- Thousands of migrants from Africa, Haiti, and Cuba are living in the southern Mexican border city of Tapachula, many in dire humanitarian conditions

- The migrants have passed through as many as eight countries to get to the border, but the Mexican government is denying them transit visas, preventing them from moving on.

- Around 3,000 people have formed the Assembly of African Migrants in Tapachula to demand transit visas and humanitarian assistance.

- Insider spoke to a mother of seven who fled gang violence from her home in Angola. She says she and most African migrants want to cross the continent and seek asylum in Canada, not the US.

- “I want to go to Canada, I believe we could be free there,” she said. “My children could have a better life, and I can go back to my work as an activist for women’s rights.”

- Visit Insider’s homepage for more stories.

TAPACHULA, Mexico – Theresa Ocampo had just seen the news story on her phone. President Trump visited the US-Mexico border to tout his relationship with Mexican President Andrés Manuel López Obrador. Together, Trump said, they were putting a stop to migrants flowing through Mexico.

“The situation for us is really getting more complicated,” she said with a grimace.

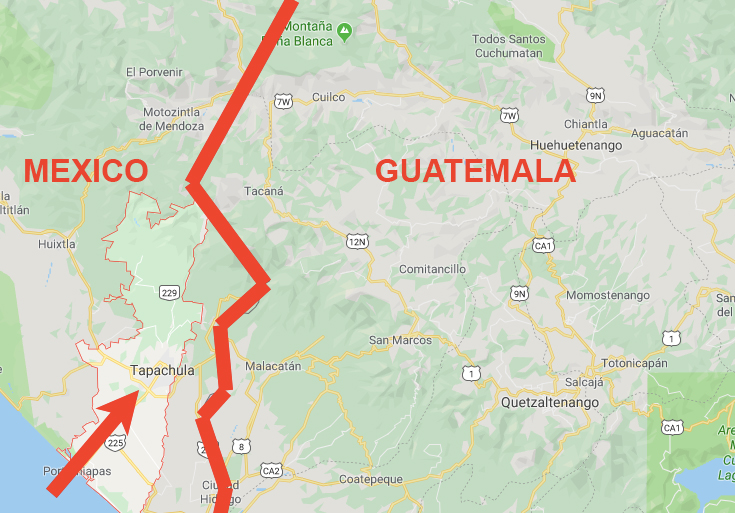

Theresa is one of the more recent residents of Nueva Esperanza – a village that has grown three or four times in size as migrants from Haiti, Cuba, the Dominican Republic, and several countries in Africa – began to arrive in the city of Tapachula after crossing the Guatemala-Mexico border.

Most of the occupants of this peripheral urban zone are fleeing war and persecution in their home countries, which include Burkina Faso, Cameroon, Mali, Sierra Leone, and the Republic of Congo. People call out to each other in French, Creole, Spanish, Portuguese, and English.

Fleeing her home country - and her adopted city

Theresa's journey began in her home city of Luanda, Angola. She was targeted by authorities for her women's rights activism and fled with her husband and children to Brazil, where they lived for six years in the megacity of São Paulo.

As gang violence began escalating in their neighborhood, Theresa decided it was time to move again, this time past the US border where neither governments nor gangs could get them.

With six children in tow - the youngest 18 months old - Theresa walked, and bused, and walked again: through Bolivia, Peru, Ecuador, Colombia, Panama, Costa Rica, Nicaragua, and Guatemala. She arrived at Mexico's southern border in June of this year.

And now she's stuck. The immigration authorities have designated many of the African migrants "stateless" and refused their applications for short-term "humanitarian visas," which would allow them to transit through Mexico without being detained or deported. Many were told that they must leave Mexico and travel back over the Guatemala border.

Theresa - a pseudonym we are using to protect her safety - is among the hundreds of other migrants who are holding out for the transit visas. They say they have the right to pass through Mexico in their quest for safety and security elsewhere and accuse Mexican immigration personnel of making grave mistakes in processing their initial applications.

As Mexico cracks down, African migrants are organizing

In early August, with the assistance of the local Fray Matias Centre for Human Rights, 3,000 African migrants from across Tapachula formed the Assembly of African Migrants.

In a demonstration on August 29, the Assembly demanded that the Mexican government issue the transit visas, expedite applications for refugee status for those who wish to claim it in Mexico, provide urgent humanitarian assistance, and ensure protection from Mexican security forces.

The Mexican government refused to oblige.

"We will not budge," Mexican president Obrador said in response to the protest. "The recent events in Tapachula aim to make Mexico yield and oblige us to give out certificates so migrants can get into the United States. We cannot do that. It isn't our job."

Critics said that Obrador was simply parroting language he'd adopted from Trump to appease the US government and ease tariffs the US had placed on Mexico, according to PBS.

In response to the protests, Obrador deployed Mexico's National Guard to crack down on the migrants, just as he promised to Trump. They surround the camp in front of the Siglo XXI immigration complex along with a military police troupe.

But while skirmishes with the military outfits have led to violence and injury during demonstrations, the migrants are most vocal about the staff at the Mexican immigration department. These are the bureaucrats in shirts sewn with the immigration department logo. They can sometimes be seen cutting a path through the tents to get into their offices, where protesters have emblazoned the walls with graffiti that says "Free the migrants" and "Mafia."

The Assembly has accused Mexican immigration authorities of tricking them when they asked to apply for transit visas and giving migrants documents that led them to be arrested.

"They made us sign documents that we did not understand. They gave us a document talking about our alleged statelessness, and tricked us by telling us that with that document we could travel without being arrested," the group said in a press release. "Those of us who tried [to travel], were detained again and returned to Tapachula. We were told that we could access a Visa for Humanitarian Reasons, but we were finally denied."

Read more: 'El Chapo' Guzman says his drug money should go back to Mexico, and Mexico's president agrees

In response to the protests, the UNHCR has created a new registration center for migrants in Tapachula that will be managed by the Mexican government's refugee assistance commission. The commission has said it "will enable asylum applications to be dealt with 'promptly and fairly.'"

"I'm a Christian, I have to have faith"

Although most of the migrants are living on donations and there is very little money in circulation, the newcomers have brought plenty of commercial and community activity to Nueva Esperanza. In an extension of the village's shanties and tin sheds, the forecourt of the immigration station is now covered in tents and tarpaulins, with clothes drying on railings and smoke rising from cookers made from old tins of baby formula. Makeshift barbershops, beauty salons, restaurants, and cafes have sprung up on the main roadside that leads up to the immigration offices.

Wilmer, a Haitian man who crossed into Tapachula in March, started his African restaurant a couple of months ago. He cooks up rice, beans, chicken, eggs, and spaghetti for around 40 pesos a dish that customers can pay at the time, or later.

"I'm here doing this every day," Wilmer told Insider, laying down a plate of chicken and rice for a hungry traveler.

"I'm a Christian, I have to have faith," he said. "Still, I think immigration is being very unfair. They have made us their captives."

Theresa agreed. As children get sick, and pregnant and women try to stay cool in the powerful tropical heat, she said the situation is deteriorating further and further.

"They're killing us slowly," she said.

Enrique Vidal, a coordinator at the Fray Matias Human Rights Center, said that the "bottleneck" of migrants stuck in Tapachula with few resources is part of the same phenomenon that forces migrants to remain in northern border cities like Tijuana under the Remain in Mexico policy.

"It's deliberate" added Vidal, referring to Mexico's ongoing co-operation with President Trump. "The Mexican government has agreed with the US government to repress migration."

But Theresa believes the US and Mexican governments are mistaken about the intentions of people like her and her family.

"They think we want to travel north so we can try and live in the United States. But ask any of the Africans here - we want to seek asylum in Canada," she said.

"We know they don't want us in the US. Trump is closing the border and there's racism against black people there," she continued. "I want to go to Canada, I believe we could be free there. My children could have a better life, and I can go back to my work as an activist for women's rights."

- Read more:

- Trump's new immigration bill is 'dead on arrival' - but its real value could be shoring up his immigration strategy for 2020

- Canada's minister of immigration explains what successful immigration policies look like

- Mexico's president called off a White House visit after Trump refused to say publicly that Mexico won't pay for the border wall

- THE OTHER BORDER 'CRISIS': While America is fixated on Mexico and the wall, thousands of migrants are fleeing for Canada in a dramatically different scene