Gail Johnson/Getty Images

- A new study offers insight into why Stonehenge has remained unchanged since it was built 5,000 years ago.

- Sarsens, the massive boulders that make up part of Stonehenge, contain interlocking quartz crystals.

- Those crystals – some of which are 1 to 1.6 billion years old – make the rock very durable.

- See more stories on Insider's business page.

Much of Stonehenge has remained almost unchanged since Stone Age builders erected its massive sandstone boulders, or sarsens, 5,000 years ago on England's Salisbury Plain.

A new study reveals how the monument has stood the test of time so successfully: The quartz crystals that make up the sarsens form an interlocking structure that makes the boulders nearly indestructible.

"Now we've got a good idea why this stuff's still standing there," David Nash, a professor of physical geography at the University of Brighton who co-authored the study, told Insider. "The stone is incredibly durable – it's really resistant to erosion and weathering."

The study also revealed that some of Stonehenge's sarsens contain grains of rock that are between 1 billion and 1.6 billion years old.

Unlocking the sarsens' chemical secrets

Lewis Phillips

The new research was born out of an act of repatriation.

In 1958, a team was repairing a cracked chunk of sandstone, and a driller named Robert Phillips took a 3-foot-long piece of Stonehenge. He eventually brought the relic to his home in Florida, but after 60 years, the Phillips family repatriated it to Historic England, a charity that preserves Stonehenge.

The rock's return offered Nash's team an opportunity to investigate the monument's geological origins. Stonehenge is protected by law, so it's impossible to extract new samples for study.

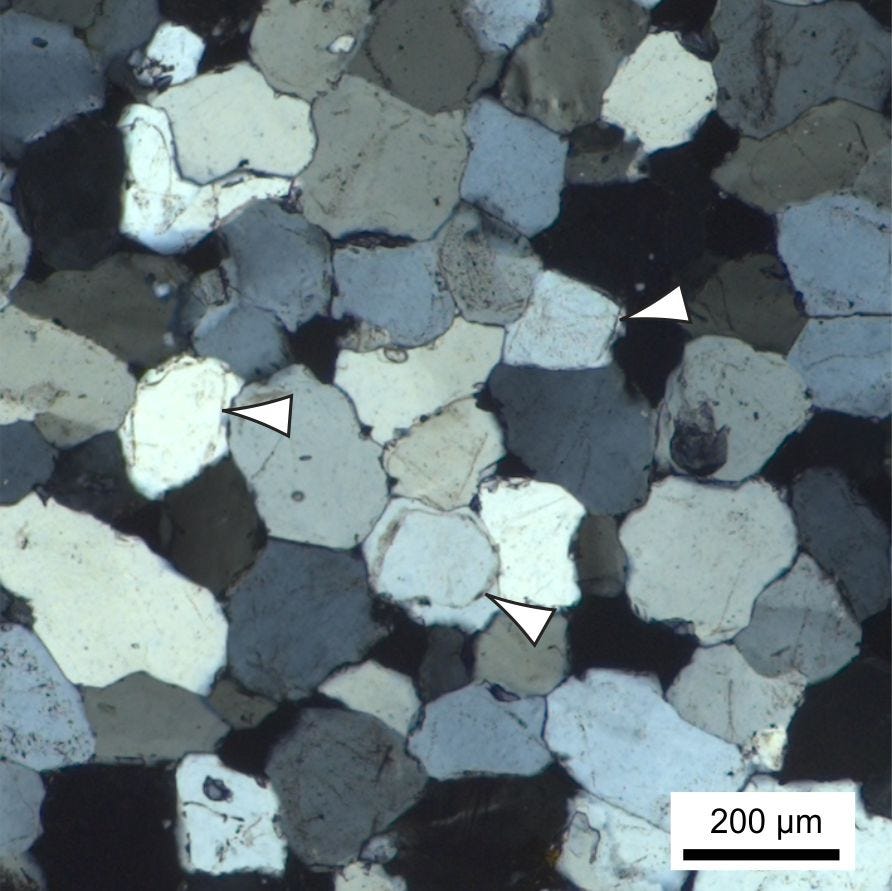

The researchers analyzed Phillips' sample, along with another found in a nearby museum, to look at the sarsens' inner structure. They zapped the rock with X-rays, looked at it under microscopes, and CT-scanned it.

"This small sample is probably the most analyzed piece of stone other than moon rock!" Nash said in a press release.

His team discovered that the sample contains tiny grains of quartz that fit together like a puzzle. These grains were cemented together by other quartz pieces that crystallized - "creating this incredibly strong interlocking matrix of crystals that make up the rock," Nash said.

Trustees of the Natural History Museum

That interlocked structure could help explain why Stonehenge has persisted for millennia.

The research also revealed that the sarsens are composed of sediment deposited during the Mesozoic era, between 252 million and 66 million years ago, when dinosaurs walked the Earth.

The piece Phillips took came from a sarsen called Stone 58 - a boulder sticking 21 feet out of the ground, and weighing about 24 tons. Stonehenge originally had 80 such sarsens in square-shaped archways, but only 52 remain. According to Nash, 50 of those 52 share the same chemical makeup, so it's likely the findings from Stone 58 apply to the rest.

"Nobody's looked at a sarsen in such detail before, it's a nice little illustration of Stonehenge's history," he said.

Sam Frost (English Heritage)

The sarsens likely came from nearby woods

Neolithic people erected Stonehenge in two waves of construction 5,000 and 4,500 years ago. The monument consists of two concentric circles of sarsens, with smaller bluestones set up between those arcs.

Archaeologists traced the bluestones to a site called Waun Mawn in Wales, 140 miles away. Some evidence suggests the bluestone circle was built there first, then moved to its final resting place centuries later. When Stone Age farmers migrated east across the island, they brought the bluestones, weighing 2 to 4 tons, with them.

But the sarsens' origin remained a mystery until last year, when Nash helped discover that the sandstone boulders came from an area 15 miles away from the monument called West Woods.

Katy Whitaker/Historic England/University of Reading

Nash thinks Stonehenge's builders likely used some sort of roller, or dragged the sarsens on a slippery surface like frosty ground.

"There's no evidence they used animals to do it, but we don't know," he said.

Stonehenge's builders 'picked the right stuff'

Ideas about what Stonehenge was used for run the gamut from a celestial calendar to a sacred graveyard. The monument's main entrance aligns with sunrise on the summer solstice.

"Put simply, Stonehenge was the ceremonial center of southern England," Matt Leivers, an archaeologist with Wessex Archaeology in England, previously told Insider.

James Davies/English Heritage

Nash said he isn't sure whether Stonehenge's builders knew "they picked the right stuff to build a monument that's going to last a long time."

But had they picked a different type of local material, like the chalk rock that makes up England's White Cliffs of Dover, Stonehenge wouldn't have remained standing this long.

Any threat to the monument's longevity now, it seems, would come from local bunnies.

"The only thing that could happen with Stonehenge is potentially rabbits might burrow under the stones and undermine them from below, making them fall over onto their sides," Nash said.