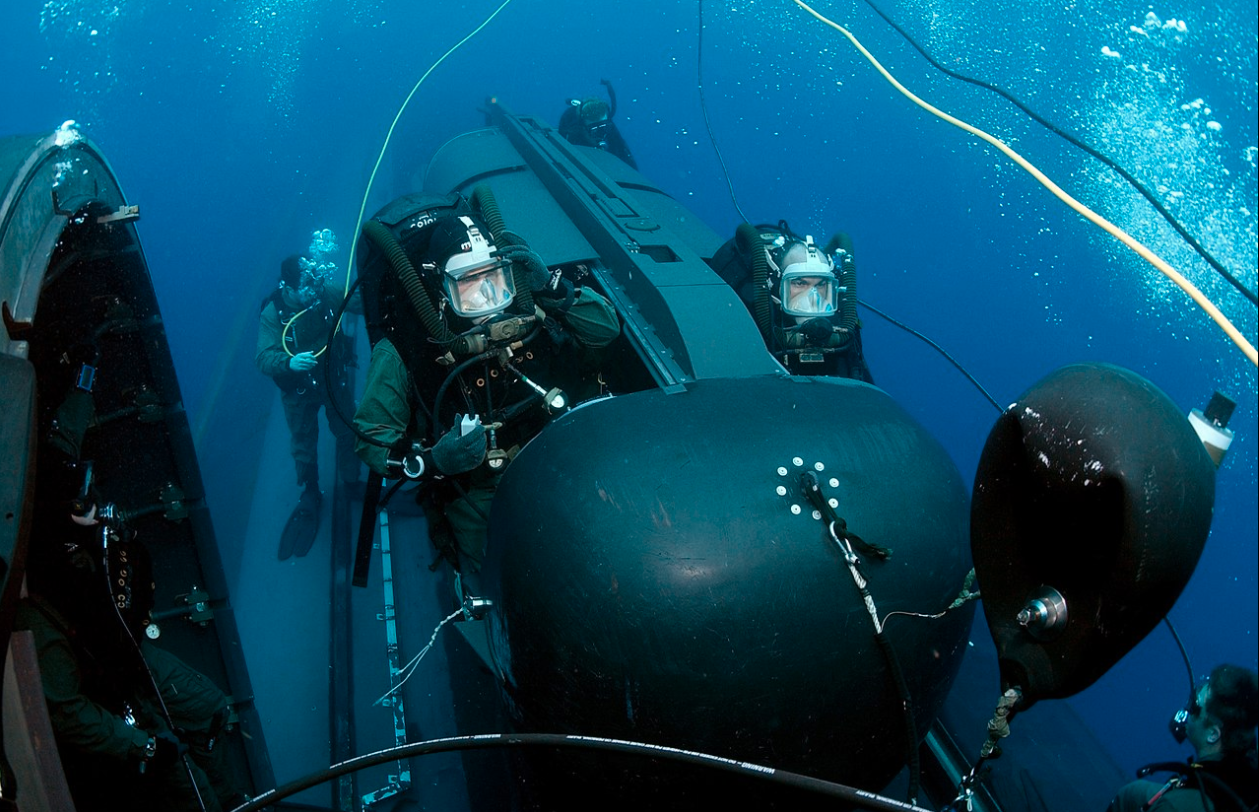

U.S. Navy photo by Senior Chief Mass Communication Specialist Jayme Pastoric

- Special-operations units from each US military service branch train to conduct combat diving as a part of their missions.

- Navy SEALs take that capability further, however, practicing not only to travel through the water but to conduct underwater missions as well.

- With the military refocusing for a potential conflict in the vast Pacific region, that diving capability is taking on new importance.

- Visit Business Insider’s homepage for more stories.

Water covers more than 70% of the earth, making maritime operations a must-have capability for any competent military.

Besides having the strongest Navy in the world, the US military possesses potent maritime special-operations resources, with the majority of its special-operations units having some combat diving capability.

Marine Raiders and Reconnaissance Marines have different training pipelines but go through the same dive school in Panama City.

US Marine Corps/Cpl. Savannah Mesimer

Army Green Berets have dedicated combat diver teams, and some Rangers go through the arduous Special Forces Underwater Operations School in Key West, Florida, one of the most challenging courses in the Army, where even special operators wash out.

Air Force Combat Controllers, Pararescuemen, and Special Reconnaissance operators also go through dive school in Panama City before finishing their own training courses. Those units often send students to the Army’s course.

With some exceptions, such as Special Forces dive teams who teach combat diving to foreign troops, for these units combat diving is primarily an insertion method - a way to the job rather than the job itself.

However, Navy SEAL Teams take maritime special-operations to another level.

Frogmen

US Marine Corps

Navy SEALs trace their lineage to the Underwater Demolition Teams (UDT) of World War II.

These frogmen were tasked with amphibious reconnaissance and clearing beaches before the Marine Corps or the Army landed. They saw action in Normandy during D-Day and in almost every major operation in the Pacific.

Since then, the combat diver capability (or combat swimmer, as SEALs call it) is part of every SEAL's DNA. SEAL students receive combat diving training during the initial and the advanced portions of the SEAL pipeline.

Aspiring SEALs learn the basics of combat diving during the Second (or Dive) Phase of the six-month Basic Underwater Demolition/SEAL (BUD/S) training course. This portion of the training contains Pool Competence, the pipeline's second most difficult event after First Phase's Hell Week.

During Pool Comp, students go through increasingly stressful underwater tests in a monitored environment. The goal is to see if they can follow basic procedures that could save their lives in a real-world operation while under extreme physical and mental stress.

During the SEAL Qualification Training (SQT) course, which comes after BUD/S, aspiring SEALs receive additional and more advanced combat diving training.

US Navy/Senior Chief Mass Comm. Spec. Jayme Pastoric

The reason for the additional training is that SEALs are the only special-operations unit tasked with underwater special operations, such as placing limpet mines on enemy ships or conducting reconnaissance of an enemy harbor.

One of their better-known underwater missions took place in 1989 during Operation Just Cause. A four-man SEAL element was tasked with sinking Manuel Noriega's personal boat to prevent the Panamanian dictator's escape. Despite some resistance from a few vigilant guards, the SEALs were able to plant limpet mines and destroy the vessel.

Although the SEAL Teams' missions might be different than those of other US special-operations combat diver units, the basic training isn't.

"Actually, the military's combat diver communities are all very similar in the curriculums being taught," a highly seasoned Special Forces combat diver told Insider. "We all fall under SOCOM [US Special Operations Command], and the Navy is the proponent for all diving operations. They approve and monitor tasks being taught at each school."

"We all use [combat diving] for the same reason - clandestine infiltration using an oxygen rebreather," the operator said, referring to the MK25 MOD2, made by Dräger.

"[We all] get to work using our fins," added the operator, who has taught at the Army's combat diver school and at BUD/S.

A potential conflict in the Pacific is a reason for all services to maintain or even improve their combat diver capabilities. However, there is still a lot to be done on that front, especially for Army special-operations units, where the capability has been neglected to a dangerous extent.

Diving into the future

US Army

With the Pentagon focused on great-power competition, maritime special-operations are increasingly relevant and important, and that's where the SEAL Teams can shine.

"The Teams can do so much in conflict with China," a former SEAL officer told Insider. "We have the ability to conduct small unit surveillance and reconnaissance during over-the-beach ops; place sensors to aid intelligence gathering, again during over-the-beach ops; train foreign forces (for example, training the Taiwanese in all manner of stuff to balance Chinese capabilities); and also do direct action (an extreme example, but doable if so required)."

Unlike other special-operations units, in the SEAL Teams everyone is combat diver qualified. As a result, there is a vested interest in the capability, both from an operational and budgetary standpoint.

US Navy photo by Chief Photographer's Mate Andrew McKaskle

"Compared to other special-operations commands, NSW [Naval Special Warfare] as a whole will be more relevant in a great-power competition setting, at least in the Pacific, because of the maritime nature of the environment," a SEAL officer told insider. "We might see platoons diving but not to place a limpet mine on a Chinese warship but a sensor on a ship of interest."

Aside from traditional combat diving operations, the SEAL Teams also possess the SEAL Delivery Vehicle (SDV) capability.

There are two SDV Teams that are manned by SEALs who undergo even more combat diving training and operate the mini-submarines. Although much of their mission-set is classified, they are known to conduct special reconnaissance and stealthily transport SEALs closer to a target.

Stavros Atlamazoglou is a defense journalist specializing in special operations, a Hellenic Army veteran (National Service with the 575th Marine Battalion and Army HQ), and a Johns Hopkins University graduate.