- Ancient Egyptians worshipped and mummified animals, but examining those animal mummies without damaging the corpses is challenging for archaeologists.

- In a new study, scientists reveal a new way to peer inside delicate mummies using a type of x-ray.

- They x-rayed three mummies: a cat, a cobra, and a kestrel. The imaging technique allowed the researchers to learn about how these animals lived, died, and were mummified.

- Visit Business Insider’s homepage for more stories.

Ancient Egyptians mummified and buried millions of animals, often treating creatures like cobras, cats, and crocodiles with the same reverence and respect that they gave to a human corpses.

That’s because the Egyptians believed animals were reincarnations of gods. So mummifying them and worshipping these animals in sacred temples was a way to honor these deities, and mummified animals could also serve as offerings to those gods.

But for archaeologists, studying animal mummies without damaging them is challenging. Unwrapping a mummy to get a closer look can destroy the ancient corpse, leading to the loss of critical information about how the animal was killed or preserved.

But a study published Thursday in the journal Scientific Reports reveals a new technique scientists can use to peer under the delicate wrappings without removing them. By using micro-CT scanning – imaging that relies on X-rays to see inside an object – researchers were able to identify the species and manner of mummification for three specimens: a cat, a snake, and a bird.

"Micro-CT's high resolution can tell us more about an animal mummy: What conditions it was kept and cared for in life and how it died," Rich Johnston, the lead author of the study, told Business Insider.

When reading the scans, he added, "you're the first person in thousands of years to see what's inside."

Here's what Johnston's team found out about the animal mummies.

Ancient Egyptians mummified as many as 70 million animals, according to the study authors.

They mummified birds, crocodiles, cats, snakes, and even lions and lion cubs.

Typically, such animals were bred or captured by keepers, then killed and embalmed by temple priests. The creatures' organs were removed and their bodies dried out and wrapped in linens.

Johnston chose three such mummies from the collection held by the Egypt Center at Swansea University in the UK. Each is more than 2,000 years old.

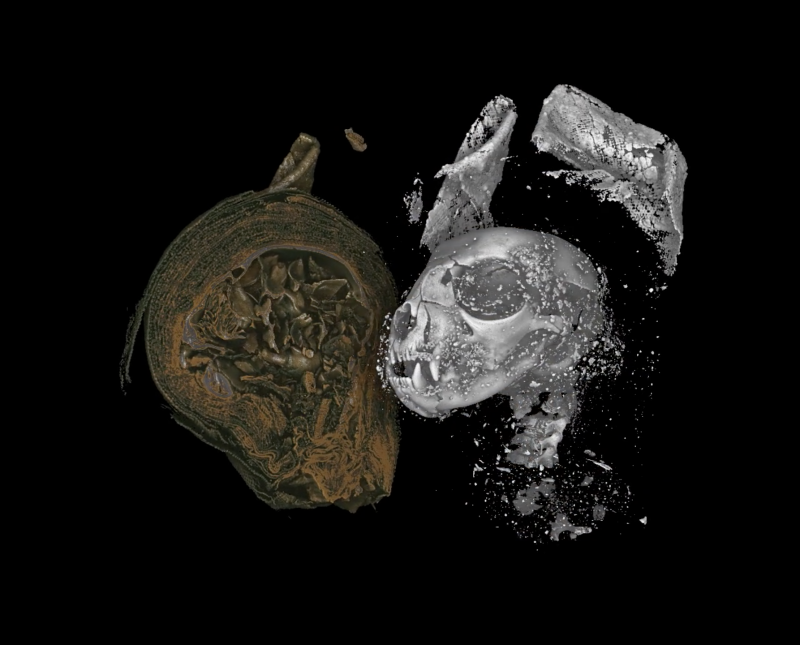

The first was a coiled snake "wrapped like an oval package," Johnston said.

Using the new imaging technique, Johnston's team identified the mummy as a juvenile Egyptian cobra. They found evidence that the snake's kidneys were damaged, indicating it was probably deprived of water during its life.

The scan also revealed that the cobra's skull had been partially crushed and its vertebrae broken. Johnston thinks the snake died after being whipped against a wall or floor.

"They used the snake like a bull whip," he said, adding, "the entire right hand side of its skull was damaged."

The researchers also found that the cobra's mouth had been purposefully wrapped in an open position, and its throat filled with a type of resin called natron.

Johnston said that the presence of natron indicated the snake possibly underwent an "Opening of the Mouth"ceremony - a burial ritual that allowed the mummy to eat, breathe, and enjoy offerings in the afterlife.

"It elevates the animal," he added.

Without the new technique, the team wouldn't have found the natron. They also wouldn't have been able to identify the species that the second mummy, a bird, belonged to.

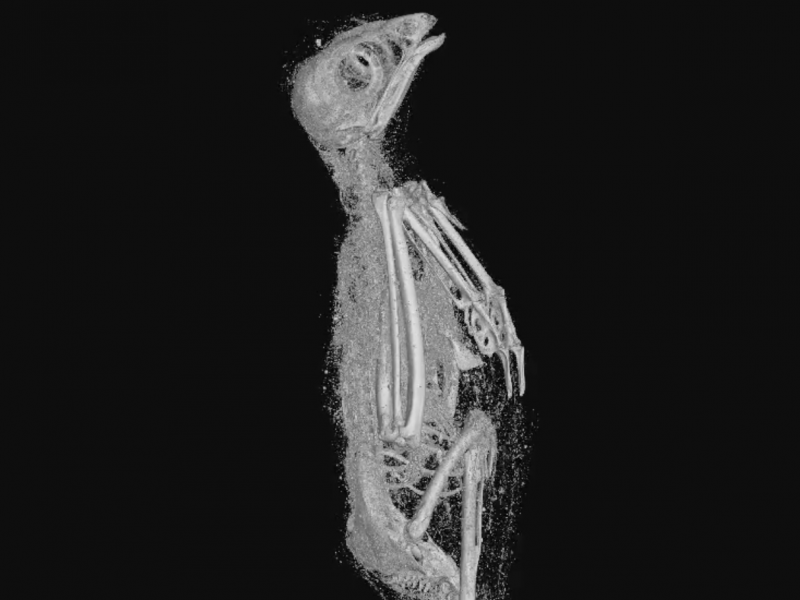

The researchers identified this mummy as a Eurasian kestrel, a bird of prey.

The scan's high resolution (it's about 100 times more precise than a medical CAT scan) helped them measure the kestrel's bones.

They weren't able to discern how the kestrel died, but confirmed that the animal didn't die from a neck injury like the snake.

The final mummy, which Johnston's group identified as a domestic cat, likely did die from neck trauma, however.

The cat's neck vertebrae had been violently separated, which could indicate the animal was strangled, he said.

It's also possible the Egyptians broke the cat's neck after it died so they could mummify it with its head in an upright position.

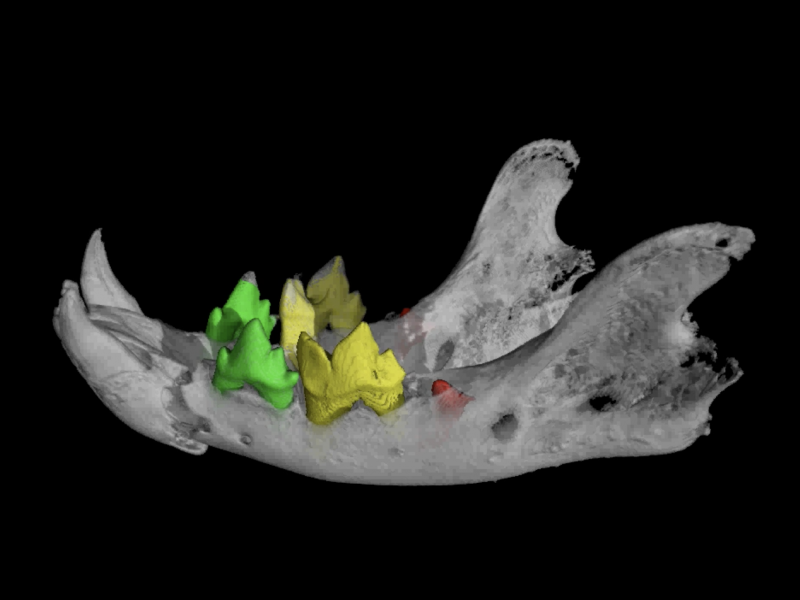

The micro-CT scan enabled Johnston to see the cat's remains in unprecedented detail, even down to its teeth.

An analysis of the teeth revealed the cat was actually a 5-month-old kitten.

Johnston said this type of imaging is a breakthrough, since it's "non-destructive" to the animal skeleton.

"In the past, when people unwrapped mummies, everything inside moved around," he said, adding, "it would be difficult to put the skeleton back together in the position it was mummified in."

What's more, micro-CT scanning enabled the researchers to create 3D models of the animal mummies for analysis.

"I made one of the specimens as large as my house and wandered through it, looking for something new each time," Johnston said.

He next hopes to scan a mummified ibis — a type of bird Egyptians worshipped as sacred — and perhaps a crocodile, too.

But the technique works best on small objects, Johnston said. The bigger the mummy, the lower the resolution of each micro-CT image.

That's why the micro-CT technique doesn't work on human mummies: They're too large to fit into the scanning machine.

Still, researchers have previously used Johnston's technique to examine a severed hand or human head, he said.