would also give the FDA authority to issue recalls for harmful beauty products consumers put on their lips, eyes, and bodies.

Sen. Debbie Dingell is also sponsoring legislation to address the asbestos issue; it would require products marketed to kids to either be deemed safe and asbestos-free or carry a warning.

"Asbestos in children's cosmetics is simply unacceptable," Dingell said in a release. "It is so basic we shouldn't need legislation to ban it, but we do."

How much of a toxin is too much?

Because cosmetics are designed to make people attractive to others, they often mimic one of nature's best-known phenomena: the glow women get when pregnant.

"Thick eyelashes, thick eyebrows, flushed cheeks, big lips, all of this happens under the effects of estrogen," Mahalingaiah said, adding, "it might be the effect a person putting on the makeup might want, but through a pathway that's maybe not the healthiest."

Scientists know that exposure to asbestos raises a person's cancer risk, but the effects of the hormone-disrupting chemicals that can be found in makeup aren't as clear. Researchers are still trying to figure out, for example, how compounds in anti-aging products bind to the estrogen receptors in our bodies.

There are signs, however, that women who use more cosmetics may see health consequences like early menopause, more hot flashes, painful cases of endometriosis, and long-term damage to their DNA, which can lead to cancer.

"Why do we always need to look fertile and pregnant?" Mahalingaiah asked.

Research on endocrine disruptors also suggests that the chemicals may subtly slow down people's metabolisms and contribute to chronic health issues like obesity and infertility, even in small doses. This is true for people of all ages and sexes, as well as developing fetuses.

Take phthalates, for example: the ingredients that keep products like shampoo fresh.

"Phthalates disrupt the function of the male sex hormone," Mahalingaiah said.

Studies show that men exposed to high concentrations of those chemicals in the womb can have lower testicular volume, less semen, and lower semen quality than other men.

The best solution may be to use fewer products

Mahalingaiah said she recently performed an at-home urine test on herself, and found elevated concentrations of parabens (one of the most common estrogen-influencing ingredients in beauty products) in her body. She also found the sunscreen ingredient benzophenone-3 (BP-3), which can mess with the way hormones typically function.

To the dismay of her three young daughters, Mahalingaiah said she threw away her 100-shade eyeshadow palettes, since PFAS chemicals are often used to make those cosmetics shimmer.

Mahalingaiah now recommends that any step in one's beauty routine that isn't obviously beneficial to their health (like putting on sunscreen) should probably be re-examined.

"My piece of advice would be thinking about why [people] think they need a lot of makeup," she said. "People are using makeup primers, and then base coats, and then these other coats, and then the spray that locks it all in."

Each additional product a person uses could raise the risk that their endocrine system gets disrupted, she said. Even so-called "natural" beauty products, which purport to have fewer fragrances and plasticizers, can still masquerade as a healthier alternative with largely the same ingredients.

"How much science do you need, when there are known carcinogens or toxicants, to make a choice to reduce exposure?" Mahalingaiah asked. "How much data do you need?"

Still, she admits that she falls for the shimmering, radiant formulations chemists come up with on occasion.

"I haven't thrown everything out," Mahalingaiah said. "I just reduce the frequency of use."

Trasande suggests consumers vet their own personal-care products through a database like EWG's Skin Deep.

Once you stop using endocrine-disrupting chemicals, studies suggest the concentrations of them in your body can diminish quickly. A 2016 study of 100 14- to 18-year-old girls showed that when they stopped using products with ingredients like phthalates, parabens, triclosan, and BP-3, their urine concentrations of those chemicals dropped 27-45% in just three days.

Mahalingaiah said consumers should think about how to reduce their exposure: "What do you really need? Can you do with less?" she asked.

Buying fewer products, of course, would also save you cash.

Update: This story was originally published on March 12, 2019. It has been updated with the latest makeup recall news.

- Read more:

- 32 of the most dangerous things science has strongly linked to cancer

- A toxic-chemicals expert is sounding the alarm about 4 cancer-linked chemicals that could be making us sicker and fatter

- A Yale skin cancer expert says the popular notion that you need to soak up Vitamin D from the sun is a myth

- Johnson & Johnson is being investigated by the SEC over fears its baby powder may cause cancer - here's how worried you should be