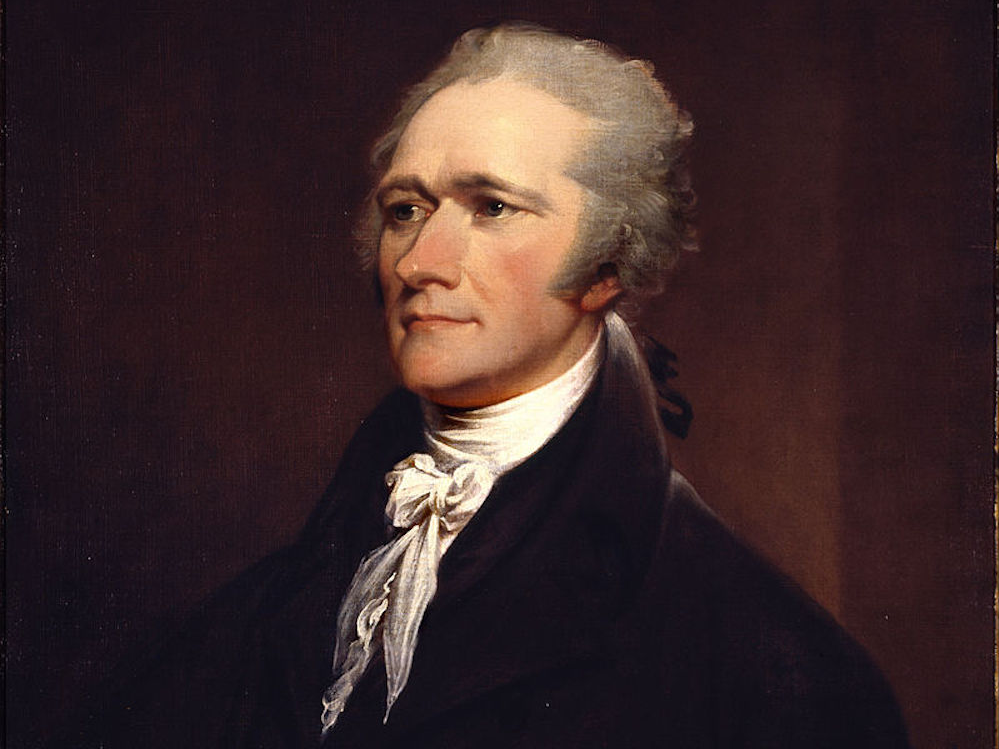

- Alexander Hamilton was the first Treasury Secretary of the US.

- He also spearheaded promoting the US Constitution and founded the national’s financial system, the US Coast Guard, and The New York Post.

- Take a look at some of the habits and strategies that helped Hamilton remain productive throughout his career.

Alexander Hamilton was a pretty busy guy.

Heck, the whole song “Non-Stop” in Lin-Manuel Miranda’s smash Broadway hit “Hamilton” is dedicated to the man’s meteoric rise from orphaned Nevis immigrant to aide-de-camp to George Washington to full-fledged Founding Father.

Hamilton had a tremendous influence on the development of the United States. Not only was he the first Treasury Secretary of the young country, he was also responsible for founding our financial system and ensuring the adoption of the US Constitution.

In his spare time, Hamilton kicked off the US Coast Guard, The New York Post, and the New York Manumission Society, which fought for the abolition of slavery in New York.

Here's a breakdown of what a day in the life of Alexander Hamilton might have looked like:

In a 1800 letter to his then-18-year-old son Philip — who would die in a duel three years before the famous Hamilton-Burr showdown of 1804— Hamilton extolled the benefits of rising early.

Source: The Founders Archives

He advised Philip to wake up no later than 6 a.m. from April to October, and no later than 7 a.m. for the rest of year. Hamilton added that his son would "deserve commendation" if he deigned to rise earlier.

Source: The Founders Archives

Given Hamilton's own intense work ethic, it's not a stretch to imagine that he himself also woke up relatively early.

Source: The Founders Archives

Unsurprisingly, Hamilton reportedly relied on lots of java to ease into the day.

Source: NPR, Dinner at Mr. Jefferson's: Three Men, Five Great Wines, and the Evening That Changed America, Cal Newport

Hamilton's friend William Sullivan wrote that he typically slept for six or seven hours, and preferred to drink "strong coffee" in the morning.

Source: NPR, Dinner at Mr. Jefferson's: Three Men, Five Great Wines, and the Evening That Changed America, Cal Newport

Hamilton recommended that Philip dress, eat breakfast, and then study law until 9 a.m. After that, the schedule called for the younger Hamilton to head to the office, where he would read and write law.

Source: The Founders Archives

Dinnertime in the Hamilton household occurred in the middle of the day. Hamilton's favorite dishes are lost to history, but author Laura Kumin has speculated that the founder's wife Eliza would have likely brought Dutch-influenced tastes in their home.

Source: NPR, "Dinner at Mr. Jefferson's: Three Men, Five Great Wines, and the Evening That Changed America," "The Hamilton Cookbook: Cooking, Eating, and Entertaining in Hamilton's World," The Founders Archives

That meant meals like "hearty split pea soup served with rye bread, topped with Dutch-style smoked bacon," according to NPR.

Source: NPR, "Dinner at Mr. Jefferson's: Three Men, Five Great Wines, and the Evening That Changed America," "The Hamilton Cookbook: Cooking, Eating, and Entertaining in Hamilton's World"

Hamilton also had a sweet tooth. This was made especially clear during the Founding Father's fateful 1790 dinner with Thomas Jefferson and James Madison — during which it was decided that the US capital would be moved to the banks of the Potomac, in exchange for a national bank.

Source: NPR, Dinner at Mr. Jefferson's: Three Men, Five Great Wines, and the Evening That Changed America

Hamilton was apparently particularly taken with the dessert served by Jefferson: vanilla ice cream "enclosed in a warm pastry, like a cream puff." The founder "positively exulted" the dish, according to historian Charles Cerami.

Source: NPR, Dinner at Mr. Jefferson's: Three Men, Five Great Wines, and the Evening That Changed America

The Hamiltons also reportedly introduced George and Martha Washington to the joys of ice cream in 1789.

Source: "Ice Cream," NPR, "Dinner at Mr. Jefferson's: Three Men, Five Great Wines, and the Evening That Changed America," "The Hamilton Cookbook: Cooking, Eating, and Entertaining in Hamilton's World"

One thing that Hamilton allegedly wasn't skilled at was holding his liquor. John Adams — who was no fan of Hamilton by any means — called his fellow founder an "insolent coxcomb who rarely dined in good company where there was good wine without getting silly and vaporing about his administration, like a young girl about her brilliants and trinkets."

Source: "Alexander Hamilton," NPR, Dinner at Mr. Jefferson's: Three Men, Five Great Wines, and the Evening That Changed America

After partaking in the main meal of the day, Hamilton told his son to continue to read law until 5 p.m., after which he could take a break and spend "his time as he pleases." At 7 p.m., the eldest Hamilton child could read and study "whatever he pleases," before heading to bed.

Source: The Founders Archives

Of course, Hamilton was breaking down this schedule for a young law student. But the rigorous routine reflects how the Founding Father was able to plan his own time in order to achieve maximum productivity. This is, after all, the man who wrote 51 of the 85 Federalist Papers in the span of just eight months.

Source: The Founders Archives, "Alexander Hamilton,"

Hamilton biographer Ron Chernow wrote that, whatever he was doing, the founder "approached this daily routine with the same perfectionist ardor that he exhibited in his studies." His good friend Robert Troup, who observed Hamilton at the start of his career in the Continental Army, praised his "military spirit" and added that he was "very ambitious of improvement" in life.

Source: The New York Times, "Alexander Hamilton,"

Sullivan wrote that Hamilton would sit at his table and work in stretches of "six, seven, or eight hours" at a time. "Hamilton developed ingenious ways to wring words from himself," Chernow wrote. "One method was to walk the floor as he formed sentences in his head." Chernow attributed to his "tremendous output" to a combination of "superhuman stamina and intellect" and a propensity for "a fair degree of repetition."

Source: "Alexander Hamilton"