Tech giants are starting to turn their attention to “flying cars.”

Uber released a 98-page white paper last week outlining its plans to bring “flying cars” to commuters by 2026. Google co-founder Larry Page is also funding a “flying car” project through a start-up named Zee.Aero, and its prototype was reportedly seen in action at Hollister Municipal Airport in October.

But Airbus, which offers a legacy of building civil aircrafts and working with the Federal Aviation Administration, is also developing its own “flying car” as part of its Project Vahana – and its aviation experience could give it an edge. Project Vahana is being run under Airbus’ Silicon Valley arm, named A³.

To get this out of the way early, all of these companies aren’t really interested in developing flying cars, hence the quotation marks. That would indicate they were trying to take the same route as Terrafugia, which is building a hybrid car that can drive on the road and also fly.

But A³, along with Uber and what we know of Zee.Aero, isn’t focused on the car portion of a flying car. All three are working on VTOL aircrafts, which is short for Vertical Take-Off and Landing. That means the aircrafts don’t need a runway to ascend, similar to a helicopter.

Zach Lovering, who oversees Project Vahana, said it plans to have the production version of its VTOL aircraft ready in four years.

The Project Vahana aircraft will be an electric, single-passenger VTOL plane with eight rotors. Lovering told Business Insider it will have a range "on the order of a city size, the diameter of a city," but declined to provide a specific number. It will have a speed "twice as fast as cars" and will achieve an altitude of around 1,000 feet, according to Lovering.

The aircraft will be fully self-piloted.

"The way I would think about it is somewhat like a train... which means before it takes off it has a known flight path it's going on." Lovering said.

He said the aircraft will be equipped with lidar, radar, and cameras - the same technology used on many self-driving cars - so it can safely deviate from its flight path if an obstacle gets in its way.

Lovering joined Project Vahana in February after spending four years working for Page's Zee.Aero.

"There's a much bigger focus here on actual productization and getting this thing out there, rather than focusing on developing really cool technology," Lovering said of his decision to leave Zee.Aero.

But why pursue a VTOL aircraft?

Lovering said he can see many uses for these types of transport systems, but that Project Vahana is primarily going after the commuter market.

Lovering said he wants to create a ride-hailing experience that's "something like Uber has." Here's how he sees it playing out: the vehicles will have home bases on the top of buildings, such as large parking structures. Users will put where they are and where they want to go into a Project Vahana app, which will then direct them to the nearest depot with the aircrafts.

"You either take an Uber there or walk there, depending on how far away it is," Lovering said.

Once a user gets in the VTOL aircraft, pre-flight checks would commence. Lovering said relevant information about the flight will be displayed on the app, and there may even be a screen inside the aircraft that could "hook up to your phone, just as a casting device." None of these details have been finalized, but speak to the ride-hailing interface Lovering hopes to create.

Uber is also looking to use the VTOL aircraft for commuter purposes as part of its project dubbed Uber Elevate. Uber is planning to have its first vehicles ready by 2021, just one year after Project Vahana plans to finish its aircrafts. Uber has said its official roll-out date will occur in 2026.

Lovering added that Project Vahana's aircrafts could also be used to transport cargo from from facilities to distribution centers. They could also be used to deploy emergency medical stations in disaster areas.

'Huge regulatory hurdles'

But Project Vahana's vision for its VTOL aircrafts hinge on the FAA granting regulatory approval, and that's a big hurdle considering the FAA has yet to even approve commercial drone use.

"The regulatory aspects are definitely something difficult to overcome," Lovering said. "Although in our conversations with the FAA, we met with them earlier this year, they were very receptive to us."

Lovering said the FAA is moving toward a standard certification process that would expedite the process for approving new kinds of vehicles.

He added that there are organizations working with the FAA to help set these standards, like ASTM International, a volunteer organization that helps develop international standards; the Radio Technical Commission for Aeronautics, a volunteer organization that develops technical guidance for the industry and is sponsored by the FAA; and GAMA, an aviation industry trade association.

The FAA did not respond to Business Insider's request for comment.

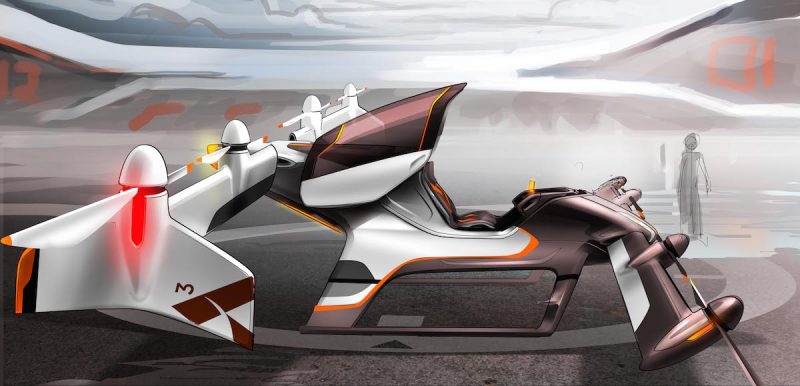

(Above: A VTOL aircraft built by Lockheed Martin.)

"It seemed like there were some clear paths forward for the regulatory environment as long as you have a pretty well-defined mission," Lovering said of his conversation with the FAA earlier this year.

But there are other hurdles beyond tackling the difficult regulatory environment.

Lovering said A³ needs to figure out how to build an "air infrastructure" so the aircrafts can fly safely. The group also needs to set up charging stations at landing sites since the aircraft will be electric.

Lovering said it will be important to partner with other companies working on VTOL aircrafts to work out these challenges. He said he could see A³ working with Uber down the road for that very reason.

"There are just huge regulatory hurdles, air traffic management hurdles, structural hurdles," he said. "That certainly will require not just Airbus and one other company, but probably half a dozen to a dozen companies working together to solve this problem."