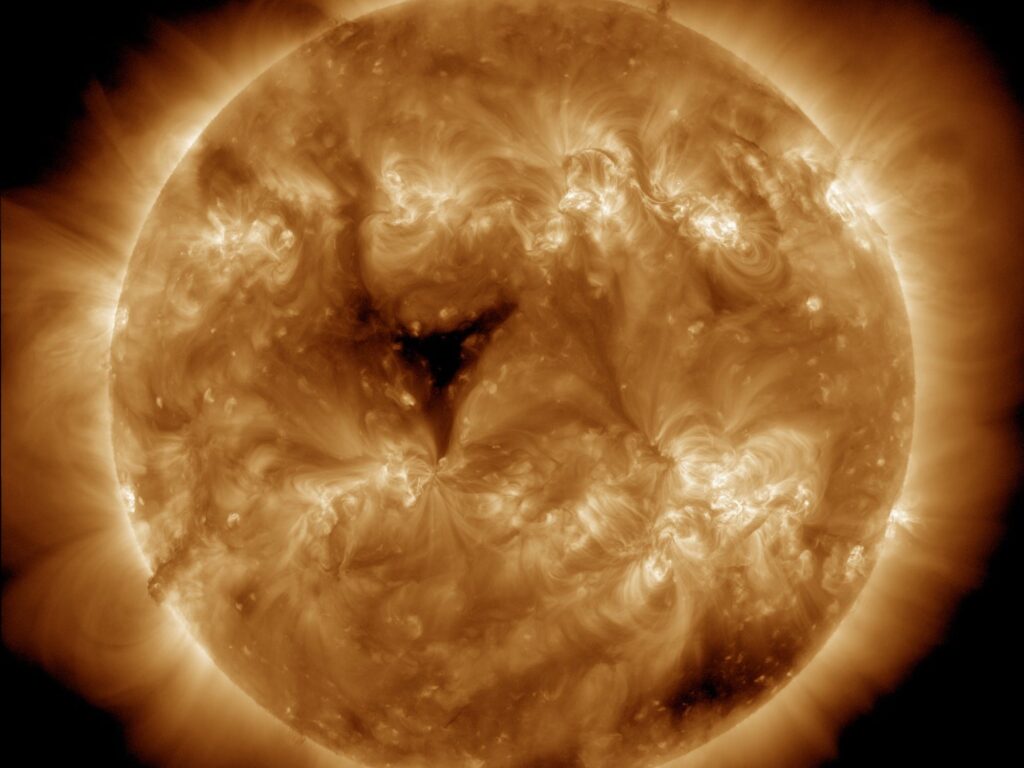

- A coronal hole on the sun, about 20 Earths across, has been spotted.

- These 'holes' can send 1.8 million mph solar winds towards Earth.

- The winds should hit our planet Friday or Saturday and could create auroras, experts said.

A giant "hole" has appeared on the surface of the sun and it could send 1.8 million mph solar winds toward Earth by Friday.

It follows the discovery of a coronal hole on the sun 30 times the size of Earth. As this first 'hole' begins rotating away from us, a new giant coronal hole — about 18 to 20 Earths' across — has come into view.

Coronal holes release solar winds into space which can damage satellites and reveal stunning auroras if they reach the Earth.

Scientists aren't concerned about this particular hole damaging infrastructure, although they say it may help trigger auroras in some parts of the world. Here's why.

The 'hole' is positioned close to the sun's equator

Coronal holes are fairly common, but they usually appear towards the poles of the sun, where their winds are spewed into space.

But as the sun is gearing up to a peak of activity, which happens about every 11 years, these holes are more likely to appear near the equator of the sun, said Mathew Owens, a professor of space physics at the University of Reading.

"This one being at the equator means we're pretty much guaranteed to see some fast wind at Earth a couple of days after it rotates past central meridian," he told Insider.

The solar winds can blast very fast solar winds, with speeds of more than 800 kilometers per second, Verscharen said. That's about 1.8 million miles per hour.

"The shape of this coronal hole is not particularly special. However, its location makes it very interesting," Daniel Verscharen, associate professor of space and climate physics at University College London, told Insider.

"I would expect some fast wind from that coronal hole to come to Earth around Friday night into Saturday morning of this week," he said.

Coronal holes allow solar winds to escape the sun more readily

The sun is a big ball of plasma. That plasma churns from the inside of the sun to its surface, and as it does, it creates magnetic fields that ebb and swell, crash and merge.

A coronal hole appears when those magnetic fields shoot straight up into space, per NASA. That makes it a lot easier for solar winds — bits of plasma from the sun — to escape into space at high speed.

Those areas are generally cooler and less dense than the surrounding hot, churning plasma, which explains why they show up as darker splotches on pictures of the sun.

If those magnetic lines are facing toward the Earth, that wind will come crashing into our atmosphere.

"If it is oriented in the southward direction, we're more likely to have a space-weather event, but we don't know that yet," Verscharen told Insider.

Auroras may get brighter — but not as bright as last week's

As these winds interact with our charged atmosphere, they can make auroras brighter. But don't expect to see them down in Florida.

When the skies lit up last week with brilliant auroras that were spotted as far south as Arizona, it wasn't only due to the coronal hole.

It just so happens that several coronal mass ejections (CMEs) — huge eruptions of plasma being thrown into space — happened around the same time as the hole was facing Earth, creating a huge geomagnetic storm, which is why the effect was so strong.

In the case of this coronal hole, it's unlikely this will happen again, experts said. This is a shame for fans of auroras, but it's probably good news for planetary defense, as strong geomagnetic storms can wreak havoc on satellites, infrastructure, and radio signals.

"I doubt it will result in too much excitement. Unless we just so happen to get an Earth-directed CME around the same time," said Owens.

Still, it's always difficult to predict space weather accurately.

"We are really behind with our prediction and forecasting capabilities for space weather," said Verscharen.

"That's why we're working very hard to understand space weather with the help of theoretical physics, plasma simulations on supercomputers, and cutting-edge observations with the latest spacecraft such as the joint ESA-NASA mission Solar Orbiter."