I recently tracked down and read William Bolitho’s “Twelve Against the Gods,” an out-of-print, one-time bestseller from 1929 that’s become scarce in the wake of an endorsement from Tesla and SpaceX CEO Elon Musk.

The book spotlights a dirty dozen of historical characters who rebelled against convention in some form (with occasionally disastrous results). Bolitho’s renderings of this rogue’s gallery of figures is historically problematic in parts, but it still makes for an interesting read – one that reveals quite a lot about the author’s ideas about success and greatness.

The best chapter shone the spotlight on a young patrician from ancient Rome named Lucius Sergius Catilina – commonly called Catiline. In his typical exuberant fashion, Bolitho dubs Catiline “one of the most interesting possibilities in the history of the world.”

The author kicks off the character sketch with some notes on background (describing Rome as a gilded, corrupt city and comparing its trajectory to that of the US – according to Bolitho, by 2029, we’ll very closely resemble the ancient empire). He calls Catiline a figure that could arise in any century – a patrician on the verge of being ousted from Rome’s elite due to financial ruin.

Catiline also had more than a few skeletons in his closet, which is impressive, considering this was a time before closets were even invented. He’d messed up his tenure as governor of Africa (the Roman province, not the entire continent); allegedly murdered his brother-in-law; viciously persecuted rivals during a coup; and seduced a Vestal Virgin who just happened to be the sister-in-law of the consul Marcus Tullius Cicero … spoiler alert: He’s going to come up again later.

At a certain point, drowning in debt and reeling from his mess of a life, Catiline began plotting a "blood of night and fire" to kill Cicero, take over Rome, and abolish all debt. Bolitho characterizes the scheme as "... a sinister drollery, the simple delight of stirring up great crowds to die and kill."

However, crushing, insurmountable debt was a huge issue for many Romans. Whatever his motives (ulterior, pure, or otherwise), Catiline's cause proved popular amongst poor people and veterans in particular.

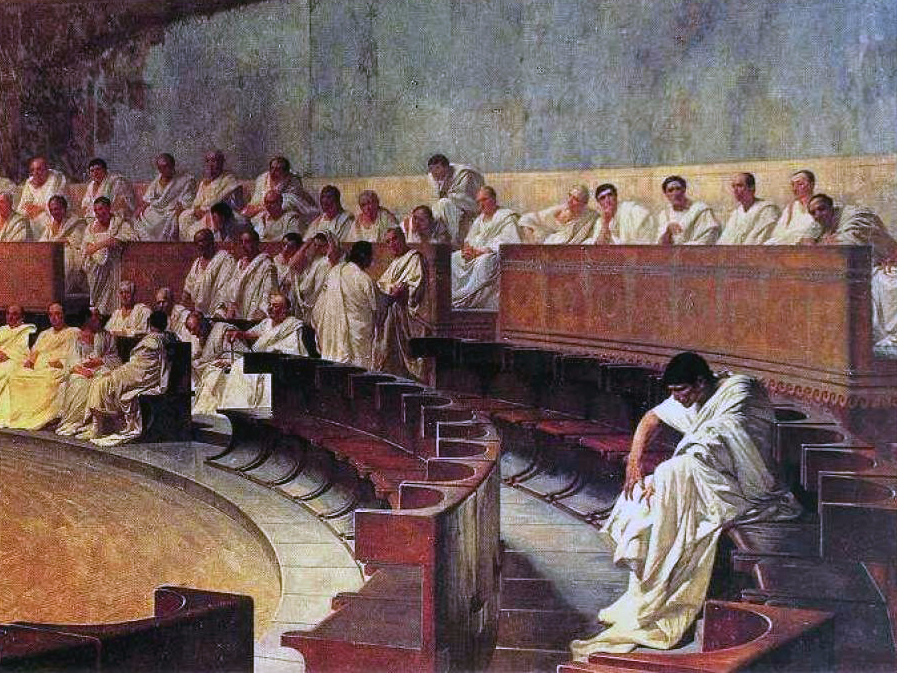

The plan crumbled when a patrician woman named Fulvia became aware of the plot and warned Cicero of his impending assassination. After rounding up a number of conspirators, Cicero showed up at the Senate and was surprised to find Catiline there, too.

Cicero proceeded to deliver a "pitiless and unwavering" speech denouncing Catiline and the conspiracy. It got so scathing that all of the other senators began sliding away from Catiline, until he was all alone on one side of the room. Exposed, the conspirator fled Rome and led a hasty battle against the Republic's forces. Catiline died in the fighting and the conspiracy was squashed.

Bolitho describes the young Roman aristocrat's adventure as "one of the most surprising of all," as he did not have much to gain considering the unlikelihood of the plot's success. This chapter provides an interesting counterpoint to some of the more positive, jovial depictions of adventurers elsewhere in the book.

Catiline loathed the Roman system and promised change, but lacked the temperament, planning skills, and ability to carry out his idea. Once the plot was unveiled, he rushed into a hopeless battle and only succeeded at getting himself and many of his followers slaughtered.

Regardless of his true motives, Catiline represents the darker side of adventuring and innovation. Fresh, new ideas can go very wrong and execution can be more important than ideas themselves.