- Ice melting rates in Antarctica tripled between 2012 and 2017, according to a study published in the journal Nature.

- The biggest increase has been ice melt in West Antarctica, where glaciers and ice sheets are vulnerable to warmer ocean temperatures.

- Experts think that if we don’t get climate change under control quickly, ice sheets in West Antarctica could collapse, leading to rapid sea level rise around the globe.

In the future, seas will rise far higher than they are today. The question is whether it happens quickly or slowly.

There’s enough ice stacked on top of Antarctica to raise seas around the globe by almost 200 feet. While it takes time for major changes to occur with that much ice, Antarctica is melting faster than we thought, according to a study recently published in the journal Nature.

The melting rate has been speeding up significantly in recent years.

Between 1992 and 2017, Antarctica lost more than 3.3 trillion tons of ice, causing sea levels around the globe to rise an average of 8 millimeters. About 40% of that loss occurred between 2012 and 2017, according to the new study. From 1992 to 2012, the continent lost about 84 billion tons of ice a year, and over the next five years, that jumped to more than 240 billion tons per year.

If the acceleration of ice melt were to continue, it could potentially cascade, leading to runaway ice melt and rapid sea level rise.

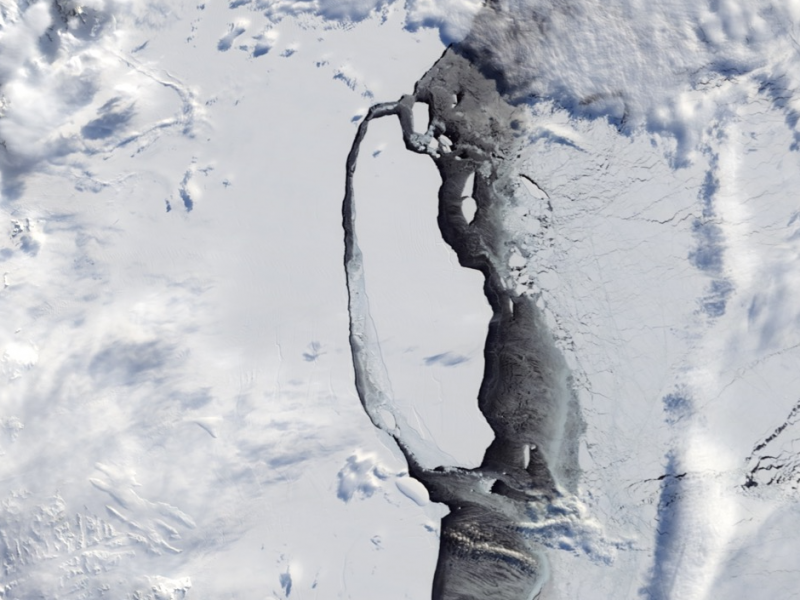

The biggest changes have come in West Antarctica, where the glaciers holding back ice sheets rest on rapidly warming ocean waters, causing them to melt more quickly.

Climate science professor Chis Rapley of the University College London has previously described Antarctica as a "slumbering giant" of ice melt and sea level rise that seems to be awakening.

"This paper suggests it is stretching its limbs," he told the UK Science Media Center.

Melting ice, rising seas

For the new study, scientists from 44 international organizations combined data from 24 different satellite surveys.

"Thanks to the satellites our space agencies have launched, we can now track [polar ice sheet] ice losses and global sea level contribution with confidence," said Andrew Shepherd of the University of Leeds, who led the study along with Erik Ivins of NASA's JPL Laboratory. "[T]he continent is causing sea levels to rise faster today than at any time in the past 25 years."

Their research brings our understanding of the current state of Antarctic ice up to date, according to researchers not involved in the study.

While 8 millimeters of sea level rise from Antarctic melting alone might not sound extreme, the rapid changes associated with it should be enough to give anyone pause.

In the 20th century, sea levels around the globe rose about six inches on average, Michael Oppenheimer, a professor of geosciences at Princeton, said during a recent media briefing on sea level rise. That was enough to narrow the typical East Coast beach by about 50 feet.

Since the mid-1990s, places like Miami have seen an additional five inches of sea level rise. Seas rise faster in some places than others, due to ocean currents and the effects of gravity.

The loss of ice on one side of the world tends to make seas rise on the other side, due to gravity. As mass from the Antarctic ice sheet is lost, gravity in that region decreases, which means that places furthest from that ice sheet tend to see the biggest increases in sea level.

Right now, three factors contribute about equally to global sea level rise, according to Oppenheimer. First, as the world has warmed as result of the burning of fossil fuels, oceans have absorbed the majority of the heat. Warmer water expands, which takes up more space. Second, glaciers are melting, adding more water to the system. The third factor is the ice sheets in Antarctica and Greenland that are still protected by glaciers.

But if or when glaciers holding those ice sheets back collapse, ice sheets are expected to become by far the biggest cause of sea level rise. And one of the most vulnerable ice sheets is that one on West Antarctica, where the melting rate has increased most quickly.

Time is running out

In an article published alongside the new research, a team of researchers described two possible scenarios for the near future.

Within a short period of time, we'll have either taken action to drastically reduce greenhouse gas emissions and climate change, or we won't.

If we dramatically cut emissions and keep global temperature from climbing more than two degrees Celsius by the end of the century, we're far more likely to avoid rapid ice sheet collapse, according to the authors.

We've already baked a certain amount of sea level rise into the planet's system. Global temperatures are close to what they were about 125,000 years ago, when seas were 20 to 30 feet higher than they are now, according to Andrea Dutton, a geologist at the University of Florida who spoke at the same sea level rise briefing. That means the planet will see at least that much sea level rise eventually, though if we're lucky it'll take hundreds or thousands of years to get there.

But the scenario where we don't cut emissions, if we don't do anything about climate change, is a lot more disturbing. In that case, the authors of the new article in Nature argue that by 2070, we could start to see the rapid loss of ice sheets.

If the glaciers holding back ice sheets in Greenland and Antarctica were to collapse, massive quantities of ice could pour into the world's oceans, leading to rapid sea level rise - something known as a "pulse."

If such a scenario were to occur, current sea-level rise predictions for vulnerable cities like Miami would be far too low. In the case of a pulse, some experts think coastal cities could see more than 10 feet of sea-level rise by 2100.

"If we aren't already alert to the dangers posed by climate change, this should be an enormous wake-up call," Martin Siegert, co-director of the Grantham Institute at Imperial College London, said to the Science Media Center.